Yo-Yo Sales: For Subprime Borrowers, Car Contracts With Many Strings Attached

Jesus Soria hadn’t planned on buying a car the evening he stopped in for an oil change at a Toyota dealership in North Austin. After all, he knew his credit wasn’t good. But a sales team convinced him to tour the used car lot anyway. Soon after, as he sat in an orange-cushioned chair in the finance manager’s office, he received some exciting news: One bank, he was told, would approve him for financing.

The next day Soria returned, placed the $1,000 down payment, signed the papers, and drove off the lot in a silver 2009 Toyota Camry.

That was in October of 2013. But over the following months, the dealership summoned him back to sign two more contracts on the car. In January, the finance manager called Soria back yet again. This time, he was told he’d have to put down an additional $666, and buy a $2,000 service contract — or give back the car.

“They know you need something and they want to make you feel like they’re the only one who can help you — but it’s going to be under their terms,” says Soria, 27, who goes by the name Jesse.

The January incident in the finance manager’s office — which the dealership denies took place — is now at the center of a lawsuit Soria filed against Charles Maund Toyota in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas. After refusing to pay the additional amount he says the dealership asked for, and requesting his down payment back, Soria claims he received a series of threats and harassing phone calls. He says ultimately the dealership filed a false police report, accusing him of felony auto theft and fraud. He’s seeking damages in connection with the Truth in Lending Act, deceptive trade practices, and defamation, among other claims.

The suit has been fiercely contested by the dealership. An attorney for Charles Maund Toyota, Brian Bishop, says the company was trying to help Soria get financing, but none of the three contracts Soria signed could be sold to a lender because of his credit history. The dealership claims that each contract offered Soria better terms, and that Soria was “interested and willing to sign a new contract that offered him better terms,” says Bishop.

Bishop says the dealership never told Soria he had to buy more products in order to keep the car. The dealership has also countersued Soria for fraud and breach of contract.

The account Soria outlines in his lawsuit is strikingly similar to scores of “yo-yo” sales that take place on American car lots every year. They’ve plagued auto buyers for decades – especially those with poor credit and low incomes. In a typical scenario, a consumer leaves the car dealership believing the deal is final. But if the dealership can’t sell the contract to a bank on profitable terms, it may try to re-write the terms and call the buyer back in to sign new papers — often at a high cost to the customer.

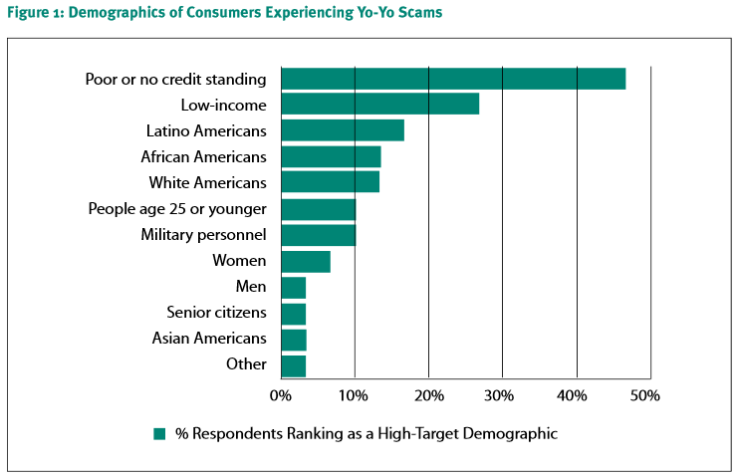

Data on the prevalence of yo-yo scams is scarce, but in a 2012 survey of consumer attorneys and professional organizations, the Center for Responsible Lending found that among 2,100 clients dealing with auto finance problems, 27 percent had experienced a yo-yo scam in the course of a year. Of that group, nearly half of those clients had poor, or no, credit standing. The sales stem from a common industry practice called “spot delivery.” It essentially means putting a customer in a car “on the spot” – before the dealer has won final approval from a third-party lender.

