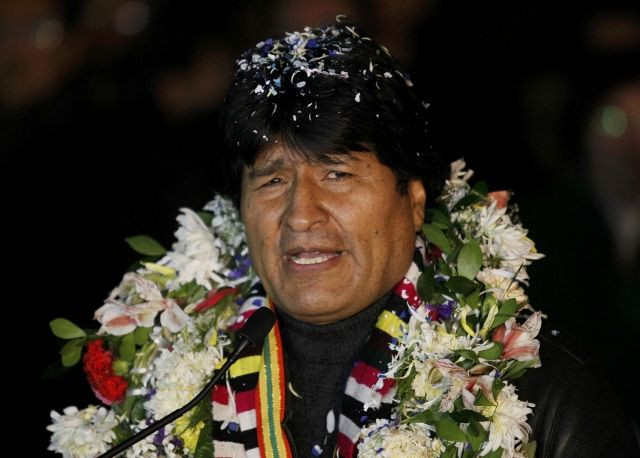

Bolivian Census Highlights How Changes In Bolivian Demographics Might Affect President Evo Morales’ Power Base

President Evo Morales can pride himself in being Bolivia’s first indigenous ruler. A strong supporter of the rights of Bolivia's historically downtrodden native people, he has become a sort of iconic figure for the world's leftists and has made no secret of his opposition to U.S. policies. But as demographics in the country are changing, he might find himself with a much smaller power base. The 2012 census, whose results were disclosed Tuesday, shows that the majority of the Bolivian population calls itself mixed-race, as opposed to indigenous, as Morales had asserted in January. People who identify themselves as indigenous dropped by a whopping 18 percentage points from 2001.

Both the UN and the World Bank have endorsed the official results of the census, according to Spanish newspaper El País -- but some Bolivians are skeptical and demanding an audit.

The issue lies in the difference between the official numbers and the preliminary results that Morales announced in January. The president calculated that 10,329,000 Bolivians lived in the country, with Santa Cruz being the most populated province. The official number counted 10,027,000 inhabitants, with a 1.71 percent annual growth. The difference of 300,000 affects the provinces of Cochabamba, Santa Cruz and La Paz, as reported by Bolivian newspaper La Razón -- La Paz has 28,000 inhabitants fewer than anticipated, and Santa Cruz jumps to the top as the most populous city in Bolivia, with just over a million.

“My big mistake was to believe what the press was hinting at, and rushing the results,” said Morales. “But I always said the results were preliminary.” He added that there was no intention of manipulation in his earlier statement.

The importance of the difference in the numbers lies in how funding and seats in Congress are allocated, since provinces get different numbers of members, and aid, depending on population. The most populous provinces -- Cochabamba, La Paz and Santa Cruz -- will receive two-thirds of national funding, and the other six the rest. The possible loss of economic and political privileges caused protests in some provinces, and petitions demanding to establish who is to blame.

Another surprising result of the census was the racial distribution of the country. Compared to the 2001 census, which found that 66.4 percent of the population was indigenous, the latest report pointed at a mainly mixed-race population, although the census avoided that term, considering it racist. Almost half of the population, 40.3 percent, identified themselves as “none,” meaning that they did not consider themselves part of any of the 36 indigenous groups that live in Bolivia. Most of these “none” people live in the three most populated provinces, which also have the highest importance in elections -- meaning that Morales might be losing his appeal as “the most Bolivian president.”

On the other hand, 48 percent of Bolivians did declare themselves indigenous, with the Quechua and Aymara ethnic groups making up 80 percent of them.

Morales himself was surprised by the result. “I can’t say if it’s due to a less classist society, or just a more colonized mentality,” he said.

Other census results were encouraging: More than 95 percent of the population is literate, 70 percent own a house, and 83 percent have finished elementary school.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.