Sub-Saharan Africa Lags Other Regions In Healthcare: World Bank, World Health Organization Report

More than 400 million people around the world don’t have access to essential health services, and many of them are in sub-Saharan Africa, where the resources are most needed, according to data from the World Bank and World Health Organization.

“The world’s most disadvantaged people are missing out on even the most basic services,” Dr. Marie-Paule Kieny, Assistant Director-General of Health Systems and Innovation at the World Health Organization, said in a Friday statement. “A commitment to equity is at the heart of universal health coverage. Health policies and programmes should focus on providing quality health services for the poorest people, women and children, people living in rural areas and those from minority groups.”

Their report on universal health coverage, released Friday, shows that while many countries have made incredible strides towards providing services to their population, low-income regions have a long way to go. Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, has fallen behind. And it’s a serious problem. The region bears 25 percent of the world’s disease burden but is home to just 3 percent of its doctors.

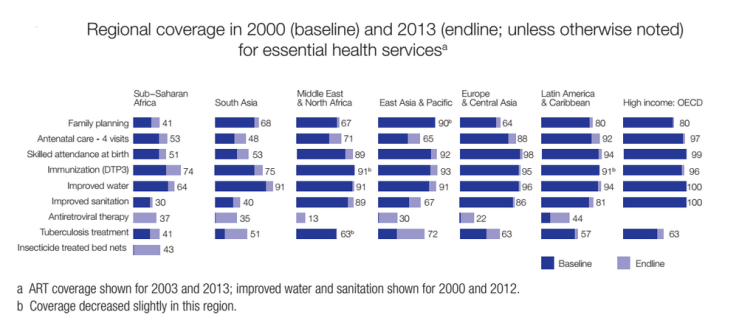

“Needless to say, poverty is a factor here,” the report says. “High-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries have high coverage rates across almost all essential services, while sub-Saharan Africa lags well behind other regions for several basic health services.”

Even within countries, more than 80 percent of women in the richest households have coverage while just 50 percent do in low-income families. While this has always been an issue, it was recently thrust into the limelight during the West African Ebola outbreak, which killed more than 11,000 people.

“Generally speaking, these problems are perceived as a steady rumble of dysfunction and discontent, but from time to time there is a spike in awareness regarding health system inadequacy,” the report reads. “The recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa is a case in point, the severity of the outbreak being in large part due to weak health systems, including a lack of capacity in surveillance and response.” Because of Ebola, basic services such treatment for common conditions, vaccinations and maternal health are at serious risk, and officials need to enact serious reforms to make this happen.

But while the Ebola virus captured international attention and sent medical researchers scrambling to find a cure, sub-Saharan Africa is also home a many diseases not experienced anywhere else that still don’t get attention.

A subset of illnesses known as neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) also continue to be overlooked, mainly for economic reasons. They are only a serious problem in some of the world’s poorest populations in tropical and subtropical regions.

“Lacking a strong political voice, people affected by NTDs are generally overlooked, while the lack of financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies has tended to discourage research and development in this area.”

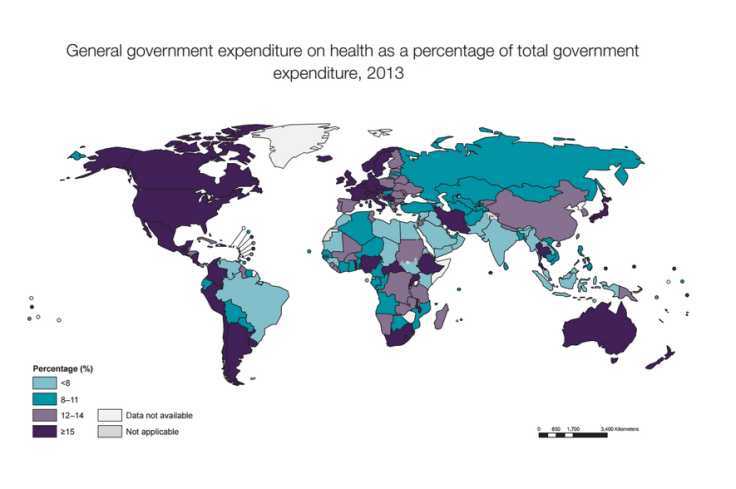

Meanwhile, the report found that many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have improved their healthcare spending but could do better. Though the region has experienced massive economic grown in recent yeras, each country spent, on average, 11.1 percent of its government budget on health, compared to the world average of 12 percent and the high-income average of 15 percent. While the rate is an improvement from just 9 percent in 2002, it doesn’t meet a target rate of 15 percent set in the 2001 Abuja Declaration.

But a solution is within reach.

“It appears, then, that many countries have scope to increase government health expenditure, which is vital to supporting progress towards [universal health care], and in particular to subsidizing the cost of services for poorer populations.”

The study is the first of its kind to track and assess international progress towards universal health coverage across the globe.

“As the saying goes ‘what gets measured, gets done,’ ” said Michael Myers, managing director at the Rockefeller Foundation. “With countries around the world taking steps to provide universal health coverage, the ability to identify gaps and effectively measure progress will add critical momentum to this global movement.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.