Southwest, Great Plains States Are Ill-Prepared For Megadroughts This Century

Jack Castro worries about running out of water. As the city manager of Huron, a tiny farming town near Fresno, California, he’s struggling to find enough water to keep the taps flowing. The region has been slammed by a four-year drought, and Huron’s nearby reservoir supplies are steadily shrinking. Castro can purchase well water from farmers, but only at an exorbitant rate.

“We’re in limbo here trying to figure out what’s going to happen,” Castro says. “It’s going to be worse this year than last year.”

The drought is also crippling the local economy. Most of Huron’s 14,000 permanent and migrant residents depend on the cotton, pistachio, watermelon, garlic and tomato crops for work, but those are disappearing. Across the state, agricultural production dropped by 5 percent last year.

“People are moving out of the town. It’s very hard to see people around these days,” Castro says.

For Huron and towns around California’s Central Valley, the drought might be just a short-term crisis. But in the coming decades, crop shortages and water scarcity -- or worse -- could become the norm due to “megadroughts,” U.S. scientists say. The multi-decade, superhot droughts are projected to batter the American Southwest and Great Plains regions in the second half of this century -- that is, unless the U.S. and other countries dramatically reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, according to a NASA study released last week.

“Imagine the California drought lasting for 20 to 30 years,” Ben Cook, the study’s lead author and a climate scientist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City, says. “It’s going to be a real challenge to deal with, considering the problems we’re having with drought now.”

Water scientists and policy experts say that governments and residents must start making sacrifices today in order for communities and economies to survive a world of extreme dryness. Farmers and cities must stop guzzling groundwater resources and ration the precious supplies over decades. Homeowners will have to give up grassy lawns for desert-appropriate landscapes.

“Even though we’re talking about [megadroughts] in 2070, or 2080, we really need to get planning for our water future now,” Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist and professor at the University of California, Irvine, says. “The infrastructure that we have now is in no way capable of dealing with the megadroughts that the study points to.”

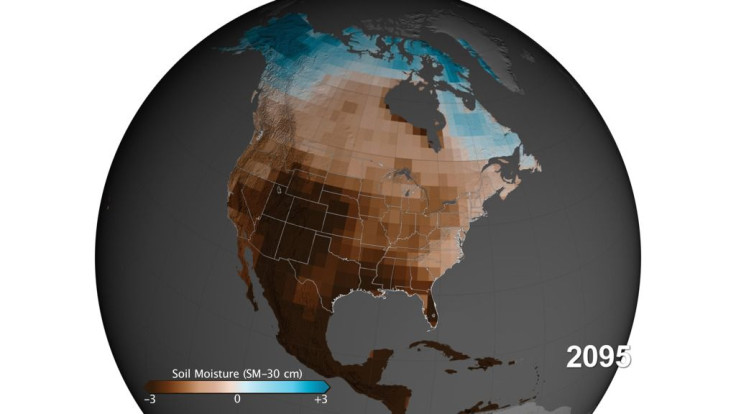

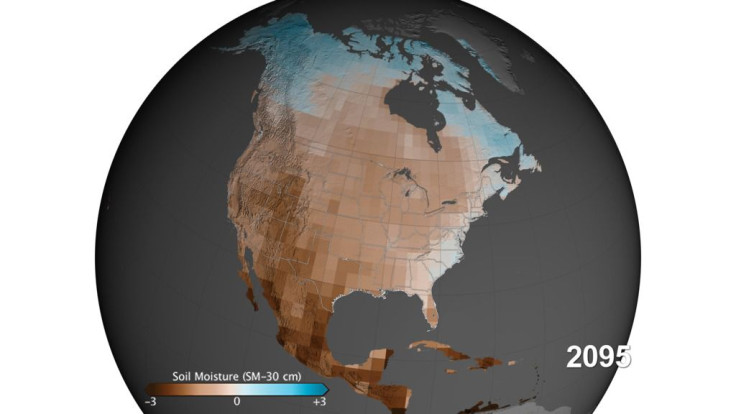

The NASA study combines centuries-old observational data on soil moisture and drought severity with projections on how increases in emissions could alter the planet’s climate. Scientists determined that if countries keep polluting at their current pace, the Southwest and Great Plains have an 80 percent chance of experiencing a decades-long megadrought between 2050 and 2099.

However, if nations aggressively curb emissions by replacing coal, oil and natural gas with cleaner alternatives and halting deforestation, the likelihood of megadroughts would drop to 60 percent, according to the study.

“As long as those [emissions] persist, these kinds of dry conditions will continue [indefinitely],” Jason Smerdon, a research professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and report co-author, says.

