Panama Canal Expansion: Three Facts About Controversial ‘Panamax’ Project

Eight years and more than $5 billion later, the Panama Canal expansion is set to open Sunday. The deeper, wider channel is designed to accommodate the world’s growing fleet of mega cargo ships and expanding trade between North America and the Far East.

The controversial project slicing through Central America came in hundreds of millions of dollars over budget and missed its planned completion date of June 2015. Its opening next week also comes at a difficult time for the global commercial shipping market, with low oil prices, sluggish growth in China and other factors dampening traffic and income at the Panama City landmark.

Jorge Luis Quijano, the canal’s administrator, said he’s not worried about the less-than-fortuitous timing. “The world will continue to grow,” he told the Associated Press. “Eventually there will be a rebound, and the good thing is that we are prepared to take advantage of that when it occurs.” Here’s three key facts about the Panama Canal expansion:

1. Double the Shipping Fun

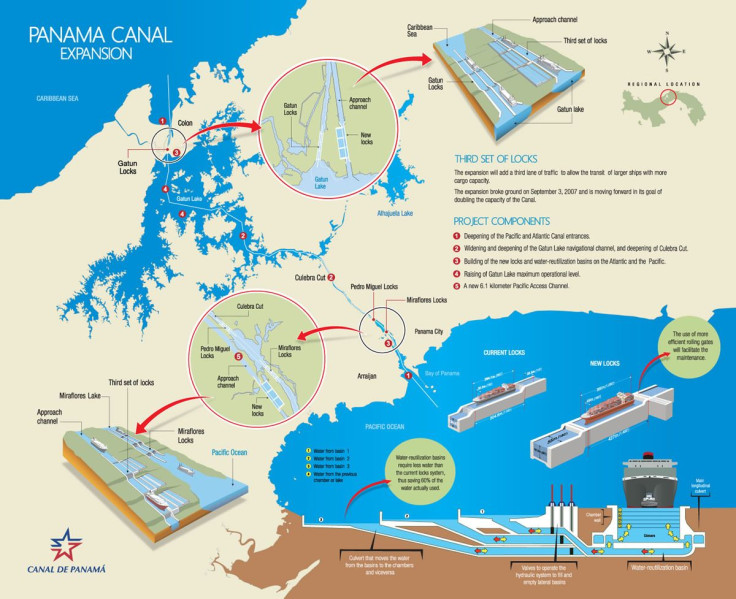

The expansion, which began in September 2007, will double the capacity of the existing, 101-year-old Panama Canal by adding a new lane of shipping traffic and building a new set of locks. With the current locks, only vessels that can carry up to 5,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) can pass through the canal. Starting next week, vessels with nearly three times the carrying capacity — around 14,000 TEUs — will be able to glide through the shipping channels.

Megaships are on the rise as logistics companies strive to move higher volumes of goods using less fuel. In California late last year, the largest container ship ever to unload in North America arrived at the Port of Los Angeles. The CMS CGM Benjamin Franklin stretches 1,300 feet — about as long as the Empire State Building is tall.

Canal authorities estimate the expansion, called Panamax, will cut global maritime costs by an estimated $8 billion a year by enabling companies to pack more goods onto fewer ships. About 5 percent of the world’s total cargo volume currently moves through the canal.

2. International Investors

To expand the waterways, the Panama Canal Authority signed contracts worth $2.3 billion with a group of bilateral and multinational credit institutions, including: Japan Bank for International Cooperation ($800 million); European Investment Bank ($500 million); Inter-American Development Bank ($400 million); Washington-based International Finance Corporation ($300 million); and Development Bank of Latin America ($300 million).

Adding a third set of locks cost about $3.2 billion. Canal authorities awarded the lock contract to a global consortium in July 2009. Grupos Unidos por el Canal S.A. (“Groups United for the Canal”) includes manufacturing and construction firms from Panama, the United States, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain.

3. Moving More U.S. Goods

U.S. companies ship billions of dollars in bulk and containerized cargo through the Panama Canal each year, particularly agricultural commodities like cotton and wheat, which travel from U.S. Gulf Coast ports to importers in Asia. The expanded canal may also help move the rising volumes of U.S. energy exports, including crude oil, petroleum products and liquefied natural gas (LNG), a U.S. Department of Transportation report said.

In January, America shipped its first export of crude oil in four decades after President Barack Obama lifted a ban on U.S. oil exports. Rising shale oil drilling in states like Texas and North Dakota put pressure on lawmakers to lift the ban, especially as U.S. refineries struggled to keep pace with the supply boom. With U.S. demand growth expected to flatten in coming years, producers are eager to sell their crude in China and other emerging markets.

The U.S. also recently began exporting LNG, an emerging fuel for power plants and vehicles. Cheniere Energy in February shipped the first tanker of LNG from its hulking, $18 billion Sabine Pass terminal in Louisiana. Five other LNG export terminals in the U.S. are under construction, and federal regulators have approved four more.

Panamax “is a huge plus for crude exports heading to Asia. It’s a real plus for LNG,” said John LaRue, executive director of Port Corpus Christi in Texas, which handled the first export of U.S. crude since Obama lifted the export ban.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.