Paris Climate Conference 2015: $2.2 Trillion In Future Fossil Fuel Spending At Risk As World Leaders Take On Climate Change

Diplomats gearing up for make-it-or-break-it climate negotiations in Paris starting next week have set their sights on 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) -- the most the Earth can safely warm, scientists say. But to keep under that threshold, negotiators might target a second figure: $2.2 trillion.

That’s the amount of potential future spending the world’s fossil fuel extractors would need to avert in order to keep climate change in check, a new report argues. From coal development to shale oil exploration, the world’s largest energy companies would face drastic shifts to their business plans if world leaders resolve to heed scientists’ advice on capping carbon emissions.

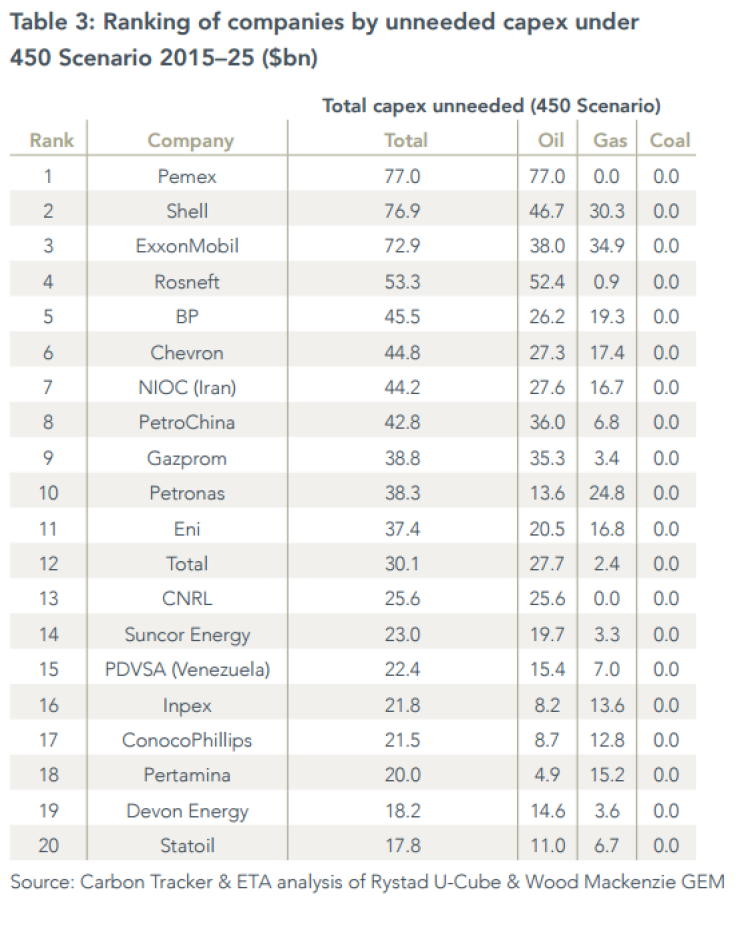

ConocoPhillips (NYSE:COP) would have to abandon $22 billion in spending on new and existing projects, the report estimates. Chevron (CVX) would have to shave $45 billion from its expected capital expenditures. For Royal Dutch Shell (NYSE:RDS.A), the total is $77 billion.

That could come as a wake-up call for shareholders in oil and gas companies. And coal investors could be in for a worse shock. In a future that avoids cataclysmic climate change, “no new thermal coal mines are necessary,” the report states.

“Investors are trying to shift toward a 2 degree world,” said James Leaton, research director at the Carbon Tracker Initiative, the U.K. organization that produced the report. “Parts of the private sector still need a stronger message about the direction of travel.”

It remains an open question, however, just how thoroughly major oil and gas companies have prepared investors for a future where carbon emissions are capped and alternative energy sources proliferate. Publicly traded companies are obliged to inform shareholders about future risks to profits, and for years, oil majors have provided warnings in securities filings as to potential impacts on earnings from legislation related to climate change.

But some find those often terse disclosures insufficient. “I don’t think the true urgency and the true severity of the consequences have sunk in yet to the majority of the investing community,” said Patrick Parenteau, a professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School.

Regulators have heightened scrutiny on the energy companies’ disclosures surrounding climate change. Earlier this month, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman reportedly issued a subpoena to Exxon Mobil over allegations that the company long understood the consequences of global warming but actively sought to hide the risks from shareholders and the public. Exxon denies the allegations.

Now, as climate researchers are developing ever more precise estimates of how energy industry players will be affected by climate change and measures to mitigate it, organizations like Climate Tracker are pushing companies to outline more detailed scenarios for shareholders.

To Leaton, the problem isn't that fossil fuel companies like Exxon and Shell lack the knowledge. It's investors who could be missing out. “They have teams of economists and researchers looking into this,” Leaton said of the companies. “What we find is they don’t actually publish all they’ve found.”

