What Is The Ichthyosaur? 'Storr Lochs Monster' From Middle Jurassic Era Unveiled In Scotland

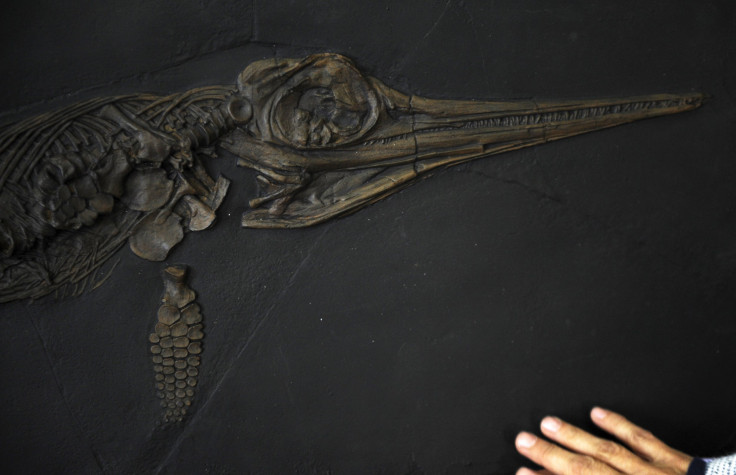

After spending decades out of the public eye, the skeleton of a 13-foot ichthyosaur — dubbed the Storr Lochs Monster — has emerged thanks to Scottish scientists, reported National Geographic Monday. The skeleton of the extinct marine reptile was first discovered some 50 years ago on Scotland's Isle of Skye but was tucked away in museum storage.

The ichthyosaur lived about 170 million years ago, co-existing with dinosaurs. They are thought to have been the kings of the ocean at the time, existing at the top of the food chain before dying off apparently because of climate change and slow evolution.

"The creatures were the dolphins of their time: fast swimmers with long, narrow snouts and cone-shaped teeth perfect for eating squid and fish," wrote National Geographic.

The Storr Lochs Monster, a 13-foot-long ichthyosaur from 170 million years ago via @NatGeo

— The Tylt (@TheTylt) September 6, 2016

https://t.co/0YSHXRguYX pic.twitter.com/rgTx0vgsE5

The fossil, which was preserved nearly intact, is considered a scientific prize because of the era in which it lived, the Middle Jurassic.

"The Middle Jurassic is one of the most poorly known times in the history of dinosaurs and in the history of other reptiles like ichthyosaurs," said University of Edinburgh's Steve Brusatte, a member of the team examining the fossil, according to USA Today.

The skeleton was kept in storage because it was encased in extremely hard rock. A group of experts from University of Edinburgh, National Museums Scotland and energy company SSE allowed paleontologists to get the skeleton out of the rocky encasement. It was debuted to the public this week.

"Although some people think that sea monsters live here today in our lakes, there were actually real ones that lived here over a hundred million years ago," Brusatte said, according to National Geographic.

The fossil was found in 1966 by an amateur collector named Norrie Giles, who ran the local hydropower plant and spotted the find while on a walk. His son, Allan Gillies, an engineer at SSE, pushed for the fossil's extraction from the stone after his father's 2011 death.

"Dad’s not around to see it himself, but I know he’d be very, very pleased to know that it’s finally being displayed, and he’d also be very pleased to know that it’s the company he worked for that helped to make it happen," Allan Gillies said, via National Geographic. "It’s sort of completing the story."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.