Mobile Banking Market In Sub-Saharan Africa Could Be Worth $1.3B In Four Years

For many mobile phone users, sending and receiving money by phone is a faster way to pay for a morning coffee or shop online, but for millions in sub-Saharan Africa -- where many people don’t have access to traditional banks -- mobile money has potential to change lives and spur business development.

The mobile money market in sub-Saharan Africa was worth $655.8 million last year and could be worth as much as $1.3 billion by 2019, according to new data from U.S.-based marketing analysis firm Frost & Sullivan. But it’s not just a business opportunity. The boom could help connect millions of people with a formal banking system they wouldn’t have access to otherwise.

“Governments in sub-Saharan Africa have come to realize that mobile money is key to improving the region’s financial inclusion,” Frost & Sullivan analyst Lehlohonolo Mokenela said.

Using a mobile phone to send or receive money is more about convenience. For the region’s “unbanked” population, a lack of access to banking systems can perpetuate the cycle of poverty and discourages business development.

“Compared to other economies, many firms in Africa lack proper access to a bank line of credit -- a major obstacle for firm growth,” World Bank analysts wrote in a 2012 paper. In addition, other financing sources such as equity markets are underdeveloped.”

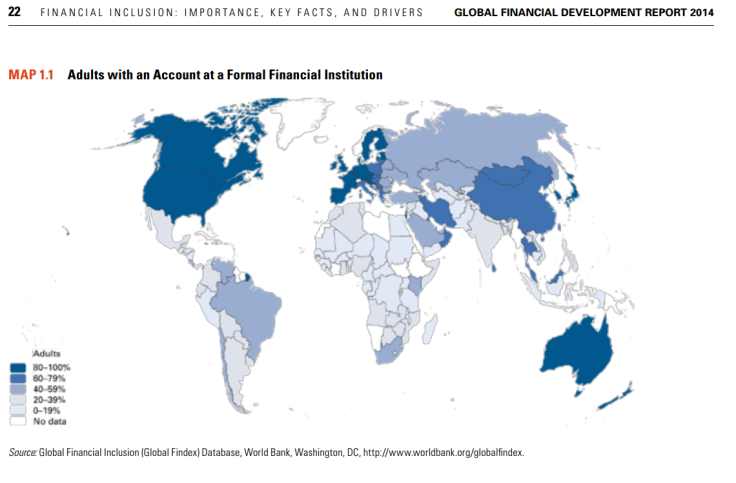

According to the Global Findex Inclusion Database, just 23 percent of adults living with less than $2 per day have an account at a financial institution, and they are more likely to use informal sources of credit, which can be as simple as borrowing from a family member or friend. Much of this population is in sub-Saharan Africa.

“One of the main reasons for this large unbanked population in Africa is geographical inaccessibility and poor infrastructure, with many of the unbanked living in remote rural areas,” analysts with iVeri Payment Technologies Ltd., a South African-based company that develops electronic payment technology solutions, said in a 2014 whitepaper.

“This, combined with the high cost of banking services and a lack of financial education and understanding, creates very high barriers to banking for poor rural populations.”

However, even in some of the most remote areas, most people have a cell phone.

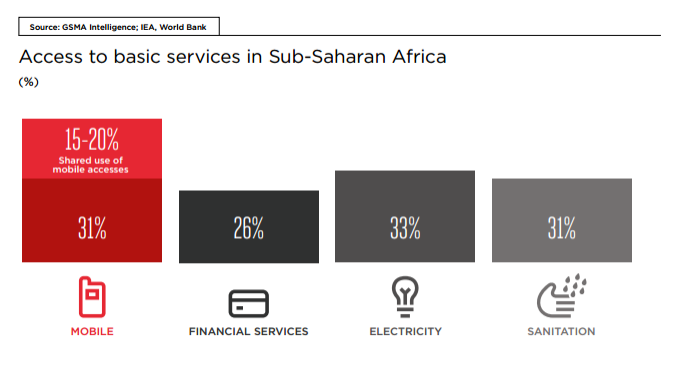

“In some of the least developed regions, such as parts of sub-Saharan Africa, there are much higher levels of mobile access compared to other basic service, such as electricity, sanitation and financial services,” according to trade association GSMA’s 2014 Mobile Economy report.

For example, in Nigeria 56 million people live without access to electricity, and 38 million live without access to clean water. But roughly 90 percent of the population has access to cell network coverage, which connects them to health, banking and other services through their cell phones.

But in sub-Saharan Africa, mobile banking has emerged as one of the key ways of fighting this problem, since even in the poorest or more remote regions, people are likely to have access to a cell phone.

In fact, more than 16 percent of people in the region say they use their phones to pay bills or receive money, compared to 3 percent worldwide, which is one way of fighting the problem of a large “unbanked” population.

According to the World Bank, a 10 percent increase in mobile broadband penetration translates, on average, to a 1.4 percent increase in gross domestic product.

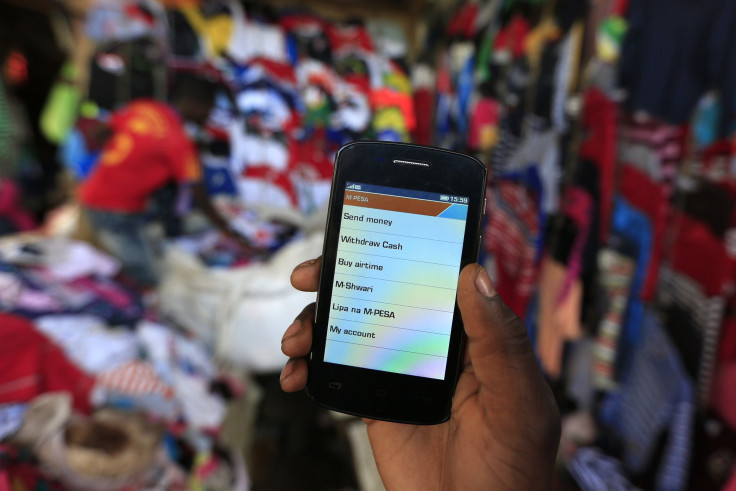

There are already a handful of providers facilitating this kind of service, which has caught on fast. In 2007, Kenyan telecom company Safaricom launched M-Pesa -- the M is for "mobile"; pesa is Swahili for "money" -- one of the first mobile money transfer services in the region. Today, it has more than 17 million customers, about two-thirds of the adult population, and roughly a quarter of Kenya’s gross domestic product flowed through it in 2013. The company's success inspired providers around the region to try and replicate the service, but it’s still a work in progress.

“As the market is still in a somewhat early stage of development, it is dominated by [mobile money transfers] between subscribers of the same operator,” Frost and Sullivan’s Mokenela said, noting that the majority of cell phone money transfer services are run by providers, and so would require a great deal of cooperation from each other and local governments to truly change the banking landscape.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.