Neil deGrasse Tyson Narrates 'Dark Universe,' Chats About Dark Matter

In about 24 minutes, you can fly through the heart of a supernova, view the hidden web of dark matter that (might) crawl throughout the universe, and watch as galaxies scatter away from you into infinity – all while guided by the soothing voice of Neil deGrasse Tyson.

“Dark Universe,” a new show that opens November 2 at the Hayden Planetarium of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, is sure to astonish astrophysicists and schoolchildren alike. It’s a rare feat for a feature to make you feel just how small you are in the universe, yet simultaneously so privileged to glimpse its beauty.

The new planetarium show enlists the efforts of observatories, supercomputers, artists, NASA satellites, musicians -- and the voice of Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium, popular scientist-communicator, and host of the forthcoming “Cosmos” TV show reboot. But Tyson thinks his words are just the icing on the celestial cake. The story of everything sells itself.

“I’m not twisting your arm to get you to connect to the universe,” Tyson says. “We’re feeding a curiosity that’s already there.”

“Dark Universe” really is a show about everything. It touches on the Big Bang and its lingering background radiation that permeates throughout existence, the gravitational puzzle that led to the dark matter hypothesis, and the even more mysterious force of dark energy that seems to be accelerating the pace at which the universe is expanding.

It’s also a show in beautiful motion – the universe unfolds not as a snapshot but as a vast thing constantly evolving and morphing. Stars don’t just hang quietly in the dark. The paths of galaxies inside a galaxy cluster over the eons start to resemble the movement of organelles in a cell. When the show displays the red-shifted trails of galaxies moving away from our solar system, they hang over the audience’s head like a grand cosmic chandelier.

“We’re trying to show the history and the dynamics of the universe, not just the structure,” says Mordecai-Mark Mac Low, a curator of astrophysics at the AMNH and the science advisor on “Dark Universe.”

As the title indicates, “Dark Universe” is concerned with the puzzling nature of dark matter and dark energy, which together account for about 95 percent of the known universe, according to scientists’ best estimates so far. You might think of dark matter as something lurking millions of light years away, perhaps on the other side of the galaxy or the dark heart of the universe. But it may be closer than we think.

“If dark matter is what we think it is, it may be passing through us right now,” Mac Low says.

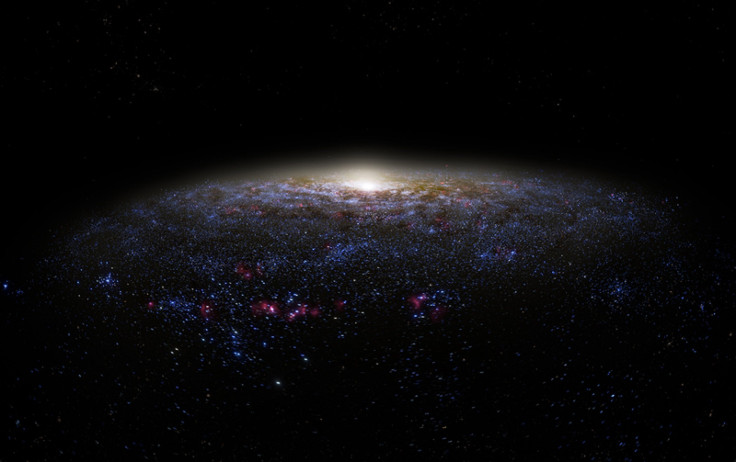

“Dark Universe” contains one of the most advanced imaginings of dark matter yet developed, based on scientific models of cosmic history. As the show imagines it, dark matter looks like a vast web of stuff surrounding and binding the stars (this writer couldn’t help but think of The Force from “Star Wars”).

But there’s still an open scientific debate on the nature of dark matter, which we cannot observe. It seems to neither absorb nor emit light, or any other kind of electromagnetic radiation we’re familiar with. We can only see it indirectly through its rare interactions with regular matter. While many scientists think it might be made of some exotic class of undiscovered particles, Tyson himself is a little skeptical. People with hammers tend to see things as nails, he says – and many of the scientists looking for dark matter are particle physicists.

Tyson said he favors a hypothesis that dark matter isn’t actually made of particles, but is instead gravity leaking in from a parallel universe. Why?

“Because that’s cooler,” Tyson says.

The hordes of schoolchildren that pass through the planetarium every day will surely be inspired by “Dark Universe.” But Tyson thinks that the world doesn’t just need programs to nurture a child’s curiosity about the universe. Most children will naturally ask questions. The real problems arise when the grownups in charge quash that tendency.

What’s missing from the equation is “a program to tell adults how not to discourage kids,” Tyson says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.