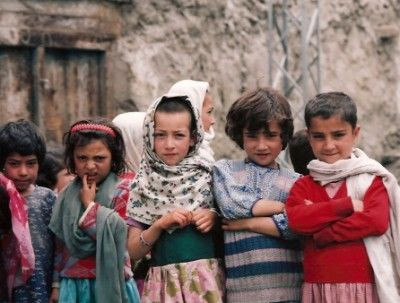

Swara: The Horrors Of Marrying Off Young Girls In Pakistan To Older Men To Settle Debts And Disputes

The subject of marrying off young girls in exchange for paying a debt in Pakistan resurfaced recently when a young child named Saneeda was taken by her estranged father for the purpose of giving her hand in marriage to another man she had never met before. The drama played out in Madyan, a hill station in the Swat district of Pakistan's mountainous Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (the same region where Malala Yousafzai hails from). The girl’s father, Ali Ahmed, needed to pay back a “debt of honor” -- after he had earlier eloped with a young woman from another valley, he feared a violent reprisal from that girl's family. To appease them, Ahmed promised to hand over his daughter Saneeda as well as a niece named Sapna as brides.

Agence France Presse (AFP) reported that young girls are often offered as brides as a form of “compensation” to settle disputes between families, tribes or whole villages. In Swat, where this custom is called "swara," an increasing number of young females are being used in this way as gifts, bribes and bargaining chips -- despite the removal of a brutal Taliban regime from the valley by the Pakistani army four years ago.

The arrangement for turning Saneeda into a bride was ordered by a jirga -- a village council of elders with enormous autonomous authority in remote areas. "We initially thought they can't take this girl away but then they [the jirga] increased pressure with every passing day to give her in swara," Saneeda's maternal uncle, Fazal Ahad, told AFP.

But Saneeda's family took the bold, courageous and highly unusual step of challenging the rule of the jirga. Saneeda eventually escaped this nightmare after a court provided her with protection, and police arrested her father and members of the jirga who imposed the swara. "There are many other cases of swara, but people in our area don't go to police and court and don't highlight such cases. We don't take matters of our women to the court -- the victimized girls have to bear it all," Ahad added. "People are slowly getting aware through media that this custom is an evil, so some of them have started reporting.”

Indeed, Saneeda, now seven years old, remains scarred by her ordeal -- she encounters daily insults and discrimination. "Whenever I go to school, children taunt me and tell me that I have been given in swara and will be married to a man," she said. Moreover, the other girl in this drama, Sapna, did not escape -- she married the man the jirga selected for her.

Official data indicate that nine incidents of forced child-brides were registered last year, up from only one in 2012. However, women's rights campaigners believe the actual number of such cases is much higher. An activist named Samar Minallah Khan has identified at least 132 cases of swara across Pakistan in 2012. Under Pakistani law, swara is illegal -- but since most victims (not to mention, perpetrators) are reluctant to air their dirty laundry in public, prosecutions are difficult.

The Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN) news agency, a project of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), reported that, under laws passed in 2004, people convicted of facilitating such marriages can be imprisoned for up to ten years. "In the cases of swara, people don't provide evidence against each other, because they are [usually] from the same village and community," Naveed Khan, a senior police official in Mingora district, Swat, told AFP. "In the single swara marriage case [registered] in 2012, all 12 accused [perpetrators] were set free because there was [a] lack of evidence against them. Nobody speaks up in such cases."

But last year, police arrested 65 people, including Saneeda's father, in connection with swara cases. Women's rights activists are seeking to press the government to more aggressively investigate and prosecute suspected cases of forced child marriages, while encouraging victims to speak up. "There are more than 15 cases of Swara, which have been highlighted," Tabassum Adnan Safi, a local rights campaigner, told AFP. "We are working to make women aware of the evilness of this custom. Besides these awareness campaigns, we also protest against Swara and raise voice for the protection.”

Minallah stated that the police and state courts need to challenge the entrenched jirgas who wield authority in rural Pakistan. "An awareness has been created against swara, that is why there are more reported cases, but the authorities need to take strict action against jirgas and stop them [from] violating the law," Minallah said.

However, some people in Pakistan defend swara as a necessary practice. "[Swara] is helpful in removing deadly enmities among scores of tribes, saves dozens of lives and brings peace among families," Syed Kareem Shalman, a Mingora lawyer, insisted to AFP. "If a family, which gets a bride in Swara mistreats her, faces revenge from the family who give their daughter to resolve the dispute."

In other parts of Pakistan, particularly in the southern Punjab, the practice of forcing a child into marriage is called "vani." The Express Tribune newspaper reported that police in the town of Mithanwali in the Muzaffargarh district of Punjab arrested 36 people -- including 20 men -- in connection with the attempted forced marriage of a 9-year-old girl who was declared "vani." The child became a helpless pawn in a deadly game of adultery and revenge -- a 30-year-old man was accused of having an illicit sexual relationship with a 26-year-old woman who was the daughter of a prominent tribal chief. In retaliation for besmirching the woman’s honor, her family demanded that her lover be killed and all of his property handed over to the woman’s father. However, the condemned man’s father begged for mercy and subsequently a local panchayat (council of elders similar to a Jirga) ordered that the young man’s 9-year-old niece be given to the aggrieved family as compensation. The child was indeed transferred over to the other family, along with 15 acres of property. When local police caught wind of these transactions, they freed the young girl, returned her to her family and arrested several adults who were involved.

Such cases of "swara" and "vani" dot the Pakistani landscape -- but it appears that, under pressure from the public, police are making more arrests to stop these illegal customs. "Yes, the laws have helped but ‘swara’, ‘vani’ and similar practices still go on," Minallah told IRIN, adding that the tougher new laws have prompted people to disguise the handing over of a young bride as something else to avoid prosecution. “The deal is not announced within the community as a ‘swara’ or ‘vani’ marriage, though within the families concerned it is known that the woman has been given away as ‘swara’ and is treated accordingly,” Minallah said.

She added that when a young girl is forcibly married off in this manner, her new "husband" is usually a much older man. Even worse, she is often mistreated and abused by her in-laws. "Practices like ‘swara’ continue… because it takes more than laws to change the way people behave,” Shaukat Salim, a lawyer and human rights activist based in Swat, told IRIN. “Much more awareness and the general empowerment of women are needed, if we are to see real change.”

But even if forced child marriages are barred by laws, many minors still become wives in Pakistan (presumably, not by explicit force). According to the Family Planning Association of Pakistan, about 30 percent of all marriages in the country involve child marriages. (Technically, under the law, no girl below 16 or boy under 18 can legally wed.) “I was married when I was 11,” a 20-year-old woman named Sadiqa Bibi told IRIN. “I lost my childhood forever, but times must change and I will not allow my three daughters to be married off before they are adults."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.