Stories Of Families Who Decided To Have More Children, Despite China's Policy

Zhang Yimou, the famous Chinese director of "Curse of the Golden Flower" and "House of Flying Daggers," has caused uproar recently for having as many as seven children. However, Chinese families with more than one child are far from rare nowadays, more than 30 years since the one-child policy’s inception. These are stories, as recorded by Beijing Evening News, of ordinary people who wanted another child.

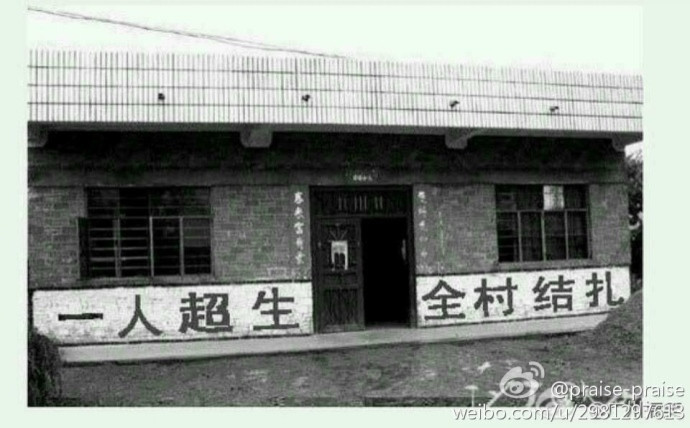

China’s one-child policy was first enacted in 1979. It specified that urban couples are only allowed one child. As a result, whole generations, beginning with those born in the 1980s, are growing up as the only child in their nuclear families.

A woman, who is only identified by her last name, Chen, walks a 3-year-old girl to nursery school every morning, and she introduces the girl as her niece. In reality, the little girl is her second-born child.

Both Chen and her husband love children, and they had one son previously.

“My son was lonely," she said. "Every time we asked, do you want a little brother or little sister, he would say happily, yes.”

It was just a joke at first, but Chen kept hearing from her son of kids in his nursery school with siblings. Many of her neighbors had more than one child, too. Chen and her husband finally decided to have one more while they still could.

“My husband has his own business, so my work unit would be the biggest obstacle,” Chen said. State-owned businesses, such as the one Chen works for, have very strict policies. If someone has more than one child, he or she gets fired and their superiors reprimanded.

“We looked into many options, including getting a disability certificate for our son,” Chen said. It is a common practice for couples who want another child, because the policy allows a second child if the first is disabled. But in the end this option was too risky for Chen.

Chen decided to have a doctor friend write an official diagnosis, stating that she has a chronic illness. With this, Chen was able to live in another city on sick leave while she was pregnant, and she gave birth to her daughter there.

“No one suspected anything, and even if they did, they wouldn’t report me,” Chen said. “Why would they mind other people’s business like that?”

After her daughter was born, the baby was taken to an aunt’s place for a year. After that, Chen took her daughter home, telling everyone she was her niece. Her daughter’s hukou, the required registration as a resident of the city, is actually in a suburb, because they could not get a city hukou for her legally.

“If my superiors find out and ask me to quit, it’s worth it for my daughter,” Chen said.

Rural Families Allowed More Children

Huang is a 34-year-old owner of a convenience store. In the last couple of days, all of his regular customers have congratulated him on his newborn son. This is his fourth child. His previous children, three daughters, are being raised by his parents in rural Hebei.

Huang, unlike Chen, is from a farming family and is allowed to have more children than the typical city-dweller. This is because it would be difficult for farmers to keep their farms alive without at least one son to take on the labor.

“Per the policy, if my first child is a girl, I could have another child, but my second born still turned out to be a daughter!” Huang said. “I didn’t want to give up, I wanted a son.”

Huang’s wife, during her third pregnancy, had to go to a different hiding spot every two weeks. She was always packed, ready to move when the planned birth bureau came around. Her third born was another daughter. Huang and his wife paid 5,000 yuan ($813.55) so the the couple could their daughters in Hebei and go to Beijing to earn money.

“The first couple of years in the city, we were too busy making a living," Huang said. "But lately, with the convenience store doing well, my wife got pregnant again.” Huang pointed to nearby businesses, including a liquor store, a Laundromat and a vegetable shop, and said, “their owners are from Hebei too, and they all had more than one child in Beijing.”

With a friend’s help, Huang’s wife gave birth in a privately owned hospital and spent only 4,000 yuan ($650.84). These hospitals don’t ask for any papers.

Since he was born illegally, Huang’s son won’t have a hukou in Beijing, but Huang is not worried.

“Some of my friends’ kids didn’t get hukous until they were four or five, we have lots of time,” he said. The important thing is, he finally has a son.

“All I need to think about is saving money for my son,” Huang said. He makes 80,000 yuan ($13,016) a year, and his family lives in a tiny one-bedroom apartment behind the store, according to Beijing Evening News.

“I’m not sending my son back to the countryside, I want him to attend schools in the city,” Huang said, his eyes full of dreams. “I will get money to support my son, no matter how hard it is.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.