Why China Just Made A $20B Investment In Venezuela

Venezuela is suffering from plummeting oil prices, runaway inflation and shortages of basic foodstuffs, but it now has at least one lifeline: a $20 billion investment package from China, announced by Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro this week. But with Venezuela facing a recession, inflation over 60 percent and widespread predictions of a default on its debt this year, some analysts say it’s hard to pinpoint China’s incentive for handing over the funds.

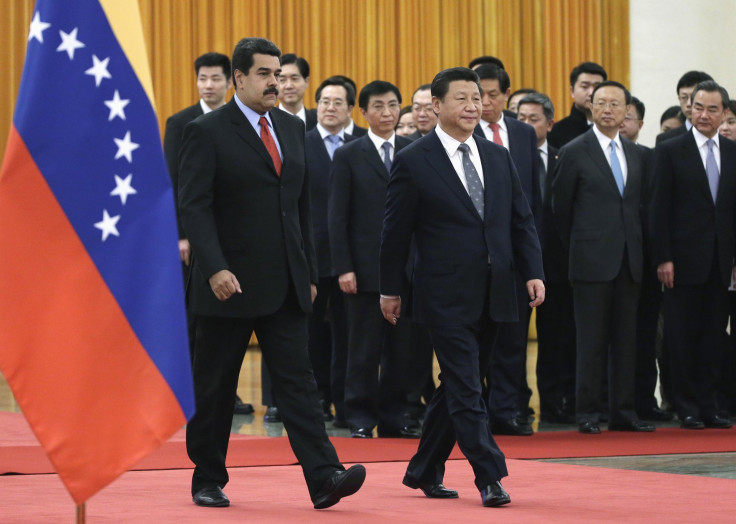

Venezuela has been particularly hard hit by declining oil prices, which fell by 50 percent in the second half of 2014 and have dipped below $50 a barrel. The hit to Venezuela’s primary export has taken its toll on the country’s foreign reserves, and Bloomberg estimates Venezuela’s risk of default this year at 90 percent. President Nicolas Maduro, who has vehemently denied that the country would default on its debt, traveled to China this week to negotiate more economic cooperation, a visit that many observers interpreted as a last-ditch effort to secure emergency assistance from Beijing.

Following a meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping Wednesday, Maduro announced that China, through the Chinese Development Bank and Bank of China, agreed to invest $20 billion in energy, social and industrial projects over the next decade, although he didn’t specify any of the projects involved. Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Hong Lei said in a press conference that China would support “efforts by the Venezuelan side to adjust its economic structure and build a production-oriented economic model,” but he didn’t confirm the investment amount or offer additional details on how the money might be used. It also remains unclear whether any part of the recent agreement involves loans that Venezuela could use to make additional debt payments.

China has granted Venezuela more than $50 billion in loans since 2007, around $20 billion of which is still outstanding, and Beijing remains Caracas’ largest creditor. About half of the nearly 600,000 barrels of oil Venezuela ships to China every day goes toward servicing that debt.

Margaret Myers, director of the China and Latin America program at the Inter-American Dialogue, said she was surprised by the move, noting that some of China’s oil companies and major banks have been increasingly cautious about undertaking risks in recent months. “There are a lot of voices in China that are opposed to continued engagement with Venezuela,” including from within the government, she said. “They’re very worried about what is happening with political risk in Venezuela, what Maduro’s plans are, and social stability.”

The decision to invest in Venezuela “doesn’t jibe,” she added.

Miguel Tinker-Salas, a professor of Latin America Studies at Pomona College, noted that Maduro’s announcement came just as China declared a commitment to invest $250 billion in Latin America ahead of its meeting with the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, which is currently underway. The investment deal, he said, was simply part of China’s wider strategy to gain a stronger foothold in the region.

“It’s part of a broader relationship in the context of a multipolar world where Latin America can seek better terms of trade, as opposed to dealing with one traditional ally, the U.S.,” he said.

Tinker-Salas also dismissed the default fears circulating around Venezuela. “One thing Maduro and [former Venezuelan President Hugo] Chavez have both done is consistently paid off their international debt,” he said. “There are economic difficulties and challenges, but when Chavez came to power in 1999, oil was $7 a barrel. The larger issue is whether Venezuela can limit its dependence on oil.” The extent to which the new investments could assist with that goal is still unknown, he added.

Observers have usually viewed China’s increasing investments in Latin America as a way for Beijing to access more resource markets and build up geopolitical influence in the region. But Patrick Chovanec, a China analyst and chief strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management, said the calculation was different with Venezuela. “The reality is that China bought into Venezuela at a very high price, and now that price has dropped significantly,” he said.

Chovanec said he suspected the deal could represent a debt restructuring agreement in disguise, given the Chinese Development Bank’s “massive exposure” in making previous loans to Caracas. “It would be painful for the Chinese Development Bank to say, ‘You’re right, we lost a lot of money.’ It’s much easier, if you have an opaque banking system, to extend and pretend and say, ‘Everything’s fine.’ And since nobody can actually calculate the present value of the loans, who’s to say you got a bad deal?”

“Even if China thought it was getting some geopolitical benefit – and I think it’s sort of hazy what sort of benefit it would get – $20 billion is a pretty steep price to pay for a country that everyone thinks is going to default,” he added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.