Secret To Owl's Head-Turning Success Revealed: Why They Don't Break Their Necks

Owls are able to rotate their heads a full 270 degrees -- a feat that has puzzled many researchers for years. This adaptation is key to the owl’s vision, since its eyes are fixed in their sockets. Without that flexibility, an owl would be stuck with quasi-tunnel vision.

When seen in real life, it looks like something alien or from a horror movie:

But if a human tried to attempt such a move, he’d cut off the blood supply to his brain.

“Brain imaging specialists like me who deal with human injuries caused by trauma to arteries in the head and neck have always been puzzled as to why rapid, twisting head movements did not leave thousands of owls lying dead on the forest floor from stroke," senior investigator and Johns Hopkins University neuroradiologist Philippe Gailloud said in a statement Thursday.

Gailloud and his colleagues think they’ve unraveled the secret to owls’ head-turning success, and it turns out that an owl has special adaptations to both its neck vertebrae and the blood vessels leading to its brain. A poster detailing the team’s findings featured in the latest issue of the journal Science won first prize in the National Science Foundation's 2012 International Science & Engineering Visualization Challenge.

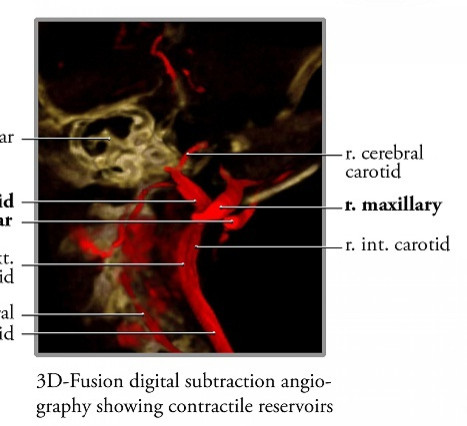

The researchers injected dye into owl arteries to illuminate the blood vessels in X-ray scans and mimic blood flow. When the birds’ heads were manually turned, the researchers noticed that the blood vessels near the jaw bone, at the base of the head, ballooned as the dye entered, creating a blood reservoir. These reservoirs allow the owl to keep a pool of blood handy to supply its brains and eyes while its head is turned, the researchers say.

Gailloud says the results “show precisely what morphological adaptations are needed to handle such head gyrations and why humans are so vulnerable to osteopathic injury from chiropractic therapy. Extreme manipulations of the human head are really dangerous, because we lack so many of the vessel-protecting features seen in owls."

Like many other birds, the carotid arteries in an owl are also located near the center of the bird’s neck, rather than on the side like in humans, thus minimizing the amount of torque the vessel experiences during a head turn.

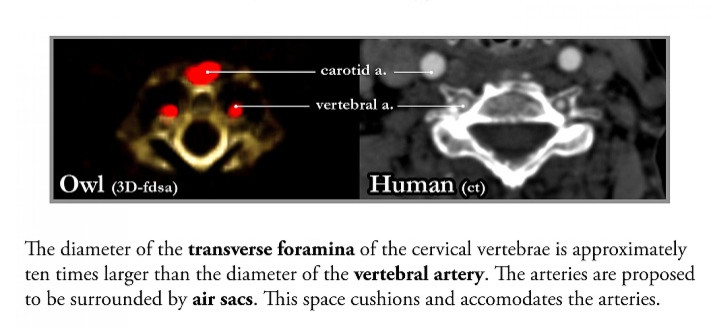

Another feature the researchers found in the owl’s neck are extra-wide cavities in the vertebrae, where major arteries are threaded up to the brain. That extra space allows the artery to move around much more easily when the owl twists its neck.

"In humans, the vertebral artery really hugs the hollow cavities in the neck. But this is not the case in owls, whose structures are specially adapted to allow for greater arterial flexibility and movement," Fabian de Kok-Mercado, a former Johns Hopkins grad student and medical illustrator, now with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, said in a statement Thursday.

Owls also turn out to have little connections, dubbed “anastomoses,” between their carotid and vertebral arteries that allow the two vessels to exchange blood. That way, if one major route to the brain is blocked when the bird twists its head, blood can travel up the alternative artery.

“You would have thought we knew everything there was to know about the owl. A lot of this is down to technology, which allows us to break new ground,” de Kok-Mercado told the BBC on Friday.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.