Oklahoma Earthquakes 2015: Tremors Rise As Oklahoma Officials Struggle To Stem Fracking Wastewater Flow

NORMAN, Oklahoma -- The ground shook throughout Oklahoma in recent days, including near the crucial Cushing oil storage hub. A 4.5-magnitude earthquake struck Oct. 10 just miles from the fields of white round tanks that hold the largest share of U.S. crude stockpiles, sparking fears among residents of potential explosions. A separate tremor in north-central Oklahoma sent homes and buildings gently swaying on the opposite side of the state, as far south as Norman and Oklahoma City.

Such shaking has become routine in parts of Oklahoma, where oil and gas companies are injecting unprecedented volumes of wastewater into the ground and inducing earthquakes, scientists have confirmed.

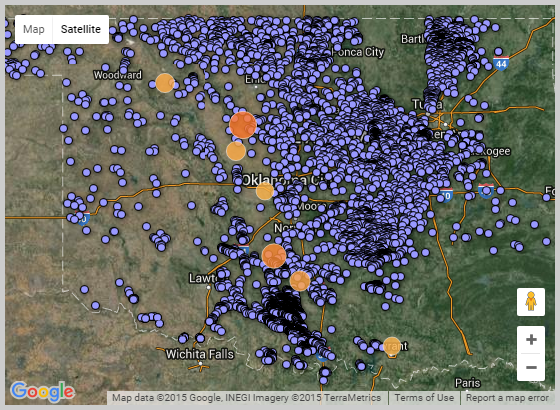

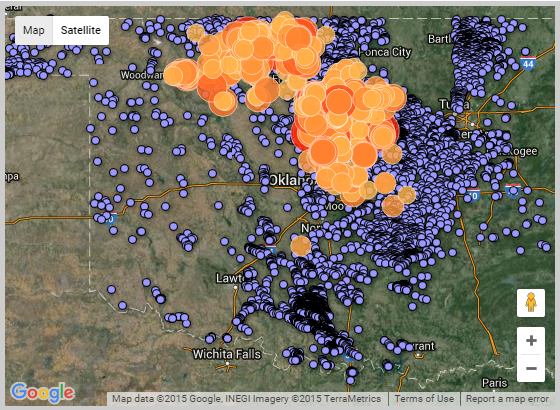

Oklahoma surpassed California last year as the earthquake capital of the lower 48 states and will likely beat the Golden State in 2015. Nearly 700 earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or greater have rocked Oklahoma this year, a more than 300-fold leap from the start of the drilling boom in 2008. Insurance claims are rising as foundations crack and bricks crumble, while geologists are warning of the unknown long-term effects of continuously rattling an entire state and pumping it full of wastewater.

Oklahoma officials say they are still struggling to devise a strategy to reduce seismic activity without strangling the energy industry, the state’s largest employer. The government has resisted calls from environmental groups to place a temporary ban on new wastewater injections while agencies and companies study the phenomenon. The Oklahoma Corporation Commission, which regulates the oil and gas sector, has taken some steps to reduce earthquakes, including limiting permits for new wells in “areas of interest” and requiring certain disposal wells to temporarily shutter or reduce water intake if shaking occurs nearby.

But scientists in the state say those measures haven't been enough to drive a sharp decline in earthquakes. With existing efforts, “We might see a little bit of a plateau in the rate,” said Kyle Murray, a hydrogeologist at the Oklahoma Geological Survey. He noted it could take six months to two years to see the full effect of any pullback in wastewater injections. “We’re responding to it and trying to understand it better at this point,” he said during a recent tour with reporters to oil and gas facilities in central Oklahoma.

Oklahoma’s drilling renaissance began around 2008, when global oil prices surged into the triple digits. At the time, Oklahoma was blanketed with older oil wells that producers had abandoned in the 1990s. The aging wells required sucking up copious amounts of brackish wastewater to reach the remaining oil reserves. With prices high, however, and with the advent of new “dewatering” technologies, producers could afford the extra hassle. Unconventional techniques, including hydraulic fracturing, or fracking -- another wastewater-intensive process -- further ignited the drilling boom.

As oil and gas production climbed, so too did the volume of brackish and fracking wastewater being injected into Oklahoma’s geological formations. Most of the recent earthquakes have occurred in the Precambrian basement rock, which underlays the Arbuckle Group rocks. In the Arbuckle, the number of disposal wells has nearly doubled, from 430 wells in 2009 to 830 wells in 2014. Wastewater volumes in the region rose 140 percent over the same period, from at least 18.2 billion gallons to at least 43.8 billion gallons, according to estimates provided by Murray.

Other oil- and gas-rich states experienced an unusual rise in seismic activity, though none as high as Oklahoma. Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, Ohio and Texas have all observed earthquake swarms, most likely due to wastewater injection activity. With global oil prices down by more than half from June 2014, oil and gas production is slowing nationwide. Yet in Oklahoma, wastewater volumes are still growing, and the state is projected to log hundreds more magnitude 3.0-and-greater earthquakes by the year’s end, federal seismologists project.

