Sukarno, Suharto, Megawati: Why Do Some Indonesians Have Only One Name?

Indonesia, a dynamic and rising powerhouse in Southeast Asia that faces some difficult cultural and identity issues as it continues to advance economically, has at least one very unusual custom that confounds some foreigners -- the frequency of residents who have only one name.

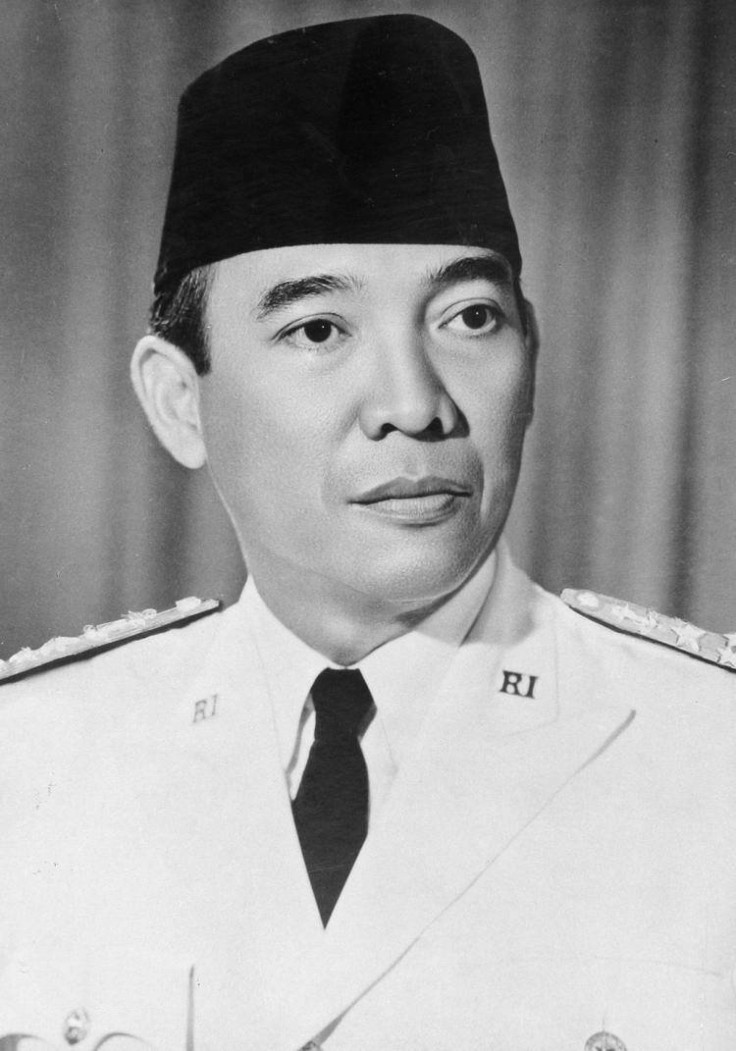

For example, the most dominant Indonesian political figure of the post-war period, a dictator who ruled the country for three decades, was simply named “Suharto.” Suharto should not be confused with the country’s first president, “Sukarno.” The current vice president of Indonesia is “Boediono,” although the president is a three-namer, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. Thus, the naming customs in Indonesia can be quite complex and confusing.

A reporter for the Christian Science Monitor, Dan Murphy, who spent many years in Indonesia, wrote that the occurrence of one-name Indonesians varies across the vast country. “People may have one name or two -- short names or long -- a given name followed by a family name or vice versa, or one name and one initial,” he said. “As a general rule, among ethnic Indonesians, the average citizen will have only one name while the middle class will tend to have two.”

Murphy added that typically, the higher a person's social standing, the longer his or her name. Long names, however, are often shortened for everyday use. A person with two names often uses one name plus the initial of the other name.

The Javanese, who represent about 40 percent of Indonesia’s population and account for the nation’s largest single ethnic group, tend to favor one name. For example, the Javanese leader Sukarno has a daughter named Megawati (who rose to become vice president) -- but she had a “suffix” surname, Sukarnoputri. So, in the Western sense, her whole name is Megawati Sukarnoputri -- but that translates as “Megawati, the daughter of Sukarno.” Strictly speaking, Sukarnoputri is not a ”surname” by Western standards.