While yo-yos are a long-running scourge, experts say they are often used to target customers who fit squarely within today’s booming market for subprime auto loans. Lending to borrowers with riskier credit histories dropped during the recession, but it's now climbing quickly. Subprime origination volume reached $20.6 billion during the second quarter of 2014, compared with $10.9 billion in the second quarter of 2010, according to a recent analysis by Loomis, Sayles & Co.

On Wall Street, demand for bonds backed with subprime auto loans has soared, from a low of $2.2 billion in new-issue volume in 2008, to $21.5 billion in issuance value in 2013, according to an October research report by Wells Fargo. The bank projects 2014 levels will hit $25 billion.

Amid the boom, regulators, including the Department of Justice, are probing the subprime lending units of companies such as GM Financial and Santander Consumer USA. Meanwhile, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau recently announced plans to supervise nonbank auto lenders – the very companies that buy customer contracts from dealerships.

Earlier this year, the Federal Trade Commission took enforcement action against a national subprime auto lender for allegedly overcharging consumers and using illegal debt collection tactics.

“We are taking reports about yo-yo financing seriously, and it’s something on our radar screen,” says FTC staff attorney Mark Glassman. “A consumer who leaves a dealership with the belief that they understand all the terms of the transaction, and find them to be acceptable, ought to be able to rely on that,” he says.

In today’s lending environment, consumer advocates say yo-yo sales deserve more regulatory scrutiny. Subprime customers are desperate for financing that will give them access to transportation, says Earl Stewart, a Florida dealership owner and author of the book “Confessions of a Recovering Car Dealer.”

“They are totally at the mercy of that salesman that says, I can get you financing, and I can get you a car,” says Stewart, adding: “When they’re called and told to come back and sign another contract, they’ll come back.”

Often, car-buyers aren’t in a position to say no when dealers present them with new terms such as higher interest rates, additional finance charges or a co-signer requirement. And they are frequently told their down payment, or trade-in, is non-refundable, according to Chris Kukla, senior counsel with the Center for Responsible Lending.

Industry representatives such as the National Automobile Dealers Association (NADA) say spot delivery ultimately provides an important service to car-buyers. “It’s a great convenience to consumers who might not be able to complete a transaction during regular business hours, whose only free time is nights or weekends, when finance sources are unavailable to complete transactions,” says Jonathan Collegio, NADA's vice president of public affairs.

NADA, which represents some 16,000 dealerships, "condemns fraudulent transactions of any type," including "fraudulent yo-yo transactions," says Collegio.

Consumer attorneys and 31 states attorneys general, view the pitfalls of spot delivery differently. Ian Lyngklip, who runs Lyngklip & Associates Consumer Law Center in Michigan, likes to use an analogy to explain the connection between spot delivery and yo-yos: Imagine you go to the grocery store. You pay for food, and once you reach the parking lot, you start eating a banana. Then a clerk chases after you and says, “Sorry, your financing fell through. We’re taking back the food.”

“The concept is absurd,” Lyngklip says.

Wheeler Dealers

Earl Stewart is celebrating his Florida car dealership’s 38th anniversary this month. Looking back on his career, Stewart is not always proud of the dealer he used to be.

“I would spot-deliver a car knowing I didn’t really have credit approval, and I would maybe have to get the car back,” he says.

Stewart now considers himself a consumer advocate. He hosts a call-in radio show and writes a weekly column about car buying. “You’re at the mercy of the dealer,” Stewart says. “All you know is, he is telling you what the bank says.”

Car dealers, Stewart explains, don’t like to hang onto a contract, and accept the customer’s monthly payments. They want to sell it to a bank so they can receive a quick lump sum. Selling the contract to a bank or a nonbank lender is crucial, because dealers also have to pay back the money they borrowed to buy their inventory. Stewart, for example, borrows from Bank of America to purchase his inventory, and he owes the bank $10 million at any given time. As soon as he sells a car, he is supposed to repay BofA. In turn, the bank periodically audits his inventory, also known as a "floor plan." Stewart gets audited only twice a year because he has good credit and a long relationship with the bank. But that varies from dealer to dealer – it could be weekly, or monthly, and utterly by surprise.