Skepticism Reigned

Despite Oklahoma’s insistent shaking, state officials for years expressed skepticism that the earthquakes could be linked to the dramatic climb in underground wastewater disposal. The Oklahoma Geological Survey, part of the University of Oklahoma, resisted making definitive statements about the cause of quakes, and often implied the tremors were natural. The Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association, an industry group that works closely with regulators, insisted more research was needed to prove a correlation.

Energy companies have said that disposing of wastewater is central to their operations, and that any effort to halt or significantly curb injections would bring their oil drilling and fracking operations to a halt. Continental Resources, one of Oklahoma’s largest oil and gas companies, pioneered the technology to draw water from aging wells.

Recent investigations by Bloomberg, EnergyWire and other media outlets suggested the energy industry steadily pressured scientists in Oklahoma to slow their research on earthquakes and injection wells, or at least keep their findings from the public. Emails obtained by the outlets through public-records requests implied that Continental in particular played a role in fostering confusion among agencies and the public.

In one instance, Austin Holland, then the state’s seismologist, was reportedly summoned in 2013 to a meeting with Harold Hamm, Continental’s influential founder, and David Boren, president of the University of Oklahoma and a Continental board member. Holland and his colleagues were inching closer to linking quakes to wastewater injections. During the meeting, Hamm requested that Holland be cautious when publicly discussing his research. “It was just a little bit intimidating,” Holland, who has since left the job, told Bloomberg this spring.

Boren -- a Democrat who is a former governor and U.S. senator from Oklahoma -- and Hamm insisted the meeting was purely informational. Continental also dismissed insinuations of industry influence as “offensive and inaccurate,” Bloomberg reported.

'It Is Not Natural'

Oklahoma officials have since dropped the ambiguity. The Oklahoma Geological Survey in April launched a website, called Earthquakes in Oklahoma, that clarifies that oil and gas activity is “very likely” causing the seismic swarm -- a departure from the survey’s earlier suggestion that natural causes were probably to blame.

“We absolutely have an earthquake problem, and it is not natural,” Michael Teague, Oklahoma’s secretary of energy and environment, told reporters from the grounds of a saltwater disposal well in Grady County.

But Teague said the state is still not sure what precisely is triggering the quakes -- wastewater volumes, injection pressures, locations, depth of the wells, or a mix of all those factors? Oklahoma regulators for now are exploring whether wells drilled tens of thousands of feet deep are inducing earthquakes, he said. In neighboring Kansas, state agencies are reducing well volumes to see if that tactic prevents earthquakes near the Oklahoma border.

“There’s a lack of agreement as to what would be effective,” said Kim Hatfield, president of Crawley Petroleum who sits on the board of the Oklahoma Independent Producers Association. “We need to figure out how to do it safely.”

Hatfield said he disagreed with the finding that injection wells are directly causing earthquakes. Rather, he said the wastewater is triggering seismic events that likely would have occurred naturally within five to 10 years. “They could’ve happened anyway,” he told reporters seated on a coach bus. “They’re just happening earlier than they would have because of injection wells.”

George Choy, a senior scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey in Golden, Colorado, challenged that argument. Oklahoma’s recent earthquakes “would not have occurred for hundreds and hundreds of years without the intervention of human activity,” he said, sitting near Hatfield on the bus. “The faults wouldn’t have moved without the introduction of water.”

Wastewater injections in general can cause earthquakes by prying fault lines apart, the U.S. Geological Survey explained on its website. Normally, faults are pushed together by overlying rocks; the weight and stress applied by these rocks boosts the fault’s frictional resistance. But injected wastewater, depending on volume and location, can counteract these forces and cause faults to “slip,” which induces earthquakes. Still, the majority of the country’s injection wells -- of which there are more than 144,000 nationwide -- do not cause earthquakes, Choy said.

No Legal Authority

Teague said the state is aiming to reduce wastewater injection volumes to levels from 2012, the year before earthquakes began to spike. But he said the state is not considering a temporary ban on wastewater injections to accomplish that goal. He said Republican Gov. Mary Fallin’s administration doesn’t have the regulatory authority to impose a moratorium. The Oklahoma Commission Corporation, the industry regulator, has also said it doesn’t have the legal means to enforce a ban.

Even if they could, however, “A moratorium is not the right answer,” Teague said, pointing to the oil and gas industry’s outsized role in Oklahoma’s economy.

The sector accounts for about 20 percent of all jobs in the state and about two-thirds of the jobs created since 2010, when the economy began rebounding from a recession, economists at Oklahoma City University found. A forced slowdown in oil and gas activity would further likely exacerbate the industry’s slump from low oil prices, hurting the state budget. Revenues from oil and gas taxes shrank in all but two months of the past year, compared to the previous annual period, Oklahoma Treasurer Ken Miller recently announced.

Reducing Oklahoma’s deluge of wastewater will require updating the state’s regulations to encourage recycling and reuse of the salty brine. More efficient extraction technologies could help leave more water in the original oil well. And better seismic monitoring and 3-D mapping could help operators avoid the areas where earthquakes are most prone to striking.

As state agencies and energy companies hash out the details, more tremors will keep roiling the state. At least five quakes of around magnitude 3.0 were observed since Sunday.

Update 10/14/15: An earlier version of this story inaccurately described the location of Oklahoma's earthquakes as in the Arbuckle Group rocks. The majority occur in the Precambrian basement rock, which underlays the Arbuckle Group.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.