TEDx 'De-Extinction' Debate: Is Respawning The Wild A Good Idea?

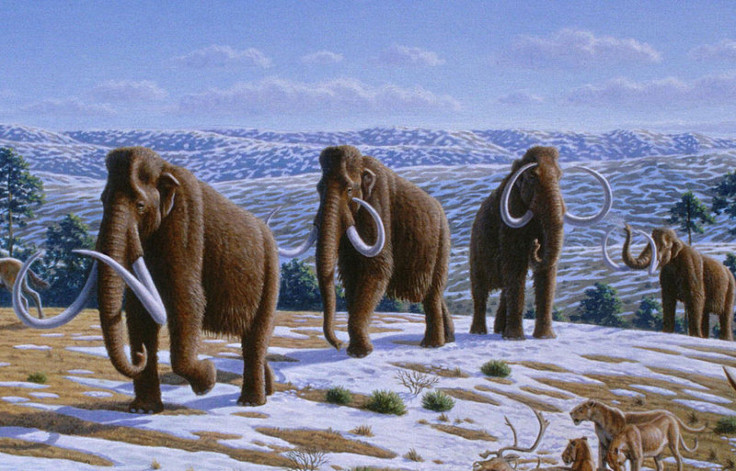

Scientists could potentially resurrect extinct animals such as the Xerces Blue butterfly, the Great Auk, the passenger pigeon and the woolly mammoth, but would that actually be a good idea?

The DNA of extinct species lives on in the fossils preserved in museums and under the earth and could be used to bring many lost species back into the world -- a “de-extinction,” if you will. (Some truly ancient species, like dinosaurs, are likely gone for good, though, since their DNA has probably degraded past comprehension.)

At a special TEDx event on Friday and in the pages and pixels of National Geographic, many experts sounded off on the risks, merits, drawbacks and feasability of “de-extinction.”

To clone, say, a woolly mammoth, there are a few different approaches to take. If scientists found a living sperm cell inside a frozen mammoth corpse, they could use it to fertilize an elephant egg and create a mammoth-elephant hybrid. Subsequent hybrids could then be bred to create something close to a pure mammoth, generations later.

A more likely resurrection method would be through cloning, either by taking the mammoth DNA sequence or a nucleus from a preserved mammoth cell, inserting it in an elephant egg cell and then kickstarting cell division with a chemical or electrical stimulus. The egg would then be put in a surrogate elephant mother, who would give birth to a relatively pure baby mammoth.

Proponents of “de-extinction” say that reviving lost animals could bring a lot of well-deserved attention to conservation, help scientists study what makes animals vulnerable in the first place and anchor efforts to “rewild” abandoned areas of land.

“Some extinct species were important ‘keystones’ in their region. Restoring them would help restore a great deal of ecological richness,” Steven Brand, the creator of "The Whole Earth Catalog," wrote in an opinion piece for National Geographic.

But detractors say the rise of the “de-extinction movement” could give people, especially lawmakers and business interests, a false sense of security. In his own piece for National Geographic, Duke University ecologist Stuart Pimm pointed out all the ways that the exuberance of “de-extinction” could actually make things worse for the environment.

"Why worry about endangered species?” Pimm wrote sarcastically. “We can simply keep their DNA and put them back in the wild later. ... Let's tolerate a high risk of extinction, because our white-lab-coated science rock stars can save the day!"

Plus, the world of the woolly mammoth and the passenger pigeon is very different than the world as it is today. To resurrect one animal, you may have to end up reviving the entire ancient food chain -- prey animals, ancient extinct plants, et cetera.

“If there's no habitat, no good chance for survival, then is it really moral?” science writer Brain Switek pointed out on Twitter.

While it might not be feasible to reintroduce woolly mammoths into a completely foreign (and warming) ecosystem, some animals that went extinct more recently might be able to weather the present climate. The last wild thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, was shot in 1930. It might not be too late to bring it back.

But shrinking habitats and climate change are already threatening modern-day species across the planet. What if we resurrected animals from the past only to see them go extinct again?

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.