Nursing’s Workplace Safety Crisis: Bill Aims To Fix Astounding Level Of Job-Related Injuries

When she worked at Iowa City, Iowa’s Mercy Hospital, Melissa Christians had a confused patient who kept trying to climb out of bed. Early on a Sunday morning in February 2010, he tried to use her shoulder to catapult himself over the side rail.

He managed to swing himself over the edge — but not before Christians, a registered nurse, and another nurse technician caught him and put him back into place. The move pulled Christians off her feet and over the side rail, into the bed.

“At first, I didn’t really notice anything,” said Christians, now 44. “I didn’t really feel a pop or pull or anything.”

About a half-hour later, her back felt sore. It got worse the next day, and even worse the month after that. Today, more than five years later, what seemed like nothing more than a minor incident has ballooned into a life-altering affair: Christians said she was fired from her job at Mercy Hospital twice due to extended health-related leaves of absence related to the injury. She has undergone major surgeries to remove herniated disks, fuse her spine, and install a pain-reducing spinal cord stimulator. And she still suffers from nagging discomfort.

“I still have pain every single day in my back and left leg,” Christians said. “Some days are good, some days are bad, but it’s always there.”

Christians recently found work as a nurse at the University of Iowa Heart and Vascular Center, an outpatient clinic that demands relatively little physical exertion. That job came after a long bout of unemployment, prolonged, she believes, by employers’ reluctance to hire a nurse with a history of health problems and who remains unable to lift patients. If she ever lost her current job, she said, “I don’t know who would hire me again.”

A Dangerous Job

Nursing might not come to mind when you think of dangerous jobs. But in terms of work-related injuries, it is, ranking just below such famously risky professions as police officer, firefighter, highway maintenance worker, and correctional officer.

The biggest source of injuries: musculoskeletal disorders like the one suffered by Christians. Often triggered by lifting and moving patients, these sprains and strains can become debilitating, painful and occasionally career-ending ordeals. And yet, as worker safety advocates point out, few healthcare providers have systems in place to reduce these hazards.

A new bill in Congress would force employers to develop them. Introduced last week by Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., and Sen. Al Franken, D-Minn., the legislation would require the U.S. Department of Labor to issue a rule that mandates healthcare providers create so-called safe patient handling policies. That includes everything from installing new equipment to lift patients to granting protections for nurses who refuse to work in unsafe environments.

“This is the biggest industry in the United States and Congress should be very concerned about protecting it -- not just the business, but its workers,” said Keith Wrightson, a health and safety specialist at the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees union, which supports the bill.

Unlike industrial sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing and construction, the healthcare sector has “hardly any standards that protect workers from getting hurt on the job,” Wrightson noted.

Given how fast the sector is growing, the lack of protections is a concern. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the three occupations in the United States with the highest projected increase in employment within the next decade are personal care aides, registered nurses and home health aides. By 2024, more than 1.2 million people are expected to take jobs in these fields.

‘Part of Their Job Is to Defy Health Recommendations’

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, publishes an equation to calculate the recommended weight limits for manual lifting tasks. Originally, it found no single worker should lift more than 51 pounds. But one of the report’s co-authors later determined that for patient-lifting tasks, the limit should be even lower, at 35 pounds.

Most nurses exceed this on a regular basis.

“Basically, part of their job is to defy health recommendations from the experts,” said Emily Gardner, worker health and safety advocate at Public Citizen, a progressive nonprofit based in Washington, D.C.

Moving large weights is routine for front-line healthcare workers: Nurses regularly transfer patients to stretchers or turn them in bed. Other times, they might provide physical support in the shower, or walk their patients to the bathroom.

Without mechanical aids or clear guidance from management, this sort of daily physical effort can lead to serious injuries, according to occupational health experts.

Nevertheless, most hospitals and healthcare providers have no comprehensive safety policies, a report from Public Citizen found this summer. Experts estimate that anywhere from just 3 percent to a quarter of providers do, according to the report.