“When they do a floor plan audit and the car’s not there, they won’t leave the dealership without a check in hand for that car,” Stewart says. “It’s complicated, and it’s a lot of money,” he adds. “And a typical customer is clueless as to what’s going on.”

The dynamics add urgency and pressure to a yo-yo deal, says Lyngklip, because dealers risk “violation of their contract with their own financing company.” Also, he says, banks and finance companies generally reserve the right to back away from a customer’s contract — even one they have approved — after they’ve had more time to review it.

Dealerships, he says, “are engaging in effectively a three-way negotiation in which only one of the parties has all of the information.” But, he says, customers should be able to rely on the documents they sign.

State prosecutors view the practice as highly problematic. In 2011, the Federal Trade Commission, which regulates car dealerships, hosted a series of roundtable discussions about auto lending with consumer attorneys, car industry representatives, and law enforcement officials. Bill Brauch, the director of the consumer protection division in the Iowa Attorney General’s office, and chair of the automobiles working group for the National Association of Attorneys General, spoke on one of the panels.

“Obviously, if you have a situation where a consumer is trapped,” Brauch said, “where they believed they had financing, they believed that they had a deal, and they got a call that said, ‘Come on back, and you're gonna have to work this out with us,’ it's a very difficult situation -- particularly if the trade-in that the customer had was sold.” He added: “This is an area where a baseline protection from the federal government is warranted.”

It’s hard for consumers in these situations to stand up for themselves, says Rashad Blossom, who operates a consumer law practice in Charlotte, North Carolina. They’ll often sign a less-favorable deal to avoid being embarrassed in front of their family or friends, or because they feel intimidated.

For one of Blossom’s clients, Cain Victor Wilson III, of Rowan County, North Carolina, the case comes down to alleged physical harm. Last year, after filling out an online credit application, Wilson purchased a used Kia Optima from a Suzuki dealership. Wilson made it clear, according to his attorney, that he would not provide a co-signer on the loan.

Several days after signing the contract, the dealership began calling both Wilson and his fiancée about needing a co-signer. Wilson said no and reminded the dealership that “he had provided all the requested financial information, that the contract was signed, and that the deal was done,” according to a civil lawsuit Wilson filed in the state court of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

Wilson’s complaint describes what happened next: According to the filing, on July 15, 2013, two men showed up at his workplace -- a supplies company -- and told him the dealership had sent them to “get the car.” Wilson went to his car to make a phone call from the driver’s side, when one of the men “got in on the passenger side, reached his left arm around [Wilson’s] neck and began attacking and violently choking” him, the complaint states.

The dealership admits in court papers that one of the men contacted Wilson about needing to “take possession of the vehicle due to plaintiff’s failure to comply with certain terms of his contract,” and also entered the passenger side of the car. In its filing, the dealership denies the attack Wilson described. Jeffrey Kuykendal, an attorney for the dealership, Planet Automotive Group, declined to comment for this story, citing the ongoing litigation.

Following the alleged attack, Wilson’s complaint states that the dealership accused him of defaulting on his loan payment, and succeeded in repossessing the car with his belongings inside, including two baby seats for Wilson’s children, a wallet containing his $1,200 rent payment, and memorabilia from his wedding, the lawsuit says. The dealership denies those allegations, according to its filing.

Blossom tells IBTimes that as a result of his injuries, Wilson missed nearly three months of work last year, and has been unemployed since March of this year.

'I Just Start Crying'

The house in East El Paso overlooks the city’s lower valley and, to the west, the edge of the Franklin Mountains. Low houses, rock gardens and manicured evergreens line the street where Jesse Soria lives now, with his older sister Carol. He parks his car – a blue-gray Ford Fusion – in front of her two-car garage, next to some low palms. He’s staying in his cousin’s room while finishing his bachelor’s degree at the University of Phoenix and working as a sales executive for AT&T.

