Mollusk 'Missing Link' Fossil Unearthed

An ancient relic was buried deep underneath Great Britain for generations. Now, scientists that discovered the relic think it can answer profound questions about life.

The relic in question is not the Holy Grail, supposedly toted to Britain by Joseph of Arimathea – it’s the fossil of an ancient mollusk called Kulindroplax perissokomos, a tiny creature with a rounded body surmounted by a series of overlapping shells. (The name ‘Kulindroplax’ is derived from the Greek words for cylinder and plate).

“This is a kind of missing link with a worm-like body, bearing a series of shells like those of a chiton or coat-of-mail shell," Yale researcher Derek E. G. Briggs said in a statement.

Kulindroplax was unearthed about 10 years ago, but the fossil was identified as a new species only Wednesday, with the release of a paper from Briggs and his colleagues in the journal Nature.

The fossil itself is about 2 centimeters wide and 4 centimeters long, and was buried in a layer of volcanic ash amongst other traces of marine life in the rich Herefordshire fossil deposit.

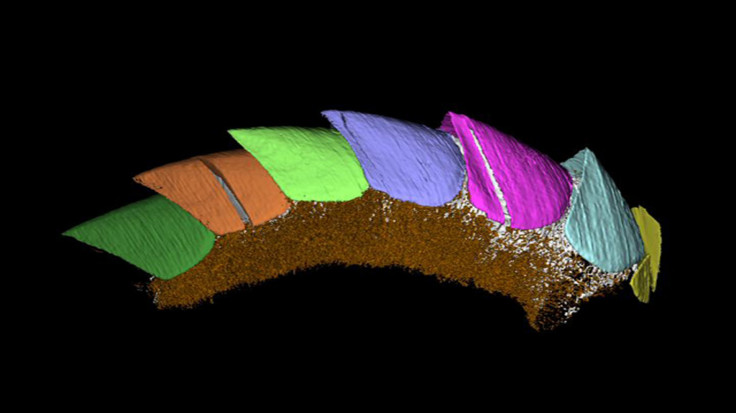

To create a model of the mollusk, researchers cut the fossil into 1,300 slices and took a digital picture of each piece. They then assembled the digital fossil slices on the computer to make a three-dimensional model of this invertebrate ‘missing link.’

Kulindroplax lived in the ocean about 425 million years ago during the Silurian period, a time when the hot new kind of animal on Earth was the newly evolved bony fish and when the only major life forms on land were moss-like plants. And it could be proof that simpler worm-like mollusks evolved from the more complex shelled kind, possibly closing the book on a long-standing debate among scientists.

Both the shell-less aplacophorans and the shelled chitons, also known as sea cradles, still exist today. Until recently, many scientists thought chitons arose from a more ancient lineage of aplacophorans.

But by carefully scrutinizing the features of Kulindroplax, the team thinks that aplacophorans actually evolved from chitons by shedding their shells.

"Most people don't realise that mollusks, which have been around for hundreds of millions of years, are an extremely rich and diverse branch of life on Earth,” lead author and Imperial College London researcher Mark Sutton said in a statement Wednesday.

“Just as tracing a long lost uncle is important for developing a more complete family tree, unearthing this extremely rare and ancient Kulindroplax fossil is helping us to understand the relationship between two mollusk groups, which is also helping us to understand how mollusks have evolved on Earth."

SOURCE: Sutton et al. “A Silurian armoured aplacophoran and implications for molluscan phylogeny.” Nature 490: 94-97, 4 October 2012.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.