What Are Pheromones And Will They Get You A Date On Valentine's Day?

In the 1970s a slew of perfumes were marketed with the word "pheromone" either on the bottle or in the ad. The idea behind the labeling was that you could magically bottle sex chemicals that made you irresistible to others. This concept was parodied in a scene in "Anchorman" when Brian Fantana (Paul Rudd) decides to "musk it up" by applying Sex Panther, a cologne that stung the nostrils, according to Ron Burgundy (Will Ferrell), "but in a good way."

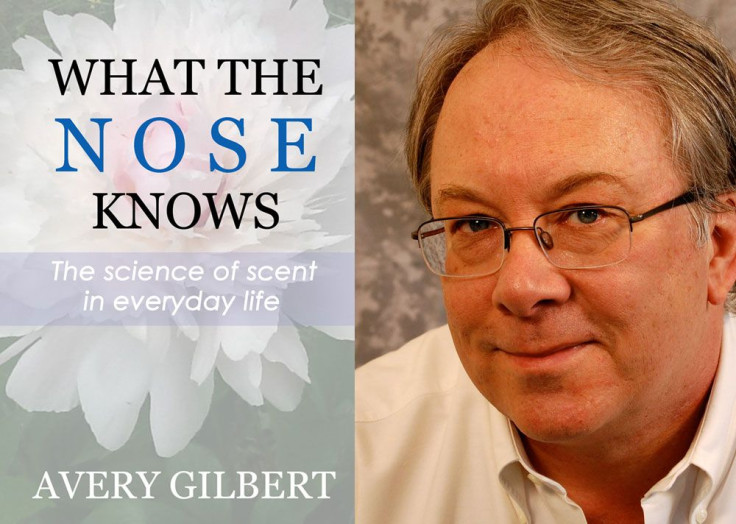

Scent scientist Avery Gilbert, author of What the Nose Knows: The Science of Scent in Everyday Life, talked to International Business Times about what pheromones are, what the biggest myths are about pheromones and what role scent plays in attraction between people.

International Business Times: How did you become a scent scientist? Tell us about what you do and what your projects are.

Avery Gilbert: My original interest was animal behavior and that involves a lot of smell—marking territory, recognizing kin, avoiding predators, etc. As a post-doc I studied how mice choose mates based on body odor. I did a side experiment that proved humans can smell the difference between strains of mice differing only in one gene. After that I turned exclusively to the human sense of smell. I worked for a fragrance company and eventually set up my own consulting business. Today, I help companies design scented products and integrate scent into marketing, brand awareness and new technology.

IBTimes: What are pheromones? Do animals and humans have them? What's their function?

A.G.: Strictly speaking, a pheromone is a molecule released by one organism that triggers an automatic, reflex-like behavior in another member of the species. Insects are the original and still best example. Dip a swizzle stick in sex pheromone and a male cockroach will try to mate with it. Pheromones are found in mammals like pigs, hamsters and horses. The evidence is a lot shakier when you look at primates and not very convincing when it comes to humans.

That said, humans' body odors carry all sorts of information, including sex, age, sexual maturity, emotional state and various cues about health. We all broadcast this information and we also respond to it, although we are not always aware of doing so. I think body odor is involved in sexual attraction, mother-infant bonding and much else we do, like how we react to our boss or what we think of the person next to us on the subway.

IBTimes: What are the biggest misconceptions about pheromones? We know that perfumes/colognes in the 1960s and 1970s liked to hype musk and pheromones, suggesting that you could just bottle this stuff and -- boom! -- people would swarm. Like Axe commercials today. Clearly it's a fantasy.

A.G.: Believe it or not, the Axe Effect -- ladies throwing themselves at a good-smelling guy -- is true to the original concept of insect sex pheromones. In theory, I should be able to open a vial of human sex pheromone on the M train at Canal Street and have an orgy going by time it gets to Williamsburg. Which reminds me, my favorite pheromone story is “Bitch” by Roald Dahl.

The biggest problem with pheromones is that the concept is applied to everything and thus explains nothing. For example, it used to refer to simple, automatic behaviors, but now it’s used to explain preference ratings for facial photographs. It used to mean a specific chemical or blend of a few chemicals, but it now refers to any complex odor, like perfume. The concept has been stretched so far it’s almost meaningless. That’s why I no longer invoke pheromones, even though I’m a big believer in communication by human body odor.

IBTimes: Have you heard about these Pheromone Parties? What do you think of the premise, that you can pick the right partner from their body odor?

A.G.: The premise is almost right. Here’s a better version: pre-sniffing a person’s B.O. will help you reject an unsuitable partner. I hear “I liked him but not how he smelled” much more often than “He wasn’t interesting, but I dated him because he smelled good.” Attraction and repulsion are equally valid factors.

IBTimes: Does scent play a part in attraction? There are those studies about women who are on the Pill picking the wrong partners, or that the smell of male sweat can help regulate a woman's menstrual cycle. Any studies with fairly conclusive evidence that scientists don't sniff at suspiciously?

A.G.: When you like someone and you like how they smell, their scent powerfully reinforces the attraction. There may be short-term physiological effects as well. Men find a woman’s B.O. more attractive when she is in the fertile (follicular) phase of her cycle. And a man’s testosterone response to female B.O. depends on how far she is from ovulation. Not to mention that men tip ovulating strippers more generously, presumably based on a scent signal.

And yes, whether or not a woman is on the Pill when she selects a partner has downstream consequences for sexual satisfaction and other measures of relationship quality. Overall, I’d say the idea that scent has an impact on relationships is pretty well-established.

IBTimes: Are there particular scents that men love? Women? Are these culturally determined?

A.G.: What men and women love in a perfume is inseparable from the perceived masculinity or femininity of the person wearing it. People tend to regard certain smells as feminine (sweet florals, for example) and others as masculine (say, woody notes). Perfumes usually default to these sensory categories -- or very deliberately try to steer between them. Of course, a little bit of fragrance gender-bending can be exciting, but you need established categories in order to cross them.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.