Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Sufferer Calls For More Attention, Discussion

Opinion

I remember vividly as a young child being scared of my bedroom and of nighttime, so I conjured up a way to calm myself: By checking every nook and cranny in my room. Then rechecking them.

Under my bed, behind my mirror, in the closet -- my examinations always followed the same pattern. If I deviated, I had to start over. After that, I’d sneak down the basement stairs, the ones next to my room, to ensure the evil iron was unplugged. I had to check that several times, too. Up the stairs and back down, just to be absolutely certain it didn’t somehow magically get plugged in while I wasn’t watching, or perhaps, because I wasn’t seeing it properly.

This checking ritual was a nightly occurrence; it calmed my nerves and made me feel in control -- as if I were preventing bad things from happening by performing the routine procedure.

It inevitably led to similar behaviors beyond the evening. Even as a child, I realized it was abnormal behavior, but I couldn’t stop it. The pattern had already firmly established itself. A pattern that, today, 50 years later, still impacts my daily life. Although I have managed to hide my condition from everyone but those who live with me, my mind is never free from my obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD.

The day I learned that what I suffered from was fairly common, and actually had a name, was a turning point in my life.

I was sitting in a doctor’s office waiting for one of my children to be seen when I caught sight of a brochure emblazoned with: Facts about Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. I had never heard of it, but the name was certainly intriguing so I took the pamphlet with me. Later, at home, I had tears running down my face as I read it, realizing that what I suffered with for so many years was a bona fide disorder, and that lots of people have it. Knowing I was not alone was somewhat vindicating.

My disorder is the hardest thing to talk about. In fact, it’s something I don’t talk about -- other than admitting to having it. Sure, I sometimes off-handedly joke about it, play it off as something insignificant, a disorder that brings about amusing habits, when, in reality, it’s at all amusing.

Nor is it insignificant: it’s so completely personal. OCD is what is going on in my head. It’s a glimpse into how I think, which offers a glimpse at the very core of who I am. And, let’s be honest, the way I think about some things is clearly not normal.

Very few thoughts go through my head without bypassing the OCD filter. Do I do this again? Do I retype that sentence? Do I reread that sentence? It’s always there, intrinsically a part of me. Truthfully, I’m just not sure I am capable of opening and closing a drawer once.

Not much attention is given to OCD. The medical community is too silent about it, as is pop culture. Minus a few television and movie characters -- Monk, the brilliant TV detective and Jack Nicholson in “As Good as it Gets,” a social pariah as a result of his OCD -- you barely see it. Where literature is concerned, Steve Martin wrote a wonderful book about a guy with extreme OCD. “The Pleasure of My Company” is a warm and empathetic story about a person with a disorder that seems too bizarre to be real.

These are the only examples I can think of that portray OCD sufferers.

To think of how common OCD is, it also seems odd that the disorder doesn’t get a lot of attention. Research shows that 1 in 100 people suffer from OCD in some form. Some have it as a child; others develop it as young adults. There are varying degrees of severity. For some, it is so severe they can’t lead a normal life and may not even leave their home. For others, it is more of a mild annoyance.

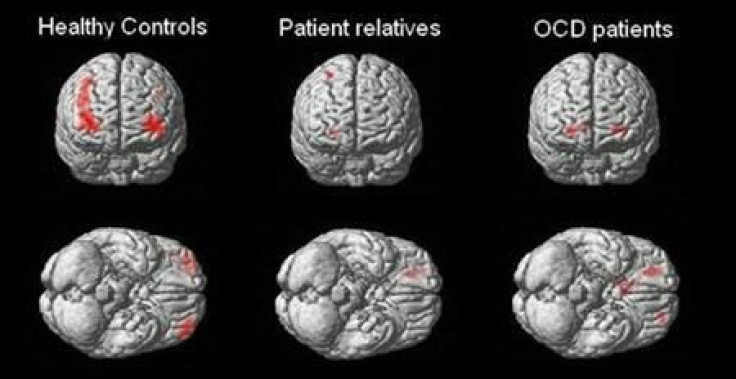

Researchers don’t have all the answers yet, but what they do know is that a problem in the way the brain works is the cause. The reason OCD gets little attention is because it’s not a flashy disorder. People don’t die from it, and most people hide it out of embarrassment or lack of knowledge about what it is. But it is serious and can affect your quality of life.

It’s time to have a bigger discussion about it.

For me, having OCD hasn’t stopped me from doing anything in life. In fact, I’d say I’ve gone out of my way to overcompensate of it, as if I’m trying to prove to myself that I am in control. As an example, I got married at 19 and two days later moved to Iran, where I lived for a year and a half. I think I did it to prove to myself that I am capable of doing anything, that no disorder was going to keep me from living my life fully.

And I have.

I have been a well-known, on-air broadcast professional for 30 years; I have traveled the world and have owned several successful businesses. I have an incredible marriage and two great (normal) sons who are aware their mom sometimes does pretty weird things. I may have been successful because of my disorder, who knows? But I am proof that it doesn’t have to stop you.

While there is no cure, there is no need for the estimated 3.3 million people with OCD to suffer because medication and therapy treatments are now available to help deal with it. I have done neither, choosing rather to deal with it myself. The reasons vary, but namely because I don’t want to be on medication forever, because I don’t want everyone knowing I suffer from it, and because I don’t want to list a medical condition for which an insurance company could charge me a higher premium.

The biggest reason, though, is because for more than 30 years I didn’t know what it was, and was already coping with it.

But it doesn’t have to be that way for OCD sufferers today. This is why a broader discussion should be had. People should know it isn’t shame-worthy, that seeking help isn’t a negative.

Suffering from OCD is a lonely thing because it’s all in your head. So, if you feel the need to turn the faucet off and on a certain number of times (my number is four), or you can’t bear to step on a crack in the sidewalk, know that you are not alone and that you can overcome it.

It doesn’t define you, it just makes you work harder, think differently, notice everything. I don’t celebrate my OCD, but it has made me a stronger person.

Ann Craig-Cinnamon has spent 30 years in both radio and television broadcasting in the Indianapolis market. Featured in a documentary shown on PBS called “Naptown Rock Radio Wars,” Craig-Cinnamon is a trailblazer in radio.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.