What Is Shadow Banking? Risky Sector At Center Of Sanders-Clinton Debates

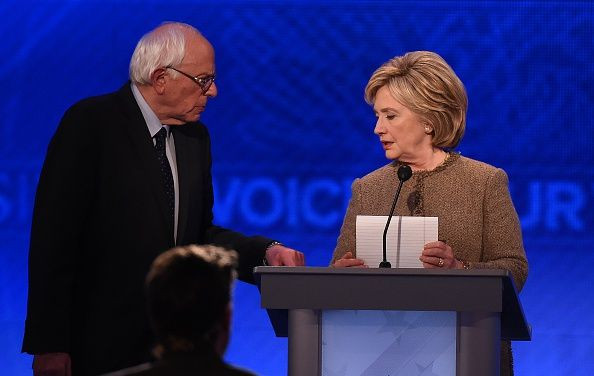

A new bogeyman crept into the contest for Democratic presidential nominee this week: shadow banking. In advance of Bernie Sanders’ speech on Wall Street reform Tuesday, rival Hillary Clinton's campaign jabbed the Vermont senator over accusations that his financial reform policies let shadow banking institutions off the hook.

“Senator Sanders should go beyond his existing plans for reforming Wall Street and endorse Hillary Clinton’s tough, comprehensive proposals to rein in risky behavior within the shadow banking sector,” said Gary Gensler, Clinton’s campaign finance chief and a former regulator with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

The comments, which prompted a sharp retort from the Sanders camp, illuminate the two presidential hopefuls' divergent approaches to regulating Wall Street. While Sanders has focused his policies on a vow to break up the six largest U.S. financial institutions, Clinton’s plan devotes significant attention to Wall Street’s periphery, known as shadow banking.

Beyond revealing the candidates’ philosophical divides, the debate raises the question of whether shadow banking activities have been sufficiently policed since the financial crisis of 2007-2008 — a calamity largely fueled by shadow banking excesses.

What Is Shadow Banking?

Shadow banking is a catchall title for all the financial services that occur outside of federally insured banks. Despite the ominous-sounding epithet, these institutions perform services central to the everyday operation of the U.S. economy.

Online mortgage lenders, hedge funds, private equity firms, money market funds, insurance companies, payday lenders, investment banks: At times, all of these fall under the broad definition of shadow banking.

The sector has grown astronomically in the past few decades, particularly in the years before the financial crisis. And free from lending rules and other restrictions placed on commercial banks, institutions in the shadow banking sector played a central role in the meltdown.

As explained in entertaining style in the box-office hit "The Big Short," nonbank lenders created risky subprime loans. Special vehicles set up by banks and hedge funds bundled those iffy loans into high-rated securities. Insurance companies like AIG sold collateralized debt obligations built off of those securities.

The crisis reached a boiling point when the housing market’s collapse revealed how deeply some banks were invested in subprime securities. The network of shadow lenders that keeps banks stocked with short-term loans — called repurchase agreements, or repos — buckled under the pressure.

“When those institutions got word that the banks were on shaky ground, they refused to give banks the financing they relied on,” said David Zaring, a professor of legal studies at the Wharton School.

Yet even after the crisis, the shadow sector remains an inextricable part of the financial markets. Though the repo market has diminished, big banks continue to rely in part on short-term financing, which accounts for fully half of the liabilities between broker-dealers. In 2015, nonbank institutions like Quicken Loans originated more mortgages than insured banks.

Regulators have shared their concerns that the lessons of the crisis haven’t been applied -- a concern that Clinton has latched onto: “Serious risks are emerging from institutions in the so-called shadow banking system, including hedge funds, high-frequency traders, nonbank finance companies,” Clinton said last summer.

How Is Shadow Banking Regulated?

Companies involved in shadow banking are subject to relevant lending laws. Mortgage originators, for instance, must follow home lending rules whether they are federally insured banks like Wells Fargo or online lenders like loanDepot.com.

But most shadow banks are free from the regulations that ensure big banks have enough spare capital to weather a financial shock. And the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, which placed (some think) onerous new restrictions on the derivatives market and on the largest banks, avoided overhauling the shadow sector.

“One of the things that Dodd-Frank did was leave large sectors of shadow banking alone,” said Zaring. “It focused instead that banks were safe and sound, or at least safer and sounder.”

Dodd-Frank’s landmark financial reforms did affect sections of the shadow market. For example, companies that sell exotic financial products like mortgage-backed securities now have to share partly in the risk of those products, diminishing the chance that toxic products will proliferate.

And the bill empowered the government to draw up a list of systemically important financial institutions for additional oversight. Shadow institutions, including AIG and General Electric Capital, joined megabanks like JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America on the list.

But the shadow sector remains deeply entwined with the financial system. In a November speech, Federal Reserve Governor Daniel Tarullo worried that despite regulatory advances, oversight of shadow banking could fall short: “Risks to financial stability may arise anew from activities mostly or completely outside the ambit of prudentially regulated firms,” Tarullo said.

What Are Clinton and Sanders Proposing?

Increased regulations on shadow banking activities make up a central plank of Clinton’s financial reform plan, a focus that has so far been lacking in Sanders’ public comments — and a fact Clinton’s campaign has not been hesitant to publicize, deeming Sanders’ approach “hands-off.”

The Sanders campaign responded that their candidate "won’t be taking advice" on financial reform from Gensler, who before becoming a tough post-crisis regulator was a Goldman Sachs alum and Treasury Department official who midwifed a Bill Clinton-era bill that kept derivatives out of the purview of regulators. (Sanders attempted to block Gensler’s 2009 appointment to the CFTC for that reason.)

Clinton’s plan would force repo market financiers to hold more collateral, require hedge funds and private equity firms to strengthen their disclosures and generally expand the ability of regulators to police the shadow banking sector.

Sanders’ plan to break up the largest financial institutions within his first year in office would also affect shadow banking institutions, some of which would likely be designated “too big to fail.”

But Zaring cautioned that although breaking up the biggest banks would inherently reduce systemic risks, it would guarantee financial stability.

“If you have a bunch of small financial institutions that are all doing the same thing, they could all fail at once,” Zaring said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.