Millennials Banking On Cash Over Stocks For Retirement

Retirement might seem a long way off to the under-30 set, but, according to a new Bankrate.com survey, it’ll take many young adults even longer to get there, given how they’re investing.

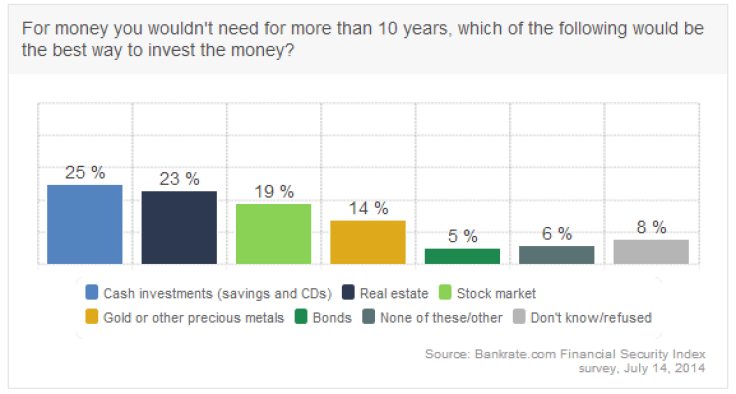

The latest Financial Security Index, a telephone survey of 1,000 adults in the United States, found respondents across the board preferred cash to any other investment vehicle. When it comes to “money you wouldn’t need for more than 10 years,” 25 percent said they’d choose to invest in savings and CDs, compared to 23 percent who selected real estate and 19 percent who opted for the stock market.

Yet of any age group, it was the young adults surveyed (ages 18 to 29) who showed the greatest affinity for cash: 39 percent said cash is the best investment versus 13 percent who preferred stocks on a 10-plus-year horizon.

“People of all ages -- but especially those under 30 -- are very risk adverse, particularly with money that isn’t going to be needed for a long period of time,” Bankrate.com chief financial analyst Greg McBride said.

In May, William Finnegan, a senior managing director at MFS Investment Management in Boston, told Bloomberg News: “We call them recession babies. If the cumulative return of the past five years didn’t convince you that the stock market might be an OK place to be for a long-term investor, I’m not sure what else is going to. These folks have been scarred.”

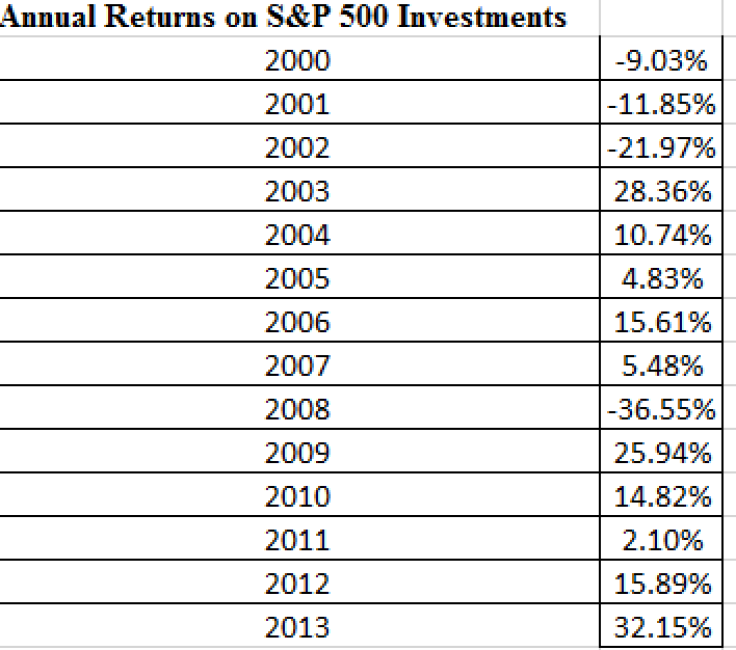

Maybe it's because the group has been looking at the longer-term market performance.

Their brief history includes three years of increasing stock losses in the early 2000s with a slow but steady recovery in the following years and topped off by the nauseating 37 percent crash in 2008 at the height of the financial crisis.

The problem with that, McBride said, is what happens when Millennials, facing longer life expectancy and rising health care costs, eventually want to exit the workforce -- minus the pensions their parents have enjoyed.

“The burden on them to save for their retirement is greater than any other generation has faced,” McBride said. “They’re not going to get there by investing in cash.”

Finnegan's report concluded: "The data confirm that we have a lost generation of investors. The impact of 2008's Great Recession has had a deep-seated secular impact on millennial investors. Their grandparents are more aggressive investors."

Given what millennials saw growing up, is it surprising they don't trust the market?

When building a nest egg, the “power of compounding” higher returns is what really adds up, McBride said. And if millennials want to reap the long-term benefits, he added, they’ll have to learn “to bear some short-term price risk” in the markets.

For millennials though, looking back at the S&P 500 and seeing four years of steep losses out of the last 14 years, it's not hard to understand why last October more than half of 1,500 polled said they were, ”not very" or "not at all" confident investing for retirement in the stock market.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.