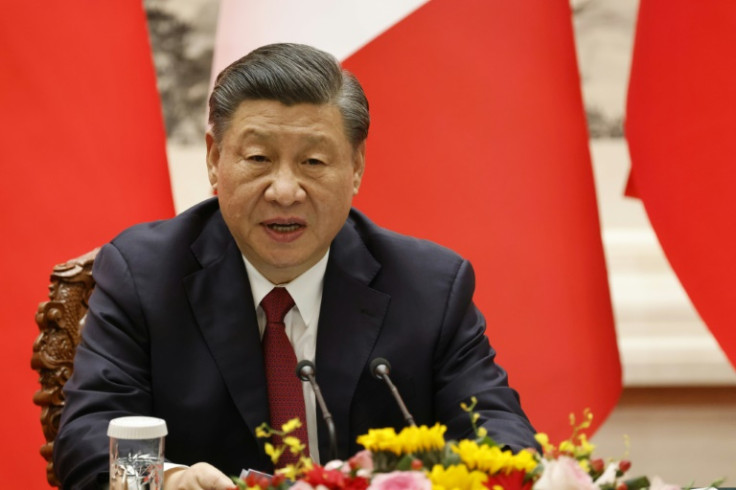

Xi Jinping Should Solve China's Problems Before Solving Africa's

China's President Xi Jinping should spend more time at home solving the country's growing economic problems and less time trying to solve the problems of other countries.

This week, Xi is in Africa, where he joined other leaders of BRICS, the five largest emerging market economies, to discuss geopolitical issues.

But the real reason for his trip may differ: to strengthen ties with African countries. On Tuesday, the Chinese leader skipped a business forum of the BRICS economic group where he was to deliver a speech on the Chinese economy.

Instead, he met with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa to discuss ways to deepen cooperation between China and South Africa, as relations between the two countries enter a "golden era."

China is Africa's biggest trading partner, with Sino-African annual trade exceeding $200 billion per year. More than 10,000 Chinese corporations are currently operating throughout Africa, building the continent's infrastructure.

With more than $2 trillion in investments, China is slowly turning Africa into what Howard W. French described as China's Second Continent (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015).

"Sensing that Africa had been cast aside by the West in the wake of the Cold War, Beijing saw the continent as the perfect proving ground for some Chinese companies to cut their teeth in international business," French wrote.

It certainly did not hurt that Africa was also the repository of an immense share of global resources — raw materials that were vital for China's extraordinary ongoing industrial expansion and its across-the-board push for national reconstruction.

China's aggressive expansion into Africa may have solved some of the problems of the old continent while enriching the country's construction companies in the process. But it has yet to help solve China's growing economic problems.

The slowdown in economic growth and falling prices are on top of the list. For the second quarter of 2023, the Chinese GDP grew at an annual rate of 6.3%, up from a 4.5% growth in the first quarter but well below market estimates of 7.3%. And the situation could look far worse if it wasn't for last year's weak numbers due to lockdowns in large cities.

Meanwhile, China's PPI dropped at an annual rate of 5.4% in June, following a 4.6% fall in May. In addition, the July CPI dropped at an annual rate of 0.3% after a flat reading in June.

Next on the list of China's domestic problems is the blow and the burst of a property bubble, which has already claimed a high-profile business failure, with Evergrande Group — China's top-selling developer — filing for bankruptcy protection in a U.S. court two weeks ago.

Third on the list is the country's debt. Officially, it is a fraction of the U.S., eurozone and Japanese debt numbers: 76.90% of GDP. Unofficially, nobody has a fair estimate.

Thanks to scores of loans from government-owned banks to government-owned enterprises and government-supported land developers. They turn the central and the local governments both the creditors and the borrowers.

A bursting property bubble and mountains of debt could turn China into the next Japan, counting lost decades.

"In many ways, China appears to be about 30 years behind what Japan has already gone through," Matt Shoemaker, former intelligence officer at the Defense Intelligence Agency, told International Business Times.

"In 1950, Japan had a massive young population, just like China did in 1980. Japan then benefited from decades of explosive growth that even outpaced the United States," he explained. "Fears were rampant on Wall Street in the 1980s and early 1990s that the Japanese economy was going to overtake America as the largest in the world. The closest Japan got was in 1995 when its economy was about 73% the size of America's — a similar size to China's 76% of the U.S. economy today in 2023."

A Japanese style of prolonged stagnation will worsen China's fourth problem: the failure of the country's leadership to share the country's prosperity. Its younger generations have yet to get a taste of it, as they have difficulty finding a job and cannot afford to buy a home, get married and raise a family.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.