Ancient Shell-Less Turtle Species Identified From 228-Million-Year-Old Triassic Era Fossil

Scientists have discovered remains of a rare kind of turtle, one that lived over 228 million years ago in the Triassic era and had no shell – the most common feature of present-day turtles.

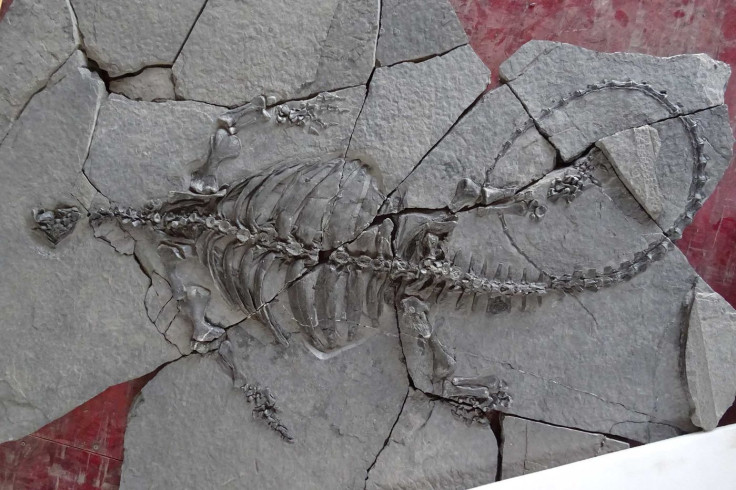

The nearly complete skeleton of the ancient turtle was found by researchers from China's Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in the Asian country’s Guizhou province.

The animal had a toothless beak and Frisbee-shaped body just like present-day turtles, but there were no signs of growing bones that form the shell. Modern turtles use the feature to enclose their vital organs, including the head in some cases, and protect themselves.

"This creature was over six feet long, it had a strange disc-like body and a long tail, and the anterior part of its jaws developed into this strange beak," Olivier Rieppel, one of the researchers involved in the work, said in a statement. "It probably lived in shallow water and dug in the mud for food."

As no such turtle has been described in the books of science, the animal has been classified as a completely new species. It has been named Eorhynchochelys sinensis, which means the ‘Dawn turtle with a beak from China’.

The shell and the beak are two important elements of turtle evolution. However, their origin and development have been quite a puzzle for scientists. For instance, another primitive turtle that existed around the same time had a partially developed shell but no beak.

"The origin of turtles has been an unsolved problem in paleontology for many decades," Rieppel added. "Now with Eorhynchochelys, how turtles evolved has become a lot clearer."

This, as the team described, is the case of mosaic evolution, where animals develop physical features at different times, despite living during the same period. Due to this kind of evolution, traits like beaks and shells evolved independently of each other and primitive turtle species featured differently developed combinations of shells and beaks.

Simply put, physical traits didn’t evolve in a straight line. Some turtles got shells, others got beaks, which eventually led to the development of both these traits in the same animal.

"This impressively large fossil is a very exciting discovery giving us another piece in the puzzle of turtle evolution," Nick Fraser, another author of the study, said in the same statement. "It shows that early turtle evolution was not a straightforward, step-by-step accumulation of unique traits but was a much more complex series of events that we are only just beginning to unravel."

Apart from this, the team also found signs that confirmed Eorhynchochelys was a diapsid – the reptile group that had two openings on the side of their skulls. For years, scientists wondered if ancient turtles were part of the same group, and the new discovery solved that mystery.

"With Eorhynchochelys's diapsid skull, we know that turtles are not related to the early anapsid reptiles (those without openings), but are instead related to evolutionarily more advanced diapsid reptiles,” Rieppel concluded. Modern-day snakes and lizards also evolved from the diapsid population.

The study titled, "A Triassic stem turtle with an edentulous beak," was published August 22 in the journal Nature.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.