Minimum Wage In Washington: After 16 Years, State With Highest Minimum Wage Maintains Lower Unemployment Than National, Regional Averages.

Would raising the federal minimum wage be the job-killing apocalypse opponents predict? Perhaps the answer to that question lies in Washington state's unemployment metrics.

The home of Microsoft and Amazon.com has had the nation’s highest state minimum wage for years, ever since voters there passed Initiative 688 in 1998, which raised the hourly wage floor over two years to $6.70 an hour and linked future increases to the consumer price index for urban clerical workers. Today, the wage floor for most of Washington’s hourly workers remains the highest of any state at $9.32 an hour.

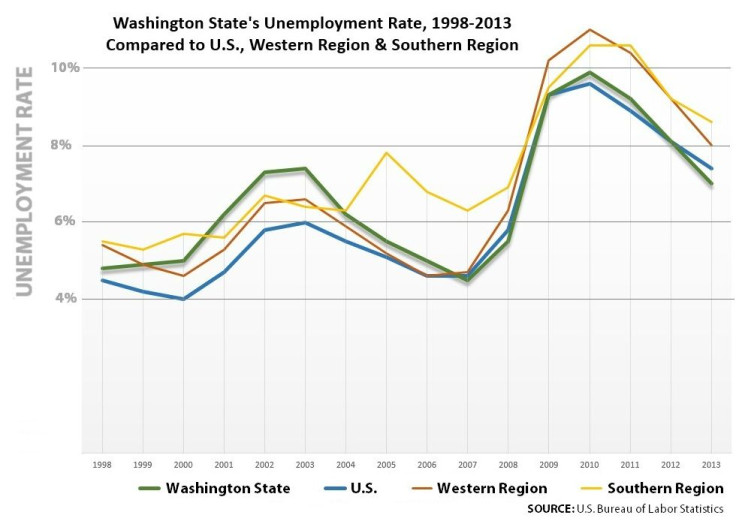

As the nation embarks on its cyclical national debate (the last time was in 2006) on adjusting the federal minimum wage, how has Washington fared? Here’s a snapshot of the state’s unemployment rate compared to the U.S. national average, the 13 states of the Western Region (including Hawaii and Alaska) and the 17 states of the Southern Region.

These numbers suggest an initial unemployment shock between 2000 and 2003, followed by a gradual reduction.

Meanwhile, the average annualized jobless rate in the Southern Region spiked in 2004 and remained well above the national average until the bank-caused sub-prime mortgage meltdown sent the national jobless rate shooting higher.

Nine Western Region (and five cities) currently have minimum wages well above the federally mandated $7.25 an hour. Among the Southern Region states, only Florida and D.C. have minimum wages above $7.25 an hour.

Also, as Bloomberg reported on Wednesday, Washington’s job growth is 0.8 percent annually, outpacing the national average of 0.3 percent. Since 1999, Washington’s restaurants and bars have expanded their payrolls by 21 percent, too.

After 16 years of having one of the country’s most progressive minimum wage policies, Washington’s unemployment rate has been below the national average for four of the past five years, and well below the two regions. And despite the uptick in unemplyment in the years after the wage floor was raised, jobless figures for the state now has a jobless rate that's lower than the national average.

Roland Zullo, labor economics researcher at the University of Michigan, explains what might have happened:

“Imagine how a firm would behave [when a high wage is mandated by the state],” he told International Business Times. “If you own a burger joint and you’re initially hit with a higher wage bill, maybe that forces you to find a way to get by with fewer people. But then later in the surrounding economy — because everyone at that wage level is getting paid more – you then have more customers. That in turn forces you to hire more labor back. Having customers is as important if not more important than the wage you’re paying your workers.”

So why the controversy? Why are so many groups, including the restaurant-industry-lobbyist-backed Employment Policies Institute, arguing the apocalypse if the wage floor is raised to $10.10 an hour, as the White House is advocating, or $15 an hour for fast food workers, as demanded by some labor rights groups?

Part of has to do with fighting any measure that raises costs to employers, who have a responsibility to themselves (and to their shareholders in the case of listed comapnies that utilize large pools of hourly wage workers) to oppose any government policy that increases company operating expenses.

But another has to do with dueling economic ideologies.

On one side are the classical economists. You know them by their frequent use of Economics 101 supply-demand charts (there are many). They argue that the wage floor lowers demand for labor and therefore costs jobs. The line chart above suggests that Washington indeed saw an increase in unemployment at a faster rate than the national and regional averages in the first years after the 1999 wage mandate; but then there was a leveling-off and a steep decline in joblessness from 2004 to 2007.

Back in 1998, the classical economists decried Initiative 688 as a job killer.

“It would also put Washington in an unfavorable position when compared with nearby states that may compete for new economic growth,” said David A. McPherson, professor of economics and research director of the Pepper Institute on Aging and Public Policy at Florida State University, in a report in October 1998, during the debate over Initiative 688. “The largest negative impact would be job loss. There exists a rare and nearly unanimous consensus among economists that increasing the minimum wage causes unemployment.”

The other perspective on wage floors comes from the institutional economists who believe that a stable political system is necessary for economic growth, and that the more people cannot meet their economic needs the more unstable an economy (and ultimately, a country) becomes.

Wages that don't pay workers enough to afford shelter, food, education and health care also put more pressure on government spending. Wal-Mart Stores Inc. (NYSE:WMT) and McDonald’s Corp. (NYSE:MCD) have been slammed over the past year by labor unions and activists for paying many of their workers so little they need food stamps and other social welfare provisions, which act as taxpayer-funded income subsidies to company payroll expenses.

“Inequality taxes an economic system in numerous ways,” said Zullo.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.