One evening in September, after he and Carol finished a dinner of chicken chipotle, he sat at the glass table in the kitchen. On his iPhone, he pulled up a picture of the Mercedes he’d bought at a California dealership about five years ago. The hood gleams in the sun, the front grill sporting a bright-red bow. Soria bought it for $16,000 and financed the purchase. “I had really good credit,” he says. When the car ran into multiple problems, though, he couldn’t keep up with the cost of repairs and the payments. Finally, he had to call the dealership and tell them where they could pick it up. Because of the repossession, he figured he wouldn’t qualify for financing again -- at least not for a long time.

So, Soria says, he felt particularly grateful to the finance manager, Victor Martin del Campo, who told him last year that he’d been approved to buy the silver Camry. He called his sisters and his mom from the car lot, and posted about his new purchase on Facebook. He sold the Celica that he’d bought from a family friend.

When del Campo asked Soria to return and sign a second contract in November, Soria brought him a bottle of Crown Royal whisky,“to thank him for helping me get a car,” he says. The terms of the second contract were actually better than the first. “Must be your lucky day,” Soria recalls del Campo saying to him.

International Business Times was unable to reach del Campo for comment on the transaction. He no longer works at Charles Maund Toyota. According to the dealership’s attorney, Brian Bishop, del Campo left the company in June of his own accord, and Bishop told IBTimes he was unable to provide contact information for him. Multiple attempts to contact del Campo, including through another former employer, were unsuccessful.

By December, Soria was growing wary. He’d insured the Camry immediately, but still had only temporary tags. When he called the finance company about making his first payment, he was told he wasn’t in the system. Another exchange with the dealership ensued, and the dealership's staff told Soria he’d need to come back one more time -- and sign another contract. He also made the first monthly payment on the new contract— $333.25 — though it wasn’t due until February.

According to Charles Maund Toyota’s court filings, Soria still came out ahead on the third contract, compared to what he signed in October. The new total sales price came out to $16,996, with payments of $333.25 a month for 48 months, versus the $18,351.46 October contract.

But Soria says he was frustrated by the ongoing hassle, and that after signing the third contract, he hoped to never see the dealership again. Then, while traveling in New York over the New Year holiday, he got the next call. Upon his return to Austin in early January, once again, he trooped back to Charles Maund. He waited for del Campo in the lobby, and then followed him back down the hall to the now-familiar office, dingy and small with the one window looking onto the darkened parking lot, which Soria could see from his seat across the desk from del Campo. According to Soria’s complaint, del Campo told him “that in order to keep the 2009 Toyota Camry, he would need to pay an additional $666.00 down, plus purchase a $2,000 service contract on the vehicle.” Charles Maund denies the allegation in court filings.

“He said, that’s the only way the bank’s going to finance you, if you do this,” Soria tells IBTimes.

“And I can’t help it, but I just start crying, because I think, how am I supposed to get to work?” says Soria, who at the time was earning about $13 an hour in an administrative role at insurer Marsh & McLennan. “What am I going to do without a car?”

Soria wouldn’t submit to the new terms. And, according to his complaint, del Campo agreed to pay back his $1,000 down payment and his first monthly $333.25 “on one condition”: that Soria return all the paperwork and previous contracts he'd signed with Charles Maund. (The dealership denies this claim in court papers.)

“That’s when I knew something wasn’t right,” Soria says. “Why would they want the originals if they had their own copy?”

It would be months before Soria saw the check — not until later in the spring, after his attorney first sent the dealership a demand letter and subsequently filed the lawsuit in April.

Soria's discussions with Charles Maund Toyota's staff deteriorated quickly. On January 8, 2014, Soria called the dealership and “asked if the check was ready so that he could return the car,” his complaint states. Afterwards, “Victor Martin del Campo calls Mr. Soria and told him that the Toyota had been reported stolen,” the complaint goes on. “Mr. Martin del Campo then hung up on Mr. Soria without explanation.”

