After No Victory, Westminster In A Quandary Over Promises To Scotland

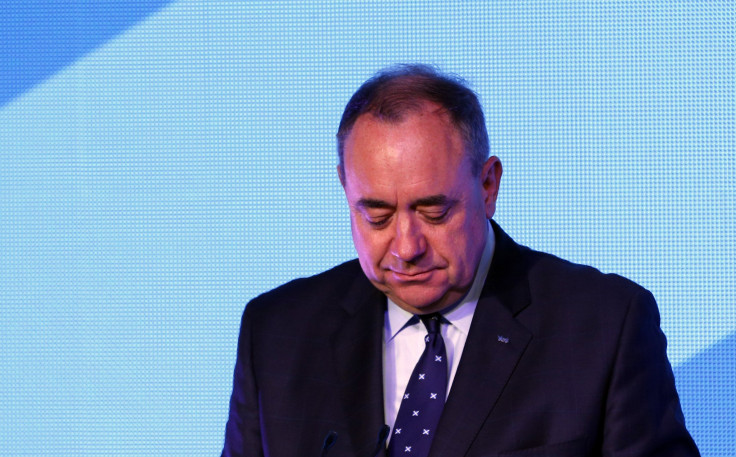

The political fallout from Scotland’s decisive No vote by a margin of 55 percent to 45 percent in Thursday's independence referendum is already being felt: Alex Salmond, the leader of the Scottish National Party, will resign in November. But before Salmond brings the curtain down on a political career spanning nearly 40 years, he will first have to negotiate the transfer of new tax-raising and welfare powers from London to Scotland.

But those powers, promised to Scotland in the final weeks of the campaign, have already raised fierce debate in Westminster, with many Conservative MPs saying they will block any such transfer, known as devolution. That raises questions about whether Prime Minister David Cameron and his coalition government can actually deliver the promises made by the three main parties -- Cameron's governing Conservatives, the allied Liberal Democrats, and the opposition Labour.

“Cameron can sleep easily tonight," said Matthew Feeney, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute in Washington. “But he really does have to follow through. The Scots won’t forgive a government that doesn’t keep its word when it comes to devolution of powers.”

The process to transfer those powers will begin as early as next week. Draft legislation may pass by January, a rushed timeline by comparison with similar reforms in the past.

But many see the new powers for Scotland as a raw deal for the rest of the UK: Northern Ireland, Wales and England. It also brings up the so-called "West Lothian Question": The fact that Scottish MPs can vote on English issues in the UK Parliament, but not the other way round. Westminster backbenchers say they will try to block Scotland’s new powers until that issue can be resolved.

The complex issue has its foundations in the basic fact that Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland all have their own parliaments that deal with some local political decisions, a right that was given, or "devolved," to them by Westminster. England, on the hand, has no parliament of its own and therefore has no devolved powers from the UK Parliament. Instead, English issues are discussed inside the House of Commons by all members. A simple fix, say some, would be to ban Scots, Welsh and Northern Irish members from voting on English issues. However, those decisions regarding England made in Parliament are funded with money coming directly from central treasury funds, unlike the other three countries, which are given Westminster grants.

"England this time will not be fobbed off with third-class devolution or no devolution at all," wrote John Redwood, Conservative MP for Wokingham, England, on his blog. "The Scottish vote and attitudes changes things fundamentally – for England as well as for Scotland."

This rising discontent will be alarming for the three main parties at Westminster, who may turn to history to see how unfulfilled promises of new powers have hurt them in Scotland.

In 1979, Scotland held another referendum on independence, which similarly did not pass. The Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher told voters that if Scotland opted for No, Westminster would transfer some powers back to Scotland, which at that time had none at all. Scots waited 18 years for the promise to be fulfilled, and instead saw austerity budgets dictated from London hurt social spending. They punished Conservatives at the polls, and the party has never recovered: Today it has precisely one member of Parliament in Scotland.

But as the Westminster political establishment has to look back to avoid past mistakes, it will be forced to look forward if it wants to keep Scotland in the United Kingdom. “Seventy-one percent of 16-17 year olds voted Yes. So, it’s certainly is a generational thing,” said Feeney. “Also, (the) 25-35 (age bracket) was almost 60 percent yes. The people that really endorsed staying the union were the older generation, and they will start to die off eventually. Westminster will be looking at that very closely because it shows that if they don’t follow through on a devolution of powers, they are going to have to deal with generations of Scottish voters who will feel let down.”

As he made one of his final speeches as Scotland’s first minister, Salmond fired a last warning to the central government. "We now have the opportunity to hold Westminster’s feet to the fire on the 'vow' that they have made to devolve further meaningful power to Scotland. This places Scotland in a very strong position.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.