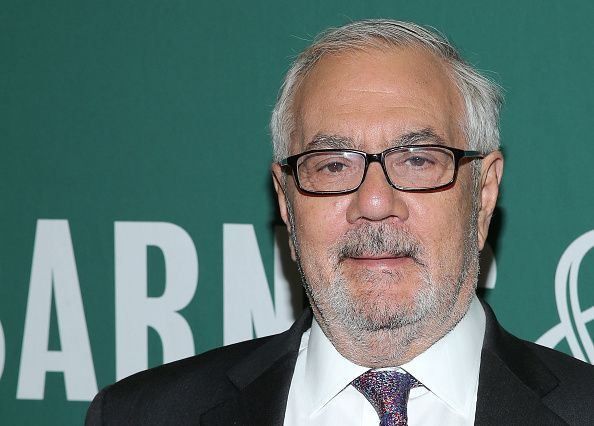

Wall Street Money: Barney Frank To Oversee Democratic Platform While Running Big Bank

The past few months of national politics have been dominated by speculation that the Republican National Convention could turn ugly. It now appears the Democrats are headed toward their own version of convention conflict.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who has run an unexpectedly tough campaign against former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, wrote a letter Friday to the Democratic National Committee urging it to play fair when choosing the standing committees that will determine the rules and platform for the party. Sanders said in the letter that two appointees who had already been named are “aggressive attack surrogates on the campaign trail” for Clinton, including former Massachusetts Rep. Barney Frank — who sits on the board of directors of a major bank that was recently named in a lawsuit about an alleged Ponzi scheme. Frank has also publicly boasted about the money he has raked in from Wall Street, both as a lawmaker and now as a top Democratic Party power broker.

Frank's appointment could prove to be a hurdle for Sanders, who says he should be able to influence the Democrats' platform since he piled up a significant number of votes and won many states during the nominating season. One of the issues he is almost certain to push is Wall Street banking reform, which has been a cornerstone of his campaign message.

Frank sits on the board of Signature Bank, a 15-year-old bank that boasts $33 billion in assets and turned a record profit last year of $373 million. Of the $18,000 the bank donated to congressional candidates during Frank’s last election cycle, the Massachusetts lawmaker received $2,400, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics.

Investors filed suit against Signature this year after the company lost $66 million of investor cash in a scheme run by William Landberg, a money manager, who pleaded guilty to the crime in 2011. Investors allege that Signature helped Landberg by ordering him to shift money around dozens of accounts to cover up long-term overdrafts, according to the New York Times .

Between 1989 and his retirement in January 2013, Frank raked in more than $1 million worth of campaign donations from the securities and investment industry, according to CRP data. More than a third of that cash haul came during the 2010 election cycle, when Frank was involved in sculpting new Wall Street rules — which some critics including Sen. Sanders say did not go far enough to rein in the industry after the crisis.

In 2012, Frank told NPR that such donations inevitably influence those in position to wield political power.

"People say, 'Oh, it doesn't have any effect on me,'" he said at the time. "Well, if that were the case, we'd be the only human beings in the history of the world who on a regular basis took significant amounts of money from perfect strangers and made sure that it had no effect on our behavior."

In the months before his appointment to oversee the Democratic Party’s platform, Frank has touted all the money he accepted from the financial industry.

Of late, though, Frank has changed his tune. While promoting Clinton’s candidacy, he has called the Vermont senator “McCarthyite” for demanding Clinton release transcripts of her paid speeches to Wall Street groups. Frank has also started arguing that his own willingness to take finance industry cash was a good thing.

“Over a 40-year career in elected office, I not only took contributions from [the finance] industry, I requested them,” he wrote in Politico in December in a piece entitled “Yes, I Took Bank Money. And It Made Me a Better Regulator.”

“Since retiring three years ago, I have again not only accepted fees from financial companies and finance groups, but I’ve solicited opportunities to do so through my agents. I’ve also served for two years on the advisory board of First Alliance, a company that deals with residential mortgages.”

The former House member argued, “By demonizing finance-industry contributions, we’re effectively insisting that instead of 80 percent of the industry’s contributions going to opponents of regulation, it should be 95 percent or more. Is this money corrupting? In my own experience, it’s more reasonable to see it as a form of political self-defense unlikely to dilute their support for reform.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.