UN Climate Change Initiative Lets Users 'Offset' CO2 Emissions By Investing In Clean Energy

The United Nations is making it easier for companies and people to "offset" their carbon dioxide emissions by investing in clean energy projects in developing countries. The initiative aims to minimize carbon pollution in the short-term as countries wrestle with shifting their energy mix from fossil fuels toward lower-carbon alternatives.

"We would like to puncture the myth that 'carbon neutrality' is impossible," Christiana Figueres, the U.N.'s climate change chief, said in a Tuesday meeting at U.N. headquarters in New York City.

The platform, called Climate Neutral Now, lets visitors calculate their personal carbon footprints. The average U.S. citizen generates nearly 20 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in a given year, although a city-dwelling vegetarian who recycles and doesn't drive a car only netted about 5 tons of carbon dioxide, according to the tool. The platform is far from comprehensive, however. It doesn't ask visitors to tally total airline miles traveled -- a major emissions source -- or calculate emissions from purchases of consumer goods, including clothing, electronics or home decorations, all of which carry a carbon burden.

Visitors can use their carbon counts to figure out how many "certified emissions reductions," or credits, they should purchase. For $3.50, a user can back a small-scale hydroelectric plant in Kerala, India, and offset 1 metric ton of carbon. A $2.40 credit backs a methane-capture facility at a swine waste treatment plant in Chile. Other options include biomass solar and wind power projects, energy efficiency initiatives and reforestation programs in dozens of countries.

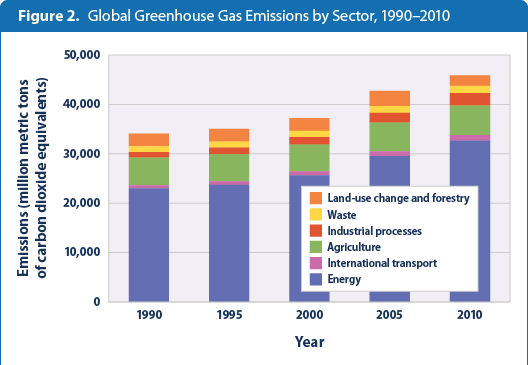

Climate scientists say the world's total greenhouse gas emissions must peak within 10 years and then swiftly decline in order to keep temperatures from rising above 2 degrees Celsius (3.2 degrees Fahrenheit), the level needed to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change, including brutal drought and widespread flooding. By 2050, the planet must become carbon neutral, meaning any remaining emissions will be absorbed by trees and wetlands, or captured and stored underground.

Figueres is spearheading the ongoing negotiations for a global climate treaty. Nearly 200 nations have agreed to forge a plan to reduce worldwide emissions during a U.N. conference in Paris this December.

Carbon offset programs first emerged after the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the treaty under which the European Union and other industrialized countries -- excluding the United States and China -- agreed to slash emissions. The U.N. launched the Clean Development Mechanism to help launch environmental projects in developing countries by drawing dollars from wealthier nations and large companies.

A decade later, the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change confirmed it found "unequivocal" evidence of global warming and that human activities were mostly to blame. The findings energized the climate movement and sparked renewed interest in climate offsets. For travelers and businesses concerned about their carbon footprints, buying credits was more realistic than staying at home to avoid airplane emissions, but still enabled them to support clean energy growth.

The enthusiasm didn't last long, however. As international climate talks sputtered in Copenhagen in 2009, and with the global financial crisis rippling through the world's economies, suddenly carbon credits seemed like a frivolous extra to many consumers. With demand dipping, the world's carbon offset market is largely oversupplied, which is pushing down prices.

After peaking in 2008 at $7.3 per metric ton, the average global price for voluntary credits has dropped to $3.8 per ton of carbon dioxide, according to Ecosystem Marketplace, which tracks the industry.

Still, the market is far from dissolved. Companies, governments and individuals voluntarily spent nearly $4.5 billion over the past decade to purchase nearly 1 billion offsets from projects that halt deforestation, develop renewable energy projects, boost energy efficiency in buildings and provide cleaner-burning cookstoves to low-income communities, Ecosystem Marketplace found in a June report.

Critics of carbon offsetting have said they worry the programs take the pressure off energy companies, power utilities and airlines to invest in energy efficiency or lower-carbon energy sources. They argue there's little proof that initiatives actually cancel out emissions created by driving a car, burning coal-fired power or watching hours of television. In the worst cases, some carbon credits have been sold multiple times, or green initiatives backed by credits fail.

Lambert Schneider, who chairs the executive board for the Clean Development Mechanism, said the U.N.-backed program avoids these pitfalls through rigorous reviews, accounting and audits. "No other mechanism has such a comprehensive international oversight in place, with so many checks and balances," he said on the sidelines of the Tuesday meetings.

U.N. officials also said they set a goal to make all U.N. agencies and organizations carbon neutral by 2020. Figueres suggested the deadline should be sooner. "I don't think it's acceptable for anymore [to wait], because we've actually made it so much easier," she said. "We have to up the ante."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.