The scientists also compared future megadroughts to extreme dry periods in the past, such as the 1930s Dust Bowl that ravaged the Plains region. They found that the newer droughts would be much drier and endure far longer than anything seen in those regions in the past 1,000 years.

“What really makes megadroughts ‘mega’ is their persistence: the length of time that they last,” Smerdon says.

While historical and current droughts are largely caused by natural variations in the climate system, man-made global warming will be to blame for megadroughts. As global temperatures rise, the warmer air increases evaporation from the soil and transpiration from plants, which makes the land drier. While much of the United States and Mexico and parts of Canada will experience increased drying, the effects will likely be strongest in the Southwest and Great Plains states, which have historically suffered the most droughts.

The Southwest in particular could be hit by a “double whammy” of drying, Smerdon says. On top of decreasing ground moisture, precipitation levels will also decline, exacerbating the effects of hotter temperatures.

The Great Plains, by contrast, could see modest gains in precipitation levels, especially in more northern states like South Dakota. But the extra rain won’t be enough to overcome the dryness from soil and plants, he says. Megadroughts could deal a devastating blow to the region’s $92 billion agricultural sector, its economic backbone.

Nebraska in particular could lose up to 30 percent of its crops in the future due to drought and other climate-related events, the University of Nebraska at Lincoln found in a 2014 climate assessment. Loss in profits from falling production would force many family ranchers and farmers out of business, Jane Kleeb, a prominent climate activist and director of citizen advocacy group Bold Nebraska, says.

“There’s no way they can survive [that future],” she says.

Across the Great Plains, “in areas projected to be hotter and drier in the future, maintaining agriculture on marginal lands may become too costly,” according to the 2014 National Climate Assessment. “Climate change may thus result in a northward shift of crop and livestock production in the region.”

In many ways, states are already behind when it comes to preparing for megadroughts.

Californians, for instance, rely mainly on groundwater to irrigate crops and flush toilets now that the water in lakes and canals is vanishing. But underground aquifers can take thousands of years to replenish, and draining that water now could further strain communities in a hotter, drier future. Already states have guzzled 17 trillion gallons of groundwater from the Colorado Basin over the past decade due to population and agricultural growth.

“Even now we’re starting to see the southwestern U.S. is on a one-way trip toward eventual [groundwater] depletion -- unless we act aggressively to manage the resources,” Famiglietti, the UC Irvine hydrologist, says.

Up until a few months ago, California didn’t even measure its groundwater levels. Spurred by the extreme drought, the state in September enacted a law to protect its aquifers, which includes creating regional sustainability boards to closely monitor and regulate the systems. Famiglietti says a plan like this could have crucial benefits for the state, though he acknowledges it would take decades to fully implement. Protracted legal battles over local water rights could further ensnare its progress, he says.

States could further address drought by making extreme, and potentially painful, sacrifices in their water usage, Jay Lund, who directs the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California, Davis, says. In California, where half of urban water supplies go toward landscape irrigation, residents would have to get rid of their lawns almost entirely.

California farmers would also likely have to ditch “low-value” crops such as corn and wheat, which can be grown in other states, to save water for higher-value products such as almonds and wine. In a drier future, “a lot of the low value agricultural goes away entirely,” Lund says.

Cities across the region might have to adopt extensive wastewater recycling systems like the one in Orange County, California. The facility has pumped billions of gallons of purified wastewater into an underground aquifer since 2008, creating a continually replenished source of drinking water for the county’s 2.4 million residents.

Nebraska farmers, who suffered an excruciating drought in 2012, are starting to put sensors in their fields to help them see where they could reduce irrigation.

Kleeb says she hopes the megadrought study will serve as a wake-up call about the need to reduce emissions and prepare for dramatic changes to the climate. “One of the problems with climate change and drought is that people always think that it’s going to be this future act, and it’s not going to affect our families,” she says. “The reality is that we have to make changes now. There’s no other option.”

Lund says he's uncertain that the megadroughts described by NASA could actually happen, though he agrees that the region will experience hotter temperatures and drier conditions. “Looking back historically, it [a megadrought] is certainly a possibility, but I’d be surprised if it actually happens,” he says. “It’s just unlikely.”

In drought-stricken Huron, city manager Castro says he’s not concerned about future megadroughts. He doesn’t believe the science on global warming or that rising temperatures will make his town even drier. “That’s a different issue,” he says.

Even so, Castro agrees that Huron and other communities must do more to conserve water and reduce pollution in the oceans and from cars. Residents already cut their water use by 22 percent last year after the town adopted emergency restrictions.

“You have to do things the right way, in moderation. You can’t just abuse nature,” he says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.