Toxic Radon Levels Are Rising In Pennsylvania As Natural Gas Fracking Booms

Pennsylvanians worried about the effects of natural gas drilling may have another reason for concern. Homes closest to fracking zones have been exposed to rising levels of cancer-causing radon ever since the state’s drilling boom began in 2004, a new public health study found. The analysis is part of a growing body of research that explores how widespread shale gas production affects the air, water and human health -- and what, if anything, should be done to limit the impacts.

Radon is a naturally occurring radioactive gas found in rocks and soil. While the gas seeps through cracks in home foundations and local water wells on its own, the disruptive process of fracking frees up even more radon and other potentially harmful materials and brings them to the surface. After smoking, radon is the second-leading cause of lung cancer in the United States.

Researchers found that radon levels in active gas-drilling counties have risen significantly over the past decade, with 42 percent of the buildings analyzed showing radon levels above what U.S. environmental officials consider safe, says the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which published the study Thursday in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives.

Homes and buildings in rural areas, where most of the gas wells are located, had a 39 percent higher concentration of radon than urban dwellings. Buildings with well water had a 21 percent higher radon concentration compared to buildings hooked to municipal water supplies, researchers said.

The results don’t offer direct proof that fracking is to blame for the boost in radon, but the fact that radon is rising where fracking is most prevalent points to the need for additional research, said Brian Schwartz, the study’s leader and a professor of environmental health sciences at Johns Hopkins.

“I’m not prepared to say yet that this industry is causing radon levels to go up in people’s homes,” he said. “But it’s one piece of information that should make us somewhat concerned.”

Schwartz said the idea for the study, which was conducted with Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System, grew out of a concern that higher radon levels could lead to more cases of lung cancer among Pennsylvanians. “That’s what motivated us to take a look, to try to protect public health,” he said. “We didn’t expect to find what we did.”

860,000 Measurements

For the study, researchers analyzed more than 860,000 indoor radon measurements gathered by the Pennsylvania Department of Environment Protection (DEP) from 1989 to 2013. They also factored in information about the season, weather, temperature and other environmental influences that might have influenced radon levels.

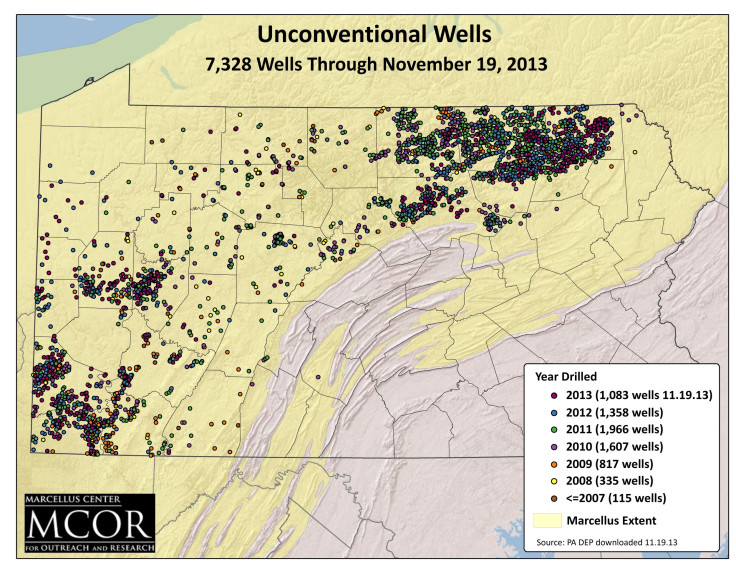

Next, they combined the radon figures with data about fracking wells, including geographic coordinates, the date when drilling began, the depth of the wells, the point at which shale rock was split apart to release natural gas and the amount of gas produced during particular periods. Between 2005 and 2013, nearly 7,500 unconventional natural gas wells were drilled in Pennsylvania using the hydraulic fracturing process. Up until this period, most gas wells were drilled using conventional methods, which generally are done at shallower depths and don’t involve cracking apart shale rock.

By boring thousands of holes in the ground, “the fracking industry may have changed the geology and created new pathways for radon to rise to the surface,” said Joan Casey, who authored the study as a doctoral student at Johns Hopkins and earned her Ph.D. last year. “Now there are a lot of potential ways that fracking may be distributing and spreading radon.”

Schwartz said the findings do have caveats. The DEP data the researchers used do not include information about whether families use gas or electric stoves in their homes, if homeowners recently repaired their foundations or if houses in particular areas are older -- all of which are variables that may or may not influence radon readings in buildings. Including that data “could either strengthen or weaken our associations,” he said. Researchers also found rising radon levels in parts of Pennsylvania without fracking.

Thursday’s report follows an earlier radon study by the DEP, which found that radon levels are not high enough to elicit concern at certain natural gas sites.

But Susan Rickens, a spokeswoman for the agency, said the studies aren’t contradictory because they’re not comparable. In the DEP report, an environmental monitoring firm studied outdoor air samples near natural gas wells, waste transportation sites, waste disposal sites and compressor stations. Researchers didn’t look at radon levels inside buildings. The study found that measurements in both the air and extracted natural gas did not surpass normal levels.

“There is little potential for additional radon exposure to the public due to the use of natural gas extracted from geologic formations located in Pennsylvania,” the DEP wrote in January.

Rickens said the DEP would review the results of the Johns Hopkins report and see if it warrants further study by state environmental officials. “We are in complete agreement about the health risks that radon poses to Pennsylvania,” she said. “This is an issue that needs to be of concern to all Pennsylvanians, regardless of where they live.”

Energy In Depth, a program of the Independent Petroleum Association of America, disputed the Johns Hopkins study, arguing that the data do not support the researchers' conclusions.

Broader Conflict

Still, the differing conclusions -- that fracking is, or is not, potentially boosting radon levels -- points to the broader conflict playing out in a state polarized by shale gas production. The industry employs tens of thousands of people and generates hundreds of millions of dollars in state revenues each year, but opposition groups warn the boom comes at a steep cost to residents and the environment. All the while, scientific attempts to qualify fracking’s health effects are sending mixed messages.

Last fall, it was learned that three widely cited DEP studies of air emissions at shale gas sites in Pennsylvania omitted important data, raising questions about the state’s conclusions that air pollution from drilling, fracking wastewater and compressor stations don’t pose a public health risk. The studies omitted measurements of key air toxics and calculated the health risks of just two of more than two-dozen pollutants, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported in October.

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf, who took office in January, had pledged to tackle some of the public’s concerns and toughen state regulation of the fracking industry. The Democrat recently restored a moratorium that blocks new shale drilling in state parks and forests. In March, Wolf proposed stricter standards for how natural gas companies store waste, dampen noise and affect public water resources. The moves are facing stiff resistance from the drilling industry, which claims the tighter regulations will make it harder to do business.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.