An Indonesian blogger named Rasyad A. Parinduri estimated that fewer than 20 percent of his countrymen currently carry just one name, and the practice appears to be diminishing among the younger generation. Responding to Parinduri’s blog, a commenter named “Guntur’ said he believed there were more Indonesians with single names in the rural areas, less so in the metropolitan centers. “This may be partly because of the lack of education that people get in the rural areas, which automatically leads to naming one's child using a single name,” Guntur said. “Or for some religious and [ethnic] reasons, people tend to consider this single name ‘custom’ more appropriate in that their children may be better accepted in the social circles when they reached adulthood, if they go by single names.”

However, given Indonesia’s vast size and bewildering ethnic and cultural diversity, it is nearly impossible to make any declarations or generalizations about the country’s customs with respect to names. Ariel Heryanto, associate professor and deputy director at The Australian National University’s School of Culture, History and Language in Canberra, explained to International Business Times how complex the issue of names and surnames really is. “I know many Indonesians whose names consist of three or more words, none of which is a 'family name' shared by other members of the family,” he said. “So, having more than one name does not necessarily imply owing a family name.”

Heryanto also noted that there are many Indonesians who change names several times, or drop/add names, or slightly alter parts of their birth names. In some communities, including North Sumatra, North Sulawesi and the Maluku islands, there has been a long tradition of having a family surname. “Incidentally, these are areas where European missionaries were most successful in spreading Christianity,” he noted. “To what extent religion plays a part in constructing this tradition needs further investigation.”

Associate Professor Michele Ford, director of the Sydney Southeast Asia Centre at The University of Sydney in Australia, told IB Times that some ethnic groups in the country, like the matrilineal Minangkabau, actually have a clan name that derives from their mother's side. “This name is very important but has not traditionally been used as part of an individual name,” she said. “There is an interesting trend now of Minangkabau men establishing a 'surname' of sorts, either using their clan name of origin or giving their own name as a last name to their children.”

In addition, although Indonesia is overwhelmingly Islamic (accounting for an estimated 90 percent of the population), many Muslims in the country have not adopted Arabic appellations, which typically feature two or three names. “People don't think of themselves as Muslim or non-Muslim on the basis of the form their name takes,” Ford stated. “There are areas of Indonesia where it has long been common to take more Islamic-sounding names, whereas in Central and East Java, in particular, many very devout Muslims have very Javanese names.”

For example, former President Abdurrahman Wahid clearly has an Arabic name -- but “Wahid” is not his family’s surname. He was actually born “Abdurrahman Addakhil” -- and to confuse things even further, he was popularly known as “Gus Dur,” which derived from his Javanese origins.

The complexity and irregularity of names in Indonesia might play havoc with official documents and government forms. Indeed, Ford noted, it is quite common for Indonesians to have their names depicted differently in different kinds of records. It is possible to have just one name on a passport, but some people do other things, like use the Arabic 'bin/binti' titles for male/female -- especially overseas contract workers looking for employment in the Middle East. Heryanto indicated that there have always been widespread discrepancies and variations between the names found in official documents and the names used in daily life. “This discordance has been the norm, and not [the] exception,” he said.

But Heryanto assured that this scenario does not cause as much confusion as foreigners might expect. “Indonesians are [rather] used to the situation,” he stated. “Just like our traffic in major streets – where accidents are relatively rare -- may confuse outsiders.” Heryanto further pointed out that oral communication is more important in Indonesia than written language. “There is a very high level of nominal literacy -- more than 90 percent of the population can recognize characters and numbers -- but a low level of functional literacy,” he said. “So you have this paradox: Written texts (including sacred and legal documents) carry the extra weight of authority due to their distance from daily life, but which most people have neither the interest nor ability to comprehend. But they must live and interact with such things in accordance with those documents.”

For example, in Indonesia, when the traffic light turns red, it does not always mean "stop" to many drivers, he cited. Also, people often smoke right next to the sign which reads "no smoking," while others park their vehicle next to the sign that prohibits it.

Alas, as Indonesia integrates deeper into the global economy, it will be interesting to see if they normalize their confounding naming customs.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.