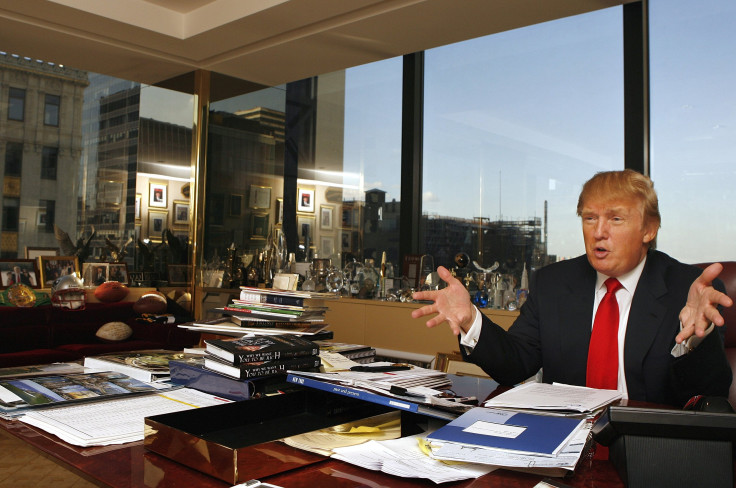

Will Donald Trump Have To Take His Name Off His Buildings To Comply With Conflict Of Interest Rules?

Congressman, senators, and high-level executive appointee are all required to disclose their financial interests, and recuse themselves from government business that could have an impact on their own bottom line. But no such restrictions exist for presidents — even those like President-elect Donald Trump, whose massive investments and financial interests could be affected by public policy.

The scope of Trump’s potential conflicts is vast. He owns stock in defense contractors; on the campaign trail, he vowed to increase the size of the US Navy. Trump Palace Condominiums, one of his subsidiary companies, leases to the federal government, meaning President Trump is poised to become his own company’s landlord. Trump also owes millions of dollars to Deutsche Bank — which is currently negotiating a fraud settlement with the Department of Justice, an agency which President Trump will oversee.

“There's a massive opportunity for corruption,” Andrew Stark, a professor at the University of Toronto and author of “Conflict of Interest in American Public Life,” told International Business Times. “To have a president in office whose judgment could be skewed — that's very, very disturbing.”

All other members of a Trump administration would be required to untangle themselves from these sorts of conflicts. Federal ethics laws make it a crime for any employee of the executive branch to participate “personally and substantially” in a matter where they have “a financial interest.” And the 1978 Ethics in Government Act, passed in the wake of the Watergate scandal, sets up strict disclosures requirements for officials and their families to ensure that conflicts aren't being hidden.

But in 1989, the Senate specifically exempted the president and vice president from any legal penalties that could arise from a conflict of interests, as a way to shield President Ronald Reagan from a pending ethics investigation.

So, legally, all Trump is required to do is file a standard financial disclosure form from the U.S. Office of Government Ethics (OGE) to the Federal Election Comission. He filed his form back in 2015. On the campaign trail, Trump repeatedly deflected questions about his still-unreleased tax returns by pointing out that his OGE disclosure form is 104 pages long: “the largest in the history of the FEC,” he said at the time.

Filing the disclosure form is the extent of Trump's legal obligations: Most experts agree that what President-elect Trump does to extricate himself from his businesses is entirely up to him.

He has offered some vague hints at what he plans to do. “If I become president, I couldn’t care less about my company. It’s peanuts,” Trump said during a debate with Hillary Clinton in January. “Run the company, kids. Have a good time.”

Trevor Potter, former head of the Federal Election Commission, is skeptical that such an arrangement — while legal — would do anything to minimize conflicts. "If his daughter or his son-in-law turns up in a foreign capital to negotiate a business deal on behalf of the Trump business, that foreign government is going to certainly think they're doing business with the family of the president of the United States, which indeed they will be," Potter told NPR.

Stark agreed that ethical questions wouldn't disappear if Trump simply turned over control of his business. “The laws and regulations don't draw a distintion between him and his kids,” he said.

Presidents typically placed their assets in a blind-trust, to avoid the appearance of conflicts. Jimmy Carter put his peanut farm in a trust when he won the 1976 election. Avoiding conflicts doesn’t have to be a major financial burden: In 1989, Congress added a provision in the U.S. tax code that allows members of the executive branch to sell off their assets and avoid capital gains taxes, to shed any conflicting investments.

Since winning the election earlier this week, Trump has not commented on his plan for the Trump Organization, its billions of dollars of assets spread over the globe, or the hundreds of smaller companies, building, hotels, and casinos that bear his name.

But those Trump-branded properties could provide a way for regulators to pierce the presidential immunity from conflicts laws. The 1989 Ethics Reform Act, Stark says, prohibits any senior “non-career” government “officer” from having their name “used” by any firm involved in fiduciary arrangements. The law was intended to require a would-be president to remove his or her name from a law firm or real-estate partnership while serving in office. But in Trump’s case it could have far-reaching consequences: 264 subsidiary companies owned by the Trump organization bear his name, another 54 include his initials.

“This sort of massive wealth was never anticipated by regulators,” Stark says.

There’s one catch: A rule issued by the Office of Government Ethics in 1991 exempted the president and vice president from the category “officer,” blocking enforcement of the use-of-name ban. But, according to Stark, all it would take to open up Trump to a wide-ranging conflicts probe would be to tweak the OGE’s rules and define the president as an “officer” of the government.

The current head of OGE is Walter M. Shaub, Jr., a career government lawyer who is an Obama appointee. Shaub's five-year term will end next year. President-elect Trump will then appoint a succesor, who will be subject to senate confirmation.

The OGE did not immediatly respond to request for comment on the use-of-name rule.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.