Who Is David King? Lead Plaintiff In King v. Burwell Supreme Court Case Challenging Affordable Care Act

David King, the lead plaintiff in the Supreme Court case King v. Burwell, didn't want to buy health insurance. The 64-year-old Vietnam veteran, a resident of Fredericksburg, Virginia, works as a limo driver and makes $39,000 a year, according to a post on the Supreme Court blog, and if it weren't for subsidies afforded him by the Affordable Care Act, King wouldn't be able to -- or have to -- buy health insurance.

Based on his income, King could pay $275 a month for health insurance that actually costs $648 a month, according to the Supreme Court blog. Federal subsidies outlined in the Affordable Care Act of 2010 would cover the difference in cost. But if subsidies didn't exist, King would be exempt from the individual mandate, the Affordable Care Act's requirement that everyone have health insurance or pay a penalty, because the cost of insurance would have been unaffordable for King. Depending on whom you ask, it was the subsidy that either allowed or forced him to buy health care coverage.

As a result, King and three other Virginia residents -- Douglas Hurst, Brenda Levy and Rose Luck -- filed a lawsuit against the government arguing that subsidies were supposed to be only for those purchasing health care through state-run health exchanges -- not the federal one. Their case focuses on four words: "established by the State.” Thirty-four states, including Virginia, opted against establishing their own exchanges under the Affordable Care Act, instead allowing residents to purchase health care through HealthCare.gov, the federal marketplace. Those four words, the plaintiffs' suit argued, meant subsidies were only for people purchasing health care on exchanges "established by the State." Lower courts ruled against them, but in July 2014 King and the others petitioned the Supreme Court, and in November the justices said they would hear the case.

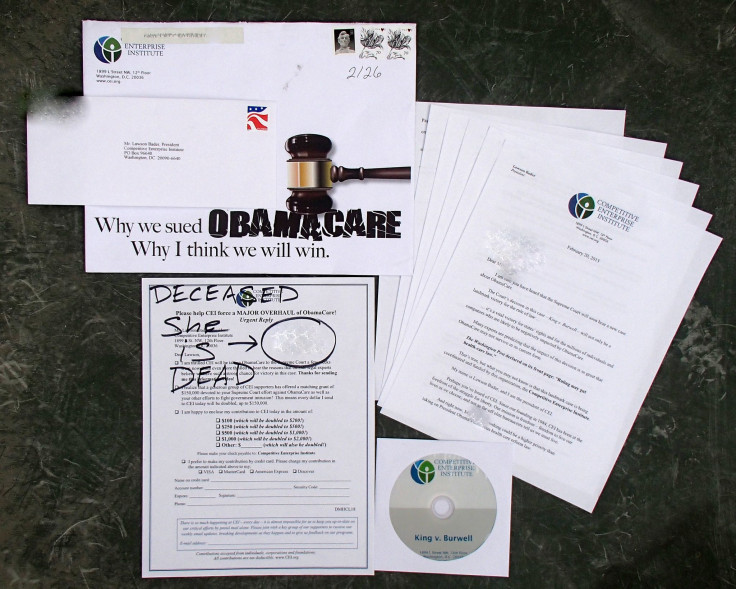

The idea and arguments behind the case actually date back much further than King's personal situation. The New York Times, Mother Jones and other media outlets have reported how the case's main argument was in the making as early as 2010, when a lawyer from Greenville, South Carolina, shared a tiny detail regarding tax credits in the Affordable Care Act at a conference run by the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. Gradually, that information was developed into an idea to challenge the health care law, thanks to Jonathan Adler and Michael Cannon, a law professor and a director at the Cato Institute, respectively. "We were the first ones to lay it all out," Adler told the New York Times. Another group, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, then sought and found plaintiffs for the lawsuits. In September 2013, King and the three others were the plaintiffs in a case, King v. Sebelius, filed in a district court in Virginia. That court ruled against against the plaintiffs in the case that is now King v. Burwell.

In early February, news reports circulated that as a U.S. Army veteran who served in Vietnam, King would qualify for health care coverage through the Veterans Affairs, creating doubt that he could rightly challenge the law in the Supreme Court case. But those reports do not appear to have affected King's standing, and the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in King v. Burwell at 10 a.m. Wednesday. A ruling is expected to be issued by June.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.