'These Fuels Can’t Be Burned, Period'

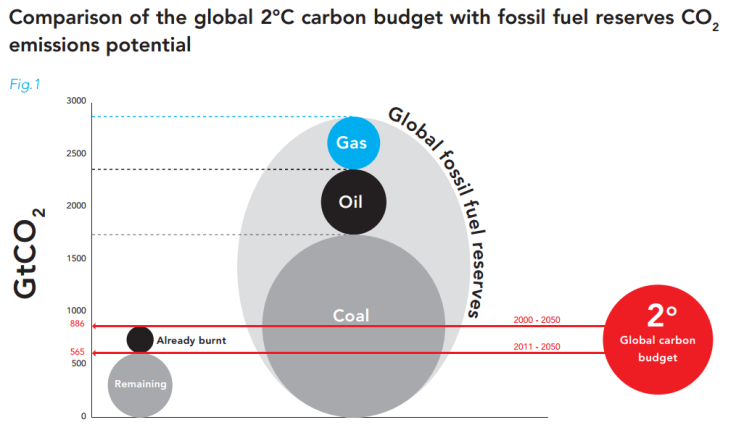

The calculations in the report stem from the widely accepted notion of a carbon budget. The idea is that there is only so much oil, gas and carbon that humans can burn before climate change spins out of control. International scientific bodies have put that total at roughly 1,000 gigatons, or 1 trillion tons, of CO2.

Scientists estimate that fewer than 485 gigatons remain in the budget. Yet energy companies and state-owned drillers have already booked more than three times that total in their untapped inventories. “The total quantum of coal, oil and gas in the world far exceeds any reasonable carbon budget to limit global warming,” the report states. The $2.2 trillion of cutbacks in drilling and mining outlined in the report would reduce carbon output from new and existing projects by 156 gigatons.

That creates a quandary for the industry. “It’s not an environmental argument, it’s a business argument,” said Parenteau. “At some point in the not too distant future, the world will come to the conclusion that these fuels can’t be burned, period.” When that happens, he said, the fossil fuel industry will be squeezed simultaneously by new laws, such as carbon taxes, and falling prices for wind and solar energy.

As an example, Parenteau points to the coal industry. Following new environmental regulations and falling profit margins, the most carbon-intensive energy industry has seen dozens of bankruptcies in the past year. An industry report in September estimated that more than 10 percent of U.S. coal came from companies in some stage of bankruptcy.

“There’s a pretty stark message that we don’t need any more coal,” Leaton said.

But change will come slower to oil and gas, which are still deeply embedded in the global economy. “We don’t fly airplanes with electricity yet,” Parenteau said.

Dueling Scenarios

The Carbon Tracker Initiative argues that companies like Chevron and Shell should unveil more detailed climate projections for shareholders. Specifically, the organization wants to see fossil fuel giants publish reports like the International Energy Agency’s 450 Scenario, which envisions the changes necessary to keep warming under 2 degrees.

Though foreign companies like the Anglo-Australian BHP Billiton and the Norwegian Statoil have produced such estimates, no major American energy producers have shared low-carbon scenarios with investors.

Still, it’s clear that in the U.S., efforts to mitigate climate change could strike deeply at industry growth. To avoid hitting climate limits, 39 percent of new and existing U.S. coal projects would need to go by the wayside, the report calculates, along with 3o percent of gas and 16 percent of oil capital spending.

But that doesn’t mean an instant death sentence. Instead of investing in constant growth, Leaton said, oil and gas drillers should be focusing on repositioning their existing assets for future demand. “The challenge will be a changing culture at the board level and the mandate of engineers to get more stuff out of the ground.”

Major U.S. energy producers reject the report’s findings. A spokesman for Shell told International Business Times that Carbon Tracker exhibits “critical misunderstandings” surrounding key energy topics, noting that the organization opted to ignore the “huge potential” of carbon capture technology to reduce emissions. (The report notes that carbon capture technologies, which are expensive, would have to expand 150 times over previous levels to have an appreciable effect.)

The Shell spokesman added that renewable energies would play a crucial role in future energy markets.

Chevron also acknowledged the importance of new technologies, though spokesman Kurt Glaubitz did not comment on the specifics of the Carbon Tracker report. “Policies should be pursued that support research, innovation and application of breakthrough technologies that can be adopted globally, at scale and without subsidies,” Glaubitz said.

ConocoPhillips did not respond to queries about the report, but shared its climate policy.

Each of the companies has acknowledged the existence of climate change and pointed to potential responses, like carbon capture technology. But Leaton said those disclosures don’t cut it. “You need better information flow through the market and more scrutiny on where that money is being spent,” he said. “Some companies are still heading in the opposite direction.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.