New U.S. Science Commission Should Look At Experiment’s Risk Of Destroying The Earth

The spending bill signed into law last month by President Barack Obama provides for the establishment of a blue-ribbon commission to evaluate the cost effectiveness of the Department of Energy’s multi-billion-dollar national laboratories. But the concerns of budget hawks should not be the only focus of the commission’s work. The panel should also consider risks posed by national lab activities as well. In particular, the commission should take a sober look at one experimental program that raises a bizarre and little-discussed prospect of destroying the entire planet.

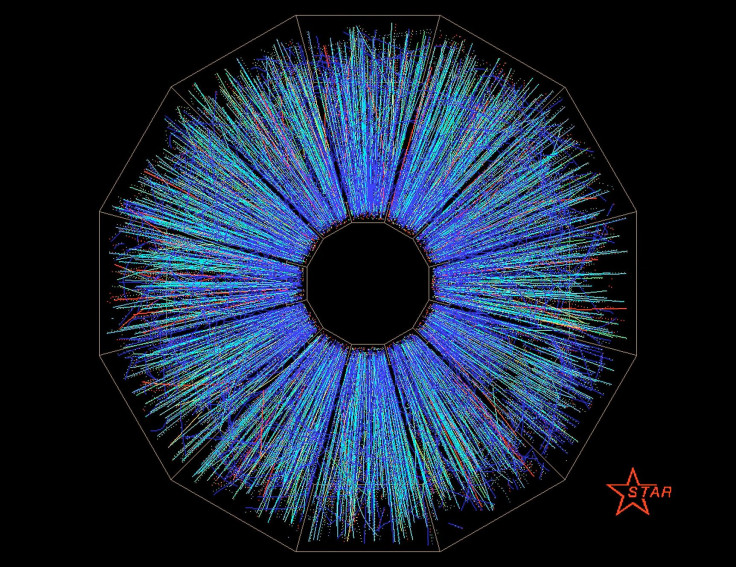

The Brookhaven National Laboratory’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider – called the “RHIC” – accelerates atomic nuclei to nearly the speed of light, then smashes them together. Scientists at the Long Island facility are working to create quark-gluon plasma, a substance believed to have pervaded the universe moments after the ‘Big Bang.’

Yet critics have called for serious attention to the possibility that the collider might generate a subatomic object called a “strangelet,” which could, if certain assumptions are correct, start a chain reaction converting everything into “strange matter.” The process would, according to Sir Martin Rees, Astronomer Royal of the United Kingdom, leave the planet “an inert hyperdense sphere about one hundred metres across.”

Today, the RHIC – pronounced “Rick” – is under scrutiny because of its roughly $160 million annual cost. Last year, a government advisory panel assigned the RHIC the lowest funding priority among major American nuclear science programs. Although the panel’s head saluted the RHIC’s “very, very vibrant program,” the panel recommended shuttering the collider absent significant budget growth.

A focus on dollars is understandable in this era of belt tightening. But funding decisions for nuclear experiments ought to take risks into account as well. If dangerous strangelets are a possibility, then each additional collision of nuclei presents a roll of the dice. And when we are talking about a possible threat to the existence of the planet, even very small probabilities could be of the ultimate significance.

Too little thought was given to risk from the RHIC’s beginning. In July 1999, before the collider opened, a flurry of media interest about the strangelet question prompted Brookhaven’s then-director to gather a team of four scientists to consider the issue. The resulting report, completed by the end of September, concluded the RHIC was safe and that a delay in starting it up was unwarranted. A new round of news stories wrote the controversy’s epitaph.

But after public concerns subsided, critics emerged, assailing the risk-assessment method as flawed. Dr. Rees wrote that theorists “seemed to have aimed to reassure the public … rather than to make an objective analysis.”

Federal appeals court judge Richard Posner noted in his book ‘Catastrophe: Risk and Response’ that the scientists on the Brookhaven risk-assessment team were either planning to participate in RHIC experiments or had a deep interest in the RHIC’s data. Judge Posner pointed out that “career concerns can influence judgment in areas of scientific uncertainty, and scientists, like other people, can be overconfident.”

Even putting aside the weaknesses of the original report, it is nonetheless time for an update. The original report assumed the RHIC would only run for a planned 10 years. But thanks to program extensions, the RHIC is now entering its 15th year. The machine has also been continuously upgraded since the report. After the next round of improvements, it will have increased its ability to produce collisions by a factor of 20 over the original design. Meanwhile, the state of knowledge in nuclear physics has advanced. The suitability of models and assumptions used in the original analysis might be profitably reappraised.

By law, the new nine-member commission is to reflect a broad range of expertise in science, engineering, management, and finance. This gathering of talent is a unique opportunity to ensure the RHIC gets the rigorous, independent risk analysis it has long warranted.

A weakness in the law is that while commission members cannot be employees of the DOE or its contractors, there is no stringent requirement that members not have a career stake in any of the programs. As Judge Posner’s criticism intimated, a desire to participate in or get data from an experiment can erode scientists’ independence. Yet neutrality is essential if the commission is to do its job well. It will be up to Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz to use his discretion to appoint commissioners who are truly free of any personal interest in national laboratory programs.

Also unfortunate, the commission is likely to work slowly. Once formed this spring, the commission’s deadline for submitting its report is February 2015. It would be better if the RHIC risk question was reviewed sooner. Plans for resuming the RHIC experiment are being made and there is some reason to think this next run will present elevated risk. Collisions will be run at a low-energy level, and physicists consider this mode of operation to be more likely to produce strangelets.

While Congress or the courts could review the issue immediately, they are very unlikely to do so. Congress habitually waits until after a full-on disaster to earnestly consider questions of risk. And large-scale science experiments have proved highly resistant to meaningful court review.

Thus, the new commission may be the best hope that the RHIC’s program will get the full scrutiny it deserves. With objectivity and diligence, the commission can work to protect not just the public pursestrings, but the public as well.

Eric E. Johnson is Associate Professor of Law, University of North Dakota and an Affiliate Scholar, Stanford Law School Center for Internet and Society; Michael Baram is Professor Emeritus at Boston University Law School.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.