A Year After Deep Cuts to Federal Food Assistance Programs, America’s Nonprofit Food Banks Struggle To Fill The Gap

For most of 2013, the Food Bank for New York City dispatched 15 trucks each day, filled with everything from cereal and rice to fresh fruit and vegetables, to help meet the needs of the city’s hungry residents. These days, it sends at least 29.

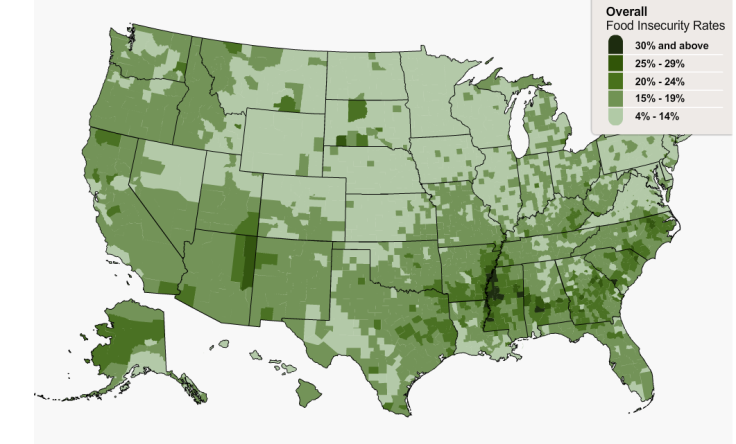

Food pantries across the country always face a squeeze during the holidays, but this year the pressure is more intense. Last November, the federal government scaled back funding for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), widely known for its food stamps. The move left food pantries scrambling to fill the gap amid an already persistent national “food insecurity” problem. In 2013, at least 15.8 percent of American households were “food insecure” according to the United States Department of Agriculture, meaning that they were “lacking reliable access to a sufficient quality of affordable, nutritious food.” That’s up from just 14.5 percent in 2012.

“The biggest resource constraints are food and funds,” Maura Daly, a spokesperson for Feeding America, the largest network of food banks in the country, says. “With the SNAP cuts and more people turning to them for food, either new people or people coming more frequently, that only exacerbates the already strained system.”

For struggling families, food tends to be one of the largest expenses but also an “elastic” one, according to Daly. She says 60 percent of more than 60,000 connected food pantries reported an increase in demand this year, and 36 percent say they don’t have enough food.

“You pay your utility bill and go without eating, or visa versa,” she says, noting that 70 percent of clients say their biggest trade-off was between food and utilities. “And that data was collected prior to SNAP cuts going into effect,” Daly says, noting that even before the cuts, most families receiving food from the network were also SNAP recipients who couldn’t stretch the benefits far enough. Now, based on anecdotal reports, she says many food banks are seeing an increase in recent months. “We’re feeding more people than ever before.”

