Is Pluto Made Of A Billion Comets Joined Together?

As the early days of our solar system were extremely chaotic, there have been varying theories regarding the formation of different planets and their moons. It is still impossible to delve into the exact history of each celestial body in our neighborhood, but a new study hints Pluto, the tiny body which was stripped of its planetary status and reclassified as a dwarf planet, might have one of the best origin stories on offer.

This is because, according to the new work led by scientists at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), the dwarf planet came to be with the agglomeration of a billion comets at the edge of our solar system. The group posited this theory after running cosmological models using NASA’s New Horizons data on Pluto and findings of European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission on comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

“We’ve developed what we call ‘the giant comet’ cosmochemical model of Pluto formation,” Christopher Glein of SwRI’s Space Science and Engineering Division said in a statement.

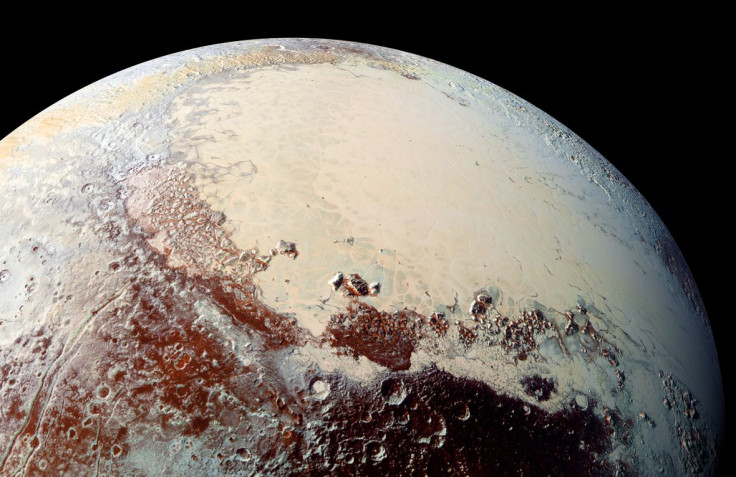

With this, they found the nitrogen content in Sputnik Planitia, a large ice glacier located on the left side of the bright, heart-shaped feature on the surface of Pluto is similar to the composition expected from a mix of several 67P like comets.

“We found an intriguing consistency between the estimated amount of nitrogen inside the glacier and the amount that would be expected if Pluto was formed by the agglomeration of roughly a billion comets or other Kuiper Belt objects similar in chemical composition to 67P, the comet explored by Rosetta,” Glein explained.

To estimate post-formation nitrogen content in the atmosphere (98 percent at present) and glaciers of Pluto, the researchers predicted how much of the gas could have leaked out into space over several billion years and reconciled with the proportion of carbon monoxide to nitrogen on the planet. As Glien said in the release, the low abundance of carbon monoxide suggested “Pluto’s initial chemical makeup, inherited from cometary building blocks, was chemically modified by liquid water, perhaps even in a subsurface ocean.”

The group also ran a solar model that suggested Pluto might have formed from very cold ices that would have had the same chemical composition as that of the sun, but nitrogen and carbon monoxide content in that particular model didn’t match as much as it did in the comet model.

The work builds on the success of New Horizons and Rosetta missions and hints at Pluto’s interesting origin and evolutionary story, but this is just the beginning and the results might change with time.

“Using chemistry as a detective’s tool, we are able to trace certain features we see on Pluto today to formation processes from long ago,” Glein concluded. “This leads to a new appreciation of the richness of Pluto’s ‘life story,’ which we are only starting to grasp.”

The study, titled “Primordial N2 provides a cosmochemical explanation for the existence of Sputnik Planitia, Pluto,” was published May 23 in the journal Icarus.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.