SodaStream Boycott: At West Bank Factory, Palestinian Workers Reveal What They Think About Their Employer

MISHOR ADUMIM, West Bank -- The large, nondescript factory painted in blue and pink with splashes of orange, nestled in the Judean Hills, is a world away from flashy Super Bowl commercials and Hollywood actress Scarlett Johansson. But this past week, SodaStream's production plant in the Israeli-occupied West Bank -- and its Palestinian workers -- have been thrust dramatically into the media spotlight, igniting an international controversy.

An Israeli company listed on Wall Street, and the world’s biggest maker of home-carbonation machines, SodaStream International Ltd (NASDAQ:SODA) has 22 manufacturing facilities around the world, including this one. For 17 years, its factory in Mishor Adumim, part of the largest Jewish settlement in the area near East Jerusalem, has slipped under the radar with little attention.

But SodaStream has become the target of activists affiliated with the international Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, a long-running campaign to isolate Israel’s economy until it withdraws from the occupied West Bank. The controversy caused a rift between Johansson, who signed a sponsorship deal with SodaStream, and British charity Oxfam, which opposes trade involving Israeli settlements, eventually leading the actress to quit her role as a spokeswoman at Oxfam after eight years. She starred in a commercial for SodaStream that aired during the Super Bowl on Sunday.

Johansson, who has a Jewish mother, has not visited the factory in Mishor Adumim, nor been to the Israeli-occupied West Bank. She offered a different view of the factory, saying it employed both Palestinian and Israeli workers on equal pay, and described it as a rare opportunity to build “a bridge to peace” between the two. Of the 1,300 people employed at the Mishor Adumim factory, 500 are Palestinian from the Occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, 450 are Arab citizens of Israel and 350 are Jewish Israeli.

Meanwhile, Palestinians who work at the factory tell the International Business Times that they are just trying to make a living.

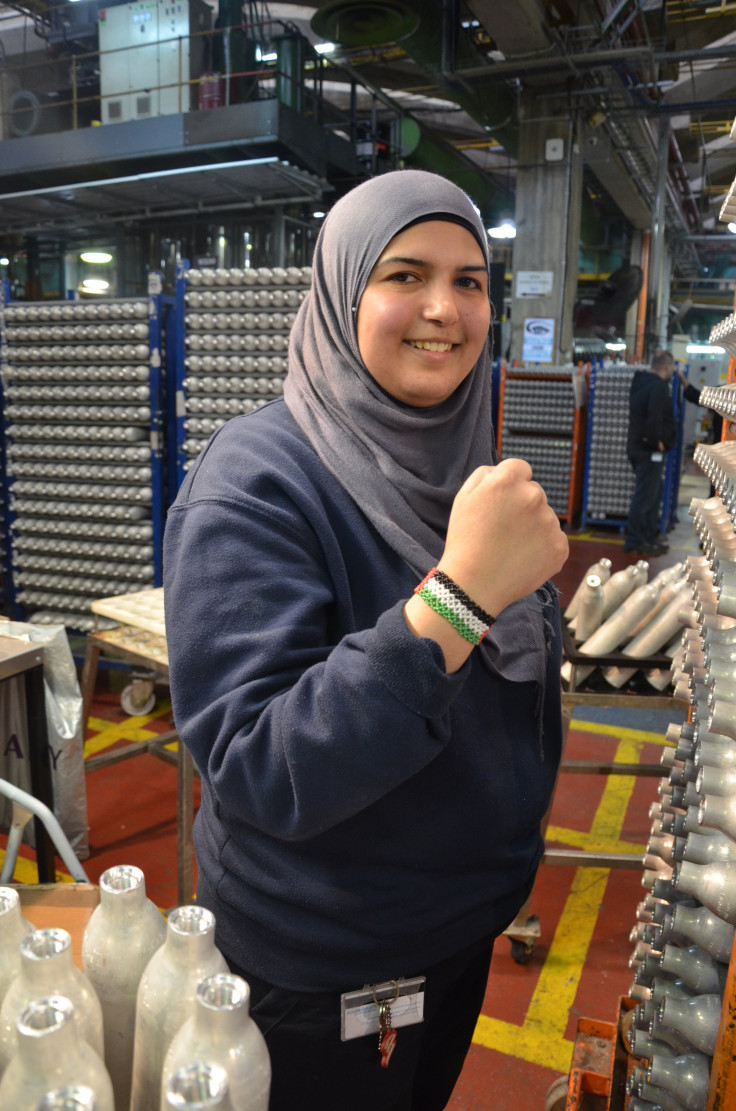

Yasmin Abu Markhia, 22, is proudly Palestinian. When asked about her nationality, she lifted her sleeve to show a Palestinian-flag bracelet.

