Pope Francis Climate Change Encyclical: Divided Catholics, Church Hierarchy May Challenge Environmental Call In US

Pope Francis’ highly anticipated encyclical on the environment will be released Thursday, and in the U.S. -- the world's fourth-largest Catholic nation, with almost 80 million baptized people -- it will reach a public sharply divided on climate change. The pontiff’s attempt to shift public discussion on the need for urgent climate action, in what may become one of the signature issues of his papacy, will not only have to persuade skeptics among the Catholic faithful but will also face the challenge of swaying a church hierarchy largely resistant to his progressive message.

As one of the most anticipated encyclicals ever, Francis’ “Laudato Sii" (“Praise Be to You”) will get a lot of attention from the church faithful, but it might not necessarily herald a massive shift in Catholic public opinion about climate change, according to Bill Portier, a professor of Catholic theology at the University of Dayton. “Whatever culture war side you're on in this argument is going to have a whole lot to do with how you receive what the encyclical teaches,” he said.

Based on an unofficial draft of the document leaked Tuesday, the 191-page encyclical is expected to attribute climate change to human activity, while calling on Catholics and non-Catholics alike to take urgent action to address what it calls one of the most important moral issues facing society. “Numerous scientific studies indicate that the greater part of the global warming in recent decades is due to the great concentration of greenhouse gases … given off above all because of human activity,” read an excerpt of the draft, according to a translation by the Guardian.

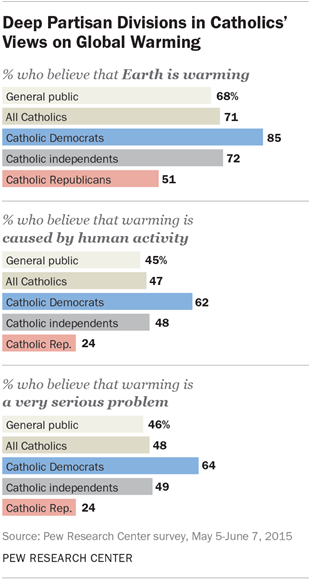

This message might not resonate with a broad swath of Catholics in the U.S., where skepticism toward the idea of climate change as a man-made phenomenon remains high. Reflecting a broader divide among the American public at large, Catholics are also largely split on the causes of climate change, according to a Pew survey released Tuesday in anticipation of the encyclical’s unveiling.

While about 71 percent of U.S. Catholics agree that the planet is getting warmer, just under half (47 percent) attribute the change to human causes. A similar share (48 percent) characterize the issue as a serious problem. The divide between Catholics on the issue falls largely on partisan lines, with 62 percent of Catholic Democrats saying they believed that the earth's warming is caused by human activity, compared with 24 percent of Catholic Republicans.

The impact of Francis’ encyclical on U.S. Catholic opinion is difficult to predict, said Jessica Martinez, a research associate at the Pew Research Center and one of the study’s authors. However, the broad support across partisan lines for Francis -- the pontiff has a net favorability rating of 89 percent and 90 percent among Democrats and Republicans, respectively -- raises the question of how his personal popularity could shift opinions on the issue. “It's something we'll have to keep an eye on as people become more familiar with what's in the encyclical,” Martinez said.

The pope’s emphasis on the issue will undoubtedly prompt soul-searching for some traditional Catholics. “People who have long grown accustomed to calling themselves good Catholics are going to be discomfited by this encyclical,” said the Rev. James Bretzke, a professor of moral theology at Boston College. “It shows that to be ‘a good Catholic’ is more complex than being against same-sex marriage and abortion.”

It’s already clear that the encyclical is proving uncomfortable for some prominent U.S. Catholic conservatives. Most notable among these figures is Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum, the former Pennsylvania senator who objected to the pope’s engagement with the issue in the first place. “The church has gotten it wrong a few times on science, and I think we probably are better off leaving science to the scientists and focusing on what we’re good at, which is theology and morality,” Santorum told a Philadelphia radio station earlier this month. The majority of Republicans in Congress reject the idea of man-made climate change and have politically opposed measures to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite the public heel-digging by figures like Santorum, there is some precedent to suggest that the pope’s encyclical could help catalyze a shift in Catholic opinions on the issue, according to Portier, who pointed to John Paul II’s encyclical about capital punishment. The 1995 letter, known as "Evangelium Vitae" ("Gospel of Life") can be traced as a source of the significant drop in U.S. Catholic support for the death penalty from 70 percent or more in the 1990s to just 53 percent in 2015.

However, even if the encyclical is successful in swaying public opinion about climate change, there will likely still be a significant gap between the Catholic flock's take on the issue and that of the church’s hierarchy. “American bishops are going to have to play catch-up,” said Bretzke. “There’s going to be a disconnect between some of the leadership of the church and the people in the pews.”

Where culture wars around abortion, artificial contraception and same-sex marriage once dominated the church’s social agenda, Francis has chosen to instead emphasize climate change and broader issues of poverty and inequality -- a move that has been met with some resistance from the traditionally conservative church leadership. Most current American Catholic bishops were appointed and influenced by Francis’ predecessors, Benedict XVI and John Paul II, both of whom took far more conservative approaches -- in public -- to social issues than the current pontiff.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has been slow to adopt Francis’ social agenda, highlighted most recently by last week’s conference of the body in St. Louis, when only 40 out of 250 bishops at the meeting attended a workshop on the climate change encyclical. “Climate change isn’t the sort of thing [bishops] would have learned in the seminary or through their course of study or basic administration,” said Bretzke. “If only 40 found it worth their time to attend, that does say something.”

The conference also unveiled its priorities for 2017 to 2020, a list that the New York Times called “essentially a replay of its pre-Francis agenda,” with its focus on opposition to same-sex marriage, abortion and euthanasia. However, some bishops openly voiced their objections to the agenda, arguing that poverty needed to be a top priority. Archbishop Joseph W. Tobin of Indianapolis said that the list failed to reflect “the newness” and “dynamism” promoted by Francis, urging that the priorities be reworked “so it’s clear that we take him seriously and we’re accepting his pastoral guidance,” the Times reported.

This response is an encouraging one, said Bretzke, who argued that the release of the encyclical will only embolden such voices and give them greater credibility. “This is the Francis effect, because before they never would have said this publicly.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.