How Citizens United Made It Easier For Bosses To Control Their Workers’ Votes

The Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision is most famous for the torrent of outside ad spending it unleashed on the American election system. But the ruling did more than just lift caps on outside political expenditures; it also gave corporations more leverage over the political behavior of their employees.

Citizens United eliminated restrictions on the ability of employers to lobby their workers in support of particular candidates and causes. Bosses can even make employees attend partisan political events during work hours.

In addition to now being legal, those tactics are also effective, according to new research by Paul Secunda, a law professor at Marquette University, and Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, a doctoral candidate in government and social policy at Harvard. A survey they conducted for an upcoming UCLA Law Review paper found that workers are generally responsive to political pressure from their managers.

Hertel-Fernandez and Secunda surveyed more than 1,000 workers, many of whom worked at companies like Cintas and Georgia-Pacific, both of which sent political messages to their workers during the 2012 presidential race. Those two companies warned employees that their jobs could be negatively affected if management didn’t get its way in the election. (Georgia-Pacific is a subsidiary of Koch Industries, the company run by the billionaire conservative activist brothers Charles and David Koch.)

“Workers who received warnings such as those from Cintas or Georgia-Pacific were about three times as likely to indicate that they were uncomfortable with employer messages as workers who did not receive these warnings, according to the results from Hertel-Fernandez’s survey,” write Secunda and Hertel-Fernandez. “These warnings were also apparently effective at changing workers’ political behaviors and attitudes: A worker who received at least one such warning about potential economic losses was about twice as likely to report responding to their employers’ political requests compared to workers who received no such warnings.”

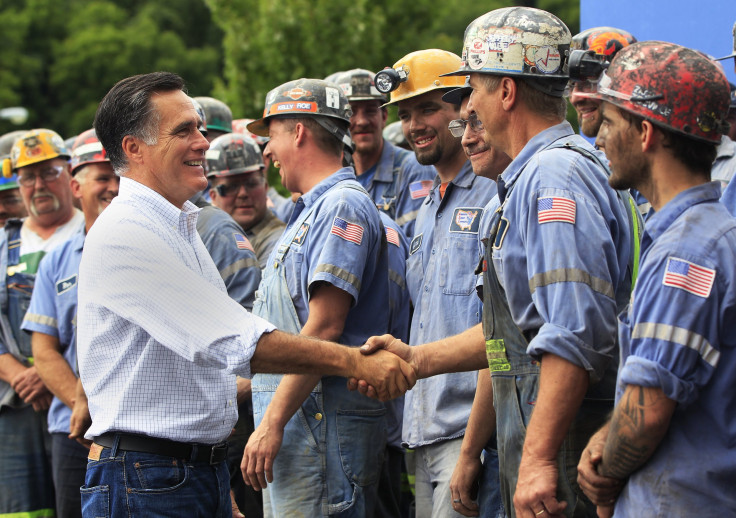

Some companies go even further than Cintas and Georgia-Pacific. Also in 2012, the coal firm Murray Energy ordered workers from an Ohio mine to appear at a rally for Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. The rally took place during normal work hours, but miners were not paid for the day. A Murray executive later explained, “Attendance was mandatory but no one was forced to attend the event.”

Workplace political coercion is particularly effective because recent advances in office surveillance make it easier for managers to target their political messaging, Secunda told International Business Times.

“There are apps that tell you who opens your emails instead of deleting them, so employers are able to gauge very quickly who are their champion employees and who are their trouble employees,” said Secunda. Management can subject those “trouble employees,” he added, to “various forms of subtle retribution and retaliation” without legal consequences.

Hertel-Fernandez and Secunda surveyed managers at companies that subject their employees to political pressure and found that businesses are quickly acclimating to their newfound freedom.

“Managers are very clear that they’re doing this on an unprecedented basis,” said Secunda. “They’re being directed to do so, and in fact a lot of managers are not at all shy about doing it. They think they should be doing it.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.