UK Election 2015:The UKIP Paradox, With Millions Of Votes And Only One Seat

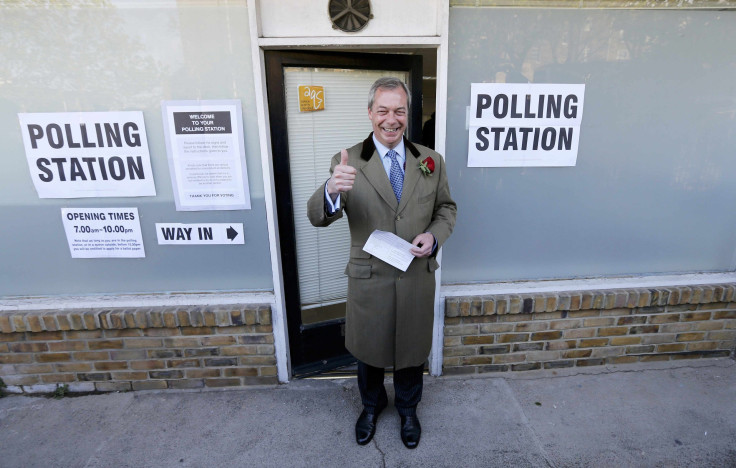

The UK Independence Party, the anti-immigration right-wing party that was considered a possible breakaway success in Thursday's British election, is headed instead for defeat, with only one seat in parliament. Its leader Nigel Farage may be out of parliament himself.

For a party that was tipped as the rising force in English politics, Thursday's result looks like a stunning debacle -- and will, if confirmed, keep UKIP on the political fringe. The Conservatives who look headed for victory, according to exit polls, may not need its seats to govern; they are projected to win 316 seats, which added to the 10 projected for their current coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats, is enough for a thin majority -- just three above the 323-seat threshold.

But the paltry number of seats won by the party does not paint the full picture. UKIP has in fact done exceptionally well in percentage terms, and only the quirks of the British electoral system with its first-past-the-post system are keeping it out of the circle of power. At midnight New York time, with 276 seats already assigned, it had won more than 1.3 million votes or 11 percent of the electorate, making it the third biggest party in the United Kingdom.

The popularity of Farage's message, based on a return to values described as traditionally British and a deep antipathy for the European Union, is easy to gauge by the growth in the UKIP vote, which showed an increase of 8.6 percent from the previous election. No other party has seen such an increase. By contrast, all three mainstream parties have seen their share of the vote fall -- only slightly for the Conservatives and Labour, and a disastrous fall for the Liberal Democrats, who slipped by 14 percent.

A senior advisor to Farage has said that UKIP might only get one seat - Clacton. #ge2015

- Chris Mason (@ChrisMasonBBC) May 8, 2015Farage himself looks headed for humiliation; he said he would quit if he failed to win a seat in South Thanet, in the southern English county of Kent. Now it looks like that is precisely what will happen, with the leader coming in third. (But according to a UKIP top donor quoted by a Times journalist, he might stay -- he has after all won over millions of Britons to his message, and may save face by handing in a resignation that the party would reject.)

Labour sources tell me Farage could come third in South Thanet based on the boxes opened so far, with the Tories "comfortably in the lead".

- Tom Pugh (@Tom_PughPA) May 7, 2015The party's 2014 manifesto for the election to the European Parliament -- when it recorded a triumph, ending up as the largest party in Britain -- promised that its members would vote "against the EU’s encroachment on our democracy" and work to get the U.K. out of the European Union, on the premise that its economy would do better if freed from the EU.

Yet, the irony for the UKIP is that under the most European of electoral systems, proportional representation, it would have made a historical sweep of seats on Thursday -- while under the typically British system of first-past-the-post, it is a consensus giant but a parliamentary midget. The election for the European Parliament last year was held with the proportional system; accordingly, the UKIP got the most seats, because it got the most votes.

The bizarre situation Farage faces was summed up well by the BBC's former political editor, Andrew Marr, who noted early Friday that electoral system reform has always been a left-wing cause in Britain -- but that the rising disconnect between the UKIP's popularity and its numbers in parliament might push it to make the introduction of proportional voting an eminently rightist issue.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.