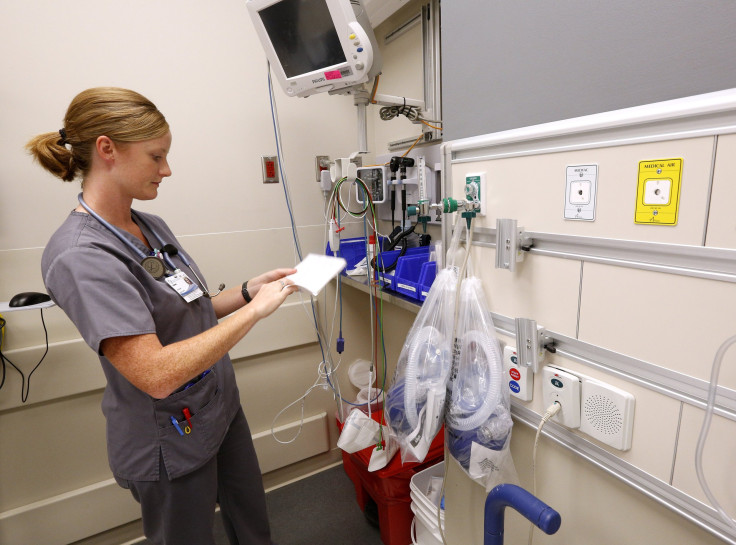

These so-called safe patient handling policies include -- on the one hand -- the use of technology to reduce the strain on nurses. Ceiling-mounted and floor-based lifts, for instance, can easily move patients to and from their beds, replacing the grueling labor of a manual transfer.

Safe patient handling also refers to the idea of a broader safety-focused culture: clear lifting practices and policies spelled out in writing, training programs, worker-represented safety committees, and data collection measures, for example.

Healthcare providers that have adopted such policies have reaped clear rewards, according to the Occupational Safety Health Administration (OSHA), the federal agency that regulates workplace safety in most of the private sector.

Among the success stories it cited in a recent report was the Veterans Health Administration's introduction of safe patient handling programs at seven Southern facilities in 2001, which saved $200,000 a year from decreased workers’ compensation claims. Meanwhile, after Stanford University Medical Center adopted its program it saw five-year net savings of $2.2 million, cutting costs from workers’ compensation and reducing pressure ulcers in patients.

Why Hasn’t It Happened Yet?

A dozen states have adopted their own safe patient handling regulations. But hefty political roadblocks stand in the way of a nationwide mandate.

For one, business groups are not enthusiastic. The American Hospital Association did not respond to a request for comment, citing the holidays. In the past, the lobbying group has opposed legislation similar to the recently introduced bill.

Testifying before a Senate hearing in 2010, Douglas Erickson, vice president at the Facility Guidelines Institute, an organization that focuses on the design and construction of healthcare facilities, warned of the high costs of a mandate. Most facilities, he said, “are not designed and constructed to accommodate the installation of fixed lifting equipment.” New requirements would “waste a tremendous amount of healthcare resources,” he added.

Gardner bemoans this approach.

“Industry is really shortsighted,” she said. “They’re fixated on short-term costs of retrofitting rooms with equipment, but they’re going to end up saving money in the long-run.”

There’s also tremendous hostility from Republicans. The GOP tends to oppose new workplace safety regulations in general. (Opposition to a proposed rule that would reduce workers’ risks of contracting silicosis, a fatal lung disease, is the latest example.) But on top of its broad-based anti-regulatory ideology, the party has a particular history when it comes to rules having to do with manual lifting.

In 2000, OSHA issued an ergonomics standard that called on employers to screen for hazards such as lifting heavy weights, and then take steps to address the risks. The following year, with help from President George W. Bush, the Republican majority in Congress repealed the rule, citing high costs and the fear of burdensome effects on business. Observers say that vote has effectively blocked OSHA from issuing any new regulations on the subject without first getting congressional support.

The legal reasoning remains up for debate. At any rate, it’s clear the political impact of the repeal looms large. Since 2001, OSHA has steered clear of creating any new rules on safe patient handling.

The latest bill from Conyers and Franken is designed to grant the agency explicit authorization from Congress to take action. It’s also meant to stir up political support at large.

Whatever the path to a mandate is, Keith Wrightson says safe handling systems are long overdue across the country. “It’s a cruel irony” that healthcare providers haven’t acted alone, he said. “They don’t bother to care for their employees.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.