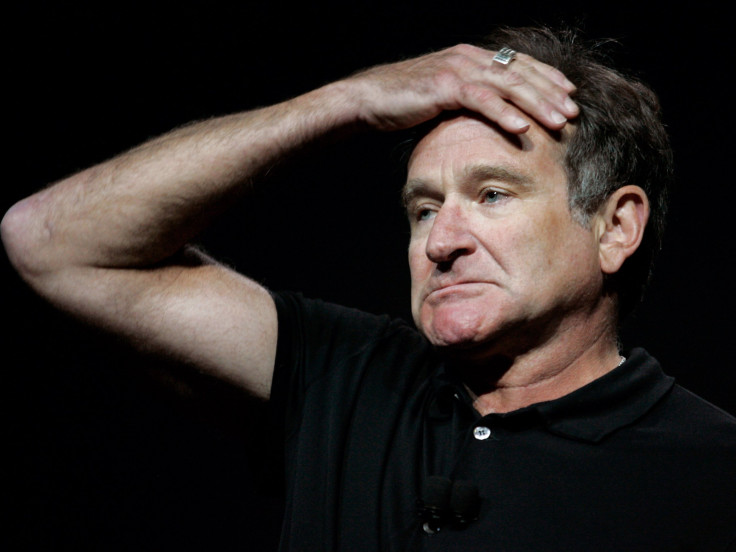

Robin Williams Depression: Comedy, Mental Illness Link Proves Fatal For Many Hollywood Stars

Sarah Silverman deals with it. John Belushi did too, and it’s thought to have inspired some of Peter Sellers’ best material. But Robin Williams’ death Monday, the official cause of which has yet to be determined, is another sad reminder that, for many of the famous comedians audiences have grown to adore, depression and mental illness are struggles that even millions of dollars and the highest reaches of fame can’t always help.

Williams, 63, was pronounced dead at 12:02 p.m. PDT Monday in his California home after a 40-year career that saw him star in dozens of the most beloved movies in cinema history. A master of improvisation, Williams first found fame on the “Mork & Mindy” television series before also embarking on a lauded standup comedy career. The shock of his suspected suicide, though, comes after a lifelong battle against addiction and depression that so many entertainers seem to struggle with during their time in the limelight.

According to a study published by British researchers in January, comedians are often able to make audiences laugh because of their unusual personalities. The survey, which examined 523 comedians, has been described as one of the first concrete pieces of evidence supporting the long-held notion that there’s some kind of link between creativity and mental instability.

“The creative elements needed to produce humor are strikingly similar to those characterizing the cognitive style of people with psychosis – both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,” said Professor Gordon Claridge from Oxford University’s department of psychology, as quoted by the Guardian.

“Although schizophrenic psychosis itself can be detrimental to humor, in its lesser form it can increase people’s ability to associate odd or unusual things or to think outside the box. Equally, manic thinking, which is common in people with bipolar disorder, may help people combine ideas to form new, original and humorous connections.”

The idea is not new. Charlie Chaplin, the famous silent film star who helped Americans laugh through the Great Depression, was said to have a brooding personality and spent much of his time off-screen in despair.

“There are days when contact with any human being makes me physically ill,” Chaplin told poet and journalist Benjamin De Casseres around the dissolution of the actor’s first of four marriages. “I am oppressed at such times and in such periods by what was known among the Romantics as world-weariness. I feel then a total stranger to life.”

De Casseres, whose time with Chaplin was highlighted in a Lapham’s Quarterly article, wrote that the star of “The Kid” and “The Great Dictator” was popular in every corner of the globe. Still, “there is no man I have ever met … whose stage personality is better known than any other human being who has thus far been born on this star and who has more completely hidden his real personality than any other world figure. I never met an unhappier or a shyer human being than this Charles Spencer Chaplin.”

Societal stigmas have reduced since Chaplin’s time, when crippling depression may have been dismissed as “world-weariness” and post-traumatic stress disorder (seen in World War I) was commonly referred to as “shell shock.” But, just as mental illness may have given performers a special and creative outlook on life, it’s also proven deadly.

Richard Pryor is believed to have struggled with bouts of depression exacerbated by a childhood in which he was molested, only learning to make people laugh to relieve the stress that came from living in a brothel. Pryor, like so many before and since, may have started taking drugs because of his mental state, eventually setting himself on fire and living to tell the story in “Live on the Sunset Strip.”

“My dad was a very scared, closed person,” Rain Pryor, Richard’s daughter, told People magazine in 1995. “Dad spent most of my childhood locked away in his room with his women and his drugs. He lived in his own reality. He trusted no one.”

John Belushi, the “Saturday Night Live” and “Animal House” star, died in 1982 of a drug overdose that his wife believed was the result of a lifelong fear of being alone. Williams, a friend of Belushi’s, said in 1991 that it was this event that inspired him to quit drinking and doing cocaine.

“It was a strange thing because my managers sent me to this doctor because they said I had this cocaine problem,” Williams told the Los Angeles Times. “That was before they’d started to acknowledge it was psychologically addicting. And then at a certain point you realize, maybe it is. Physically I’m not craving it, but mentally I’m really thinking it might be a good idea.”

Aside from a few interviews, though, Williams largely kept quiet about his struggle, once saying in an NPR radio interview that he was never diagnosed with clinical depression or bipolar disorder. (A representative told Entertainment Weekly Williams “has been battling severe depression of late.”)

“Do I perform sometimes in a manic style? Yes. Am I manic all the time? No. Do I get sad? Oh yeah,” Williams told "Fresh Air" host Terry Gross in 2006. “No clinical depression, no. I get bummed, like I think a lot of us do at certain times.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.