'Shawshank Escapees': Why Joyce Mitchell Aided Dannemora Convicts; Interview With 'Women Who Love Men Who Kill' Author

The investigation deepens into the role that Dannemora prison worker Joyce Mitchell, 51, had in aiding the escape of Richard Matt and David Sweat seven days ago. Mitchell, an industrial training supervisor at the upstate facility, gave hacksaw blades, drill bits and lighted eyeglasses to Matt and Sweat that officials say helped them make their daring breakout last Saturday, sources told CNN. This adds to speculation that Mitchell had planned to be the getaway driver for the escapees -- dubbed the "Shawshank escapees" due to comparisons with the plot of "The Shawshank Redemption" -- but backed out. Mitchell told officials that Matt, in particular, "made her feel special."

The convicts were still at large as of Friday afternoon.

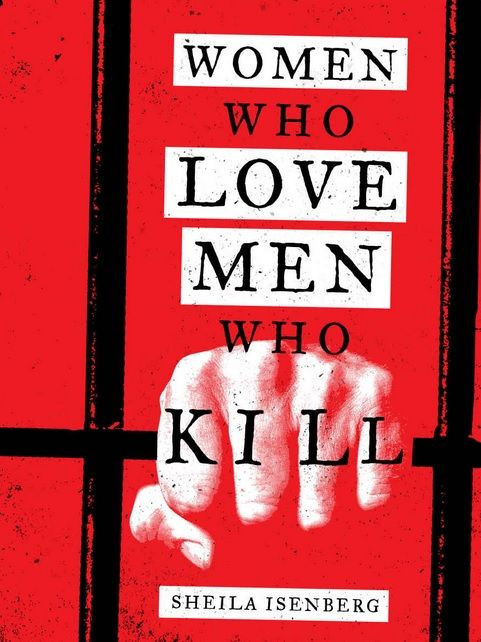

Sheila Isenberg, author of the groundbreaking 1991 book "Women Who Love Men Who Kill, spoke with International Business Times about why Mitchell would risk everything to help convicted killers. In her book, she interviewed dozens of women both inside and outside prison who fell for prisoners. Isenberg discussed the typical profile of women who fall for criminals, what might motivate them, and whether or not she thinks of them as victims.

International Business Times: How did you get interested in writing a book about women who fall in love with convicted killers?

Sheila Isenberg: Back in the early '90s, a New York stockbroker was going on trial for the murder of his second wife. In the stories about it, they had pictures of him in the newspaper, and standing next to him was an attractive young woman labeled as his fiancée. And I thought, why is she engaged to this guy? I was a press secretary, and it got me thinking, and there were other cases I knew of, so I started doing research and that was the beginning of this book.

IBTimes: What's the most shocking story you heard of the women you interviewed?

Isenberg: There was a woman on the jury who convicted a murderer, and she went and visited him and ended up in a relationship with him. There's a story that happened after the book was published, about a young woman who got into a relationship with a man who murdered her grandmother. They're all shocking.

IBTimes: What's the typical profile of a woman who falls for these killers?

Isenberg: Chapter 6 of "Women Who Love Men Who Kill" is a summary of what I found. I interviewed three-dozen women and when I went into it I had no idea the answer. I think I have an answer: They have certain things in common. All of the women I interviewed -- I have a journalist background, I'm not a scientist -- but they'd all been abused in their childhoods: by their fathers, their parents, some of them sexually, most of them physically, all of them psychologically. A lot of them had been victims of domestic violence from their first marriages.

These are women who had been victims of abuse. So when they got into a relationship with a prisoner in prison for life or death row, even though it sounds weird, he was a safe relationship because they couldn't hurt them. Another thing they had in common, of the women I interviewed, they were all Catholic.

IBTimes: What do you make of that? The first thing that jumps to my mind is that there's a belief in redemption and the idea that people can be saved.

Isenberg: I don't think so. A lot of people who see this phenomenon think that women who go into this thinking they can save, redeem and change the guy, but what I found is that they don't see him as someone bad who has to be redeemed. They see him as a changed person, as not bad. If he killed my grandmother, they might say, he was young and foolish, he didn't know what he was doing. Now he's a different man. All of the women I interviewed had incredible excuses for the men who murdered: He was young, he was on drugs, his friends made him do it, he didn't mean to pull the trigger. There was one woman who claimed that in the convenience store where a man shot someone, it was because the door banged into his arm holding the gun.

Carol Ann Bundy, who married serial killer Ted Bundy, believed in his innocence even after he was convicted. And she had a child with him. But then she realized he was guilty and ended the realtionship. Same with the woman who got involved with John Wayne Gacy; she believed he was innocent even though he was convicted of murdering 33 young boys and men. And she was in a relationship with him until she realized he was guilty.

As for Joyce Mitchell, I'm not sure which guy she was involved with -- the good-looking tall dark one or the young blond one -- but whoever it was, she's convinced that he's not bad. He shouldn't be there. Maybe he did the murder but he didn't mean to do it. That kind of thing.

IBTimes: Did psychologists or psychiatrists you interviewed have a theory for why, out of the pool of available men, these women would choose imprisoned killers?

Isenberg: Back when I wrote the book, no one knew about this phenomenon. One guy John Money coined hybristophilia [a paraphilia for criminals, particularly who commit cruel or outrageous crimes] and wrote extensively about it. He wrote about the philia of people who get off on violent criminals. There may have been some of that in these women. I didn't find that. What I found was, these women were angry with their abusers, they didn't do anything about it. These men committed murders. So maybe they had acted on the anger the women felt. I don't know. I'm not a psychologist. There were other theories: Women are attracted to bad boys, the redemption theory, hybristophilia. I don't agree with any of them.

IBTimes: Did the women you interviewed tell you what they hoped would happen at the end of these relationships?

Isenberg: They hoped to get them out of prison. And they hoped that they would live happily ever after. What the relationships had in common, more so than the women, was the unnatural elements of the relationships. They didn't happen in the real world, in real time. It has a fantasy element to it. They were romantic, artificial, with prison guards, walls, all that. The men don't have jobs, careers, kids, families. They didn't have anything to take them away from this courtly, worshipful love they could shower on the women. So it's a fantasized, romanticized "love."

All of the women bought into it. They'd say, "I fell in love. My heart stood still. I was swept away. I couldn't control my feelings." All those things that you feel and say when you fall into what I call stage one love. When you're swept away by physical attraction. And in a normal relationship, it changes. It becomes what psychologists call companionate love. It never gets there in these relationships. It stays in the roller coaster, excitement, thrills stage.

IBTimes: Would you characterize these women as victims of the murderers?

Isenberg: The men definitely conned them. They're called convicts. They lie, trick and manipulate them. So in that sense, they're victims, but they're also not victims in the sense that they're actors in their own fate. They had their own need to achieve thrills in their lives and try to be in a relationship where they can have some control. Even though the ultimate goal is to get the guy out of prison, the whole time they're in the relationship, the men are in prison. They [the women] have all the control. It's complicated. I try to point out in the book that the women aren't crazy. It's like when you look at your best girlfriend and say, what does she see in that guy?

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.