Most Cars Have Confusing Child Restraint Hardware, From Buried Baby Seat Anchors To Tether Troubles

The German car companies have figured out how to make baby seats easy to install. Everyone else? Not so much, according to researchers who put 100 vehicles to the test in a first-ever comparison of design quality in automakers' baby-seat installation hardware.

“These first results are worrisome,” said Jessica Jermakian, senior research scientist for the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), a nongovernmental automotive testing group funded by auto insurers. The researchers said more than half of the cars had baby-seat installation hardware that was so difficult to use that parents might improperly install them or opt to secure the seats using just the safety belts.

The institute is concerned because parents are more likely to avoid using the systems of anchors and tethers to properly secure baby seats. If the seat isn’t secured properly, babies can be injured.

These Lower Anchors and Tethers for Children, or LATCH, systems have been required in all new cars in the U.S. since 2002; they’re safer than baby secured only by standard safety belts.

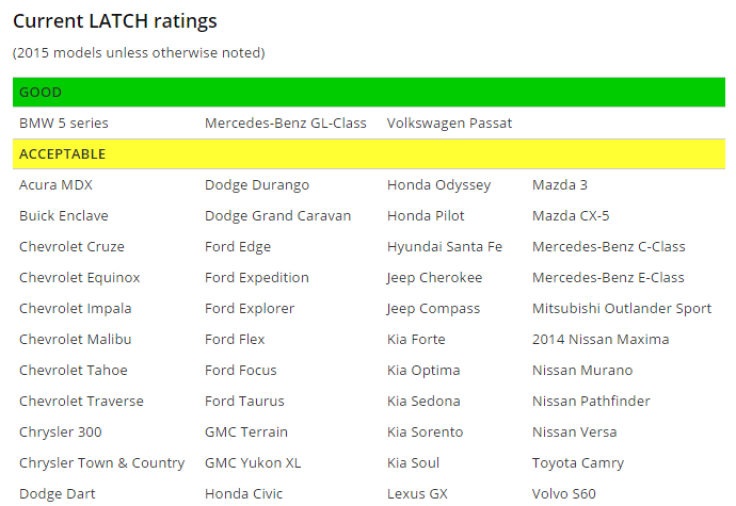

But the IIHS rated more than half of these LATCH as Poor or Marginal, meaning that parents can have a hard time finding the seat anchors or securing the belts to them. Only three cars, all of them German made, met the criteria for being more than just sufficient: the $50,000 BMW 5 Series, the $63,000 Mercedes-Benz GL-Class and the $24,000 Volkswagen Passat.

Some of the worst performers included popular lower priced cars like the Nissan Altima, Ford Fiesta and Hyundai Accent.

IIHS looked at five criteria necessary for a LATCH system get the green light. The lower anchors wedged the seatback, and the lower seat cushion that is used to secure the lower part of the baby or booster seat had to be protruding or less than an inch deep.

A system received lower marks if parents had to push too hard (use more than 40 pounds of force) to get the child seat connector latch onto the anchors. In some of the low-ranking cars, the tether anchors behind a vehicle’s back-row seats were too easily overlooked or confused with other hardware on the back of the seat. If that tether isn’t properly secured, babies or infants could fly forward in front-end collisions and hit the back of the front seats.

Russ Rader, IIHS spokesman, said transportation officials are reviewing an overhaul to current requirements that could adopt some or all of these criteria.

“They’re working on it,” he said. “They’ve said they want to update the LATCH regulation. They’re using our research and the data from the University of Michigan to set more specific criteria. Fed regulations take a long time [to implement].”

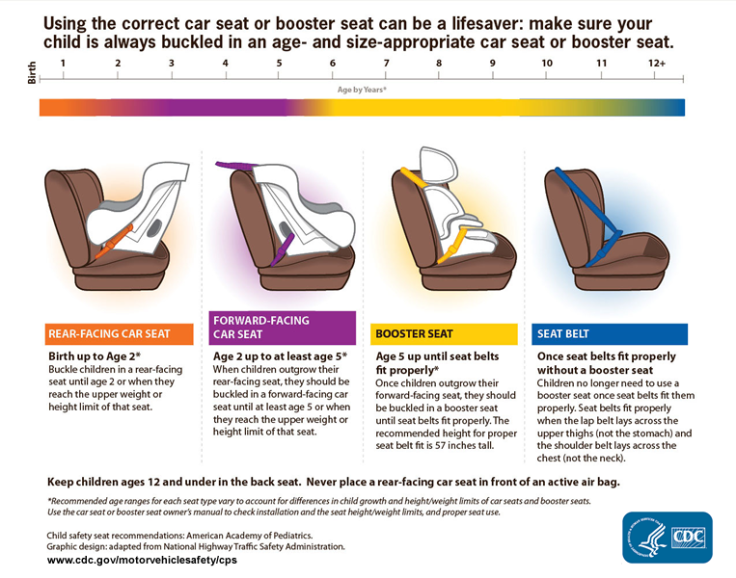

A 2014 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 9,000 American children ages 12 and younger died in automotive accidents from 2002 to 2011. One in three of them weren’t buckled up. Studies have shown baby seats decrease the chance of injury or death in all children too small to use safety belts. While all states have child-restraint laws, only Tennessee and Wyoming specify that car seats or booster seats are required for all children aged 8 or under.

The CDC recommends rear-facing seats for babies up to 2 years old. After that, the seat can be turned forward until the child is about 5 years old. At about 6 years old, children should be placed in booster seats until they’re big enough to be safely secured in a standard seat belt, which occurs roughly at 12 years old.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.