UnitedHealth Group (NYSE:UNH) Q1 Forecast: Healthy Earnings Expected As Questions Remain About Insurer's Obamacare Complaints

UnitedHealth Group (NYSE:UNH) plans to release its first-quarter earnings Tuesday, as the company expresses growing concern over the profitability of health plans sold on exchanges created under the Affordable Care Act. As the report comes, a single question looms above others: If Obamacare policies prove as financially detrimental as UnitedHealth says, what will the company do?

United, the U.S.'s largest private health insurer, first threatened in November to pull out of Obamacare marketplaces in 2017. The company later said it had lost $720 million in 2015 because of those exchanges, and has since said it will exit exchanges in Michigan, Arkansas and Georgia next year.

Yet United's earnings for the first quarter of 2016 are projected by analysts to be robust, at $1.72 earnings per share, up from $1.26 the previous quarter and $1.46 the first quarter of 2015.

“That’s a pretty significant increase in earnings for them,” Jeffrey Loo, an equity analyst at S&P Global, said of the forecast for United's first quarter of 2016.

In its 2015 results, United said it raked in $157.1 billion in revenue, a 20 percent increase from the prior year. It has also estimated its 2016 revenue would exceed $180 million, with adjusted earnings per share ranging from $7.60 to $7.80 for the year.

Several factors may play a role in the inconsistencies between United's claims of losses it attributes to sicker and therefore expensive patients enrolling in Obamacare, and its healthy earnings. In 2015, the company said earnings from operations had declined $238 million from the previous year, to $6.8 billion, and operating margins had fallen to 5.1 percent, due to Obamacare exchanges. If it excluded losses from those marketplaces, however, its 2015 earnings from operations amounted to $7.6 billion, an increase of 8 percent from the year before.

One factor is that United's ACA customers are only a fraction of all those enrolled in its plans, estimated to be 800,000 by the end of the most recent open enrollment period, which ended Jan. 31. By contrast, United's enrollment has grown by 40 percent since 2010 to reach nearly 13.5 million people in 2015.

“What they don’t talk about is the benefit they received from the Medicaid expansion,” Loo said, referring to one of the pillars of the Affordable Care Act, which granted states federal dollars to extend the low-income insurance program to a broader swathe of their populations. “Although the margins are smaller for Medicaid patients, they are still benefiting from leverage and they’re still making a profit on these Medicaid patients.”

In its 2015 report, United said it added 250,000 patients to its Medicaid programs from the previous year, for a total of more than 5.3 million such customers.

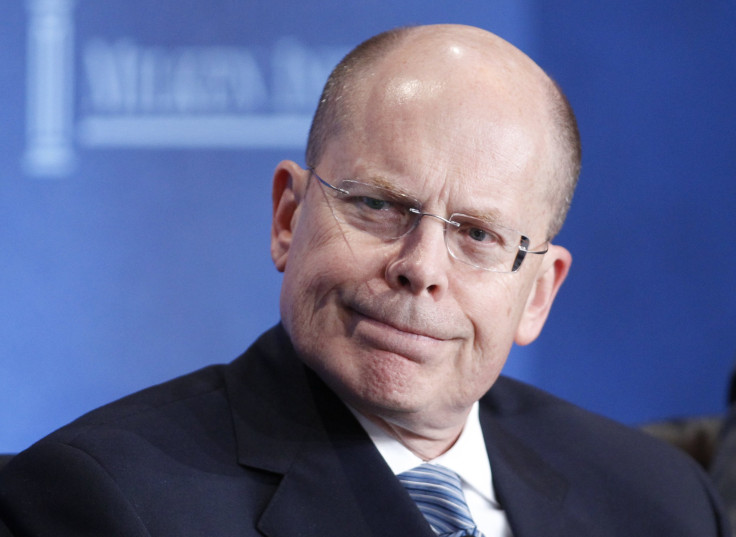

United has been vocal about its Obamacare losses. “We can't really subsidize a marketplace that doesn't appear at the moment to be sustaining itself,” CEO Stephen Hemsley said in a call with analysts in November.

Executives at other major health insurers also are questioning the viability of remaining in the exchanges.

“This business remained unprofitable in 2015, and we continue to have serious concerns about the sustainability of the public exchanges,” said Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini in February, after announcing losses of $140 million in 2015 that he attributed to the exchanges. Aetna also said, however, that it expected to break even in 2016.

Given the fact that Obamacare exchanges are in their third year, some have suggested it would be too soon for insurers to give up on them, especially given the additional 20 million people that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services says have gained health insurance as a result of the law.

United has less experience in exchanges than some other insurers, having entered only four states' marketplaces during the first year of the exchanges, 2014, before expanding to 23 states in 2015 and 34 in 2016.

“The Affordable Care Act has been a net benefit for health insurers,” said Loo. “Obviously they took on a lot of sick patients as well, but they get a lot of leverage by increasing membership.”

Others point to the financial consequences that United's decision to pull out of exchanges could have for patients.

The Kaiser Family Foundation released an analysis Monday examining the impact of a UnitedHealth Group withdrawal. It concluded that in 29 percent of the 1,855 U.S. counties where United offers plans, or for 1.1 million people, the number of insurers would drop from two to one, essentially putting an end to any competition that could keep prices lower. In another 29 percent of counties, 1.8 million people would have just two insurers to pick from. Having three insurers to choose from is generally considered sufficiently competitive.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.