Abu Markhia checks and stacks the carbon dioxide canisters that go inside SodaStream machines. She has worked at the factory for just four months. Considering she's a Palestinian living in Jerusalem but working in the occupied West Bank, the political storm is far from her mind. She said she sees no conflict in working at SodaStream: “We are human, we earn good money and the work is good.”

Zafid Abu Aballah, 28, is an Israeli Arab who has been a machine operator at the factory for four years. He earns $2,000 a month, significantly more than the Palestinian Authority minimum wage of 1,450 Israeli shekels ($377).

“I have an Israeli passport. If the firm closed I could find another job, but Palestinians would not be able to. There are no jobs for Palestinians in the West Bank,” he said. “This is political, but the people here just want to work and live, they don’t have an interest in the politics between Palestine and Israel.”

Palestinian Nabil Basharat, 40, from a village near Ramallah, has worked for SodaStream for four years and is now a shift manager. He supports his wife and six children on an income he says is high by both Palestinian and Israeli standards. About the boycott, he said it came down to protecting the workers’ ability to earn a fair wage:

“We understand their [BDS and Oxfam’s] opinion, but they need to understand what the factory gives the Palestinian workers, and there are a lot of factories in this area doing the same thing.”

Similarly Palestinian Asharaf Aballi, 28, from Jenin, said he supported his parents, his wife and another eight family members on his income of $2,000: “First off we need a job and an income to live -- I have a family and I need money.”

An unemployed youth near Qalandiya checkpoint, who gave his name as Yasser, said the minimum wage in the Palestinian Authority made it nearly impossible to live. “We need more factories like SodaStream. It’s hard to get a job there,” he said.

SodaStream CEO Daniel Birnbaum told IBTimes on Monday that he is “fed up” with the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and that businesspeople should take the opportunity to contribute to peace. He also said he didn’t agree with settlements and believes that they shouldn’t be built, despite the fact that his factory sits in the center of one. His company can in fact be “a model for peace.” “We are showing Israelis and Palestinians that there can be peace,” Birnbaum said.

Birnbaum does not think he’s lost any customers because of boycott action. “If eventually there was a boycott, I don’t really care that much from a SodaStream standpoint, we’d just shift production to a different factory.”

Sodastream says it has manufacturing facilities in Israel, Germany, Sweden, the U.S., Australia, China and South Africa, besides the one in the West Bank. “Markets like Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Norway only receive products from outside this factory, from the mother of human rights -- China,” Birnbaum said sarcastically. Norway, Sweden and Finland have boycotted SodaStream products from the Mishor Adumim factory.

SodaStream has made a profit over the last two years and says it’s on track to show a 30 percent increase in profit over its June 2012 result, but it’s facing a rough start this year. Its shares on the Nasdaq have tumbled 26 percent in January and the company has issued a profit warning for the fourth quarter of 2013, with a net income of $41.5 million, citing “several factors,” which didn't include the international boycott.

As for the Johansson flap, “I frankly didn’t expect it to be as big a deal as it ended up being. I didn’t expect Oxfam to be so superficial in its treatment of this,” Birnbaum said.

Alun McDonald, an Oxfam spokesman in Israel and the Occupied West Bank said that the charity does not oppose Israeli-owned factories in the West Bank -- once a peace agreement had been reached.

“The problem at the moment is it’s in an illegal settlement on occupied land. If it’s an Israeli factory in a future Palestinian state, paying tax in Palestine and genuinely benefiting the economy, then it could be a good thing. Our opposition is not that it’s an Israeli company -- our position is the same for any company from any country working in settlements,” McDonald said.

“We believe Israeli settlements in the West Bank, are an obstacle to the chance of achieving a two-state solution and lasting peace and that presence and expansion of settlements is one of the main drivers of poverty in the Palestinian communities we work in,” he added. “Any company located in settlements contributes to their viability and legitimizes them, no matter what their labor practices.”

Sodastream was able to set up a factory in Mishor Adumim because it’s in Area C, the zone of Israeli-controlled land that makes up 61 per cent of the West Bank, per the Oslo Accords. Palestinians are prohibited from building on the majority of Area C. A World Bank report last year estimated that the Palestinian economy could be boosted by 35 percent if development of Area C were allowed.

For now, the SodaStream bottles and carbonation machines made here reflect the uncertain status of this occupied land, neither part of Israel proper nor of a still-to-come Palestinian state. Their labels don’t say “made in Palestine” on the label, nor do they mention the West Bank. “There is no nationality for customs purposes called Palestine, or the West Bank,” Birnbaum said. On the labels, depending on the destination market, SodaStream products “say either nothing, or made in Israel. … But they will always have the correct zip code. We’re not hiding what we’re doing.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.