Throughout the litigation, the dealership has consistently denied that del Campo said any such thing. They claim that Soria said he had hidden the vehicle where the dealership “would never find it.”

Soria says that’s not true. And by his account, the alleged threat put him on edge. He recalls thinking, “What if I get pulled over? Am I going to get arrested because they think this car is stolen?”

By this point, Soria had already contacted an attorney. And when he called the dealership once more about his check, and mentioned that he had a lawyer, an employee hung up on him, his suit states.

To guard against further trouble, Soria decided to buy another car -- this time from CarMax. Then, on Jan. 11, he took the Camry in for servicing at Charles Maund. He wanted to be sure to have a voicemail from a service department rep, he says, to document that the car was in good shape. Once he received the message, on January 11, he called the service department, and instructed a staffer to let the dealership know the car was now in its possession.

In court filings, Charles Maund maintains that Soria abandoned the car, never informed the dealership of its whereabouts, and refused to answer calls. The dealership also says it believed at the time that Soria had used a false Social Security number.

Soria and his attorney, Amy Kleinpeter, say he never falsified his Social Security number, and that the dealership had used the original number he provided numerous times to pull Soria’s credit report.

Nevertheless, Soria started receiving calls from a man who identified himself as a “detective” and told Soria “you used another person’s Social Security” number to purchase the Camry, according to a recording reviewed by IBTimes. “You got an option right now. You’re going to get hit with two felonies if you do not want to go ahead and turn this vehicle in,” the man said in a voicemail left on Jan. 14.

“Think of what you need to do,” the man continued. “I will contact you at work and check out where you’re working at.”

The next morning, at 7:24 a.m., the man called again, and left another voicemail. “You want to play games? That’s no problem. Being young is being dumb. That’s no problem,” the man said. “You know I’m trying to work with you. You don’t even want to be man enough to get on the phone and talk.”

That afternoon, Soria’s phone rang again, this time from a phone number marked Austin Police Department on his caller ID. The person on the voicemail identified himself as being with the department. “It is now 12:42. You have exactly 20 minutes to return that silver Camry to Charles Maund, or we’re going to file charges against you.”

That day, Jan. 15, the dealership filed a police report. It lists Soria as a suspect for fraud, and felony auto theft. The report states that the offenses occurred as early as December 13, 2013 — 10 days before Soria signed the third and last contract on the car he thought he had purchased in October.

A New Life

The police never did question Soria about Charles Maund’s accusations. In a report, officers said they found no discrepancy with the Social Security number Soria supplied for the purchase of the car. The dealership, meanwhile, has since sold the Camry to another buyer.

But Soria’s litigation with Charles Maund continues. Since moving back to El Paso over the summer, Soria has had to make the nearly 600-mile drive back to Austin for a deposition. He'll need to go back again next month, for a mediation session both parties agreed to.

One recent Sunday afternoon, Soria puttered about in his new El Paso life. He gathered chiles de arbol from the back garden, and set them down on the kitchen table. He fed his six-month-old Siberian Husky, Red, and spoke to her in the Russian commands he learned earlier this year. He took a seat in the kitchen, with Carol across from him, a manicure kit spread before her, and talked about his plan for starting a business and eventually, buying a house here. He loves this border city.

Turning to the subject of what happened in Austin, though, his easy smile disappears and his face goes blank. Earlier this year, he lost about 30 pounds, he estimates, as he worried about the police and the car situation. In January, his monthly performance score at his old job dropped to about 30 percent, from his normal 95.

He continues to avoid calls from numbers he doesn’t recognize. Seeing a police car on the street reminds him of what happened.

"Nothing is going to fix what happened," he says. "I'm still going to always have that in the back of my mind. It's hard for me to trust people now."

Carol listened and painted her nails. Behind her, through the window, the sun was shining in the backyard where Red plays and where the sound of cars drifts in from Interstate 10 – a road that leads the way, like a very long string, back to Austin.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.