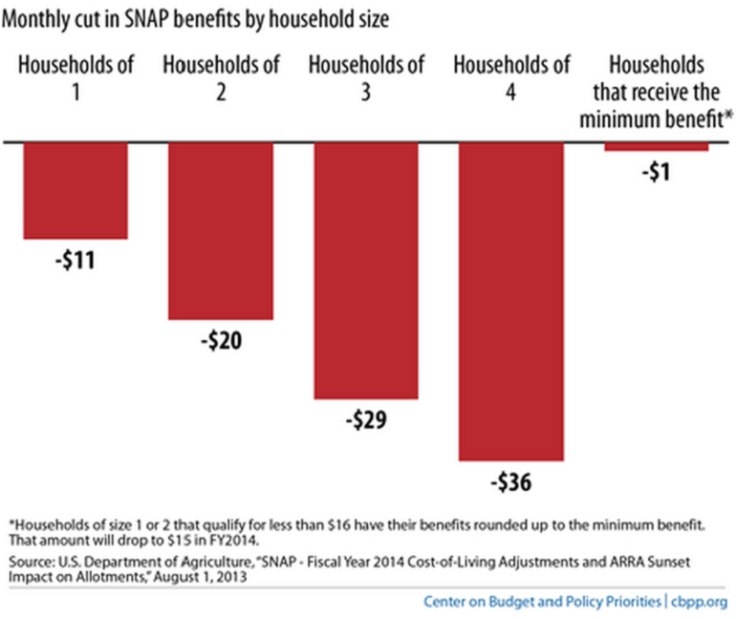

In 2009, Congress agreed to a temporary increase in SNAP benefits as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (also known as the stimulus act). With the aim of helping families struggling in the recession and stimulating local economies, Congress authorized a 13.6 percent increase in monthly benefits starting in April 2009. But the increase was always scheduled to be short term. On Nov. 1, 2013, the extra benefits expired, cutting $5 billion from the program’s funding, which was $82.5 billion in 2013.

New assistance payments were pegged to the Thrifty Food Plan, which is the amount necessary for a family of four to purchase and prepare food at home, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Starting in November of last year, a family of four that once received $668 a month started receiving just $632 per month. That $36 per family difference has hit the nonprofit sector hard.

“The SNAP cuts that took effect Nov. 1 represent the biggest systemic factor reducing the food purchasing power of low-income people,” the Food Bank for New York City said in a recent report. The cuts occurred as other factors such as unemployment actually decreased in the same time period, so while it may have seemed as though America's impoverished needed less help, the reality was that they needed more. The nonprofit organization reported that the majority of its 522 food pantries and 138 soup kitchens were reducing portion sizes and even turning away visitors after an 85 percent increase in traffic, which could increase even more.

“It is likely that more SNAP recipients than ever will turn to Food Bank’s emergency food programs -- a prospect for which the emergency food network is ill prepared. Vulnerable New Yorkers could be left with nowhere to turn for needed food,” the report says.

These glaring statistics made headlines. But big cities aren’t the only places where charities are struggling to cover the gap left by cuts to the program.

“The reality is that SNAP cuts are affecting tens of millions of people across the country in all communities,” Daly says. “There are pockets where things like cuts to SNAP are even more invisible,” she says.

While California, Texas, Florida and New York saw the biggest losses from SNAP cuts, losing between $300 million and $450 million each in fiscal year 2014, some of the hardest hit states were those with smaller populations, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

While metropolitan areas such as New York are densely populated with large numbers of people without food, the struggle is sometimes harder far from cities, where good food is more expensive and harder to access. She says more than half of the counties with the highest rates of food insecurity are rural.

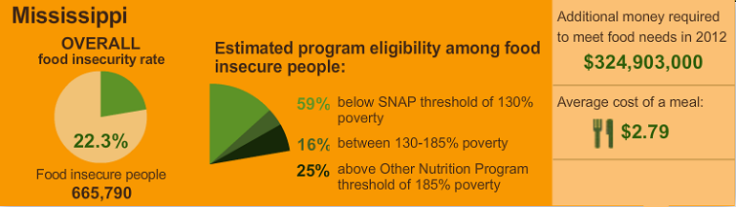

Mississippi, for example, only saw about $70 million worth of cuts. But 22 percent of its population was receiving SNAP benefits to begin with, the highest rate in the county. The state also has some of the highest rates of poverty and obesity in the United States.

“People were struggling before, and with the benefit cuts we’ve seen this year they’re struggling even more.” says Kathy Clem, executive director of the Good Samaritan Center in Jackson, Mississippi. “Since the beginning, we’re seeing 100 more people every month,” she says.

She says that since the SNAP cuts took effect, the food pantry has seen a 30 or 40 percent increase in people coming for meals, and that she often finds herself distributing food to clients who come by for other reasons. For example, the center also runs a service that distributes clothes to families in need. Lately, these clients have been in great need of extra food as well.

“I run a nonprofit, and I have to balance my budget,” she says. “But how do you explain that to a family that’s seen their resources drop so fast?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.