Calls For Action After Gulf Of Guinea Piracy Surge

The Mozart was 200 miles off Nigeria's coast when the pirates made their assault, their speed boat cutting through the Gulf of Guinea's waters to outpace the container ship.

Armed men scrambled onboard as the Turkish crew locked down in the ship's "citadel" secure area.

For six hours, pirates used the ship's power tools to rip open the security door. They shot one sailor dead and kidnapped 15 more, ferrying them to Nigeria's coast for ransom.

The January attack described by crew and shipping sources was one in recent cluster of raids far off Nigeria's coast where commercial vessels now face a more complex threat.

Pirates have long been a risk in Gulf of Guinea, a major shipping route stretching from Senegal to Angola, with Nigerian gangs carrying out most attacks.

But shippers say pirates now raid farther out, and their violence and sophisticated tactics are prompting pleas from shippers for a more robust foreign naval presence like the mission to curb Somalia piracy a decade ago.

"My patience has run out," Jakob Meldgaard, CEO of major Danish tanker fleet operator TORM told AFP. "We have to confront the obvious, we do not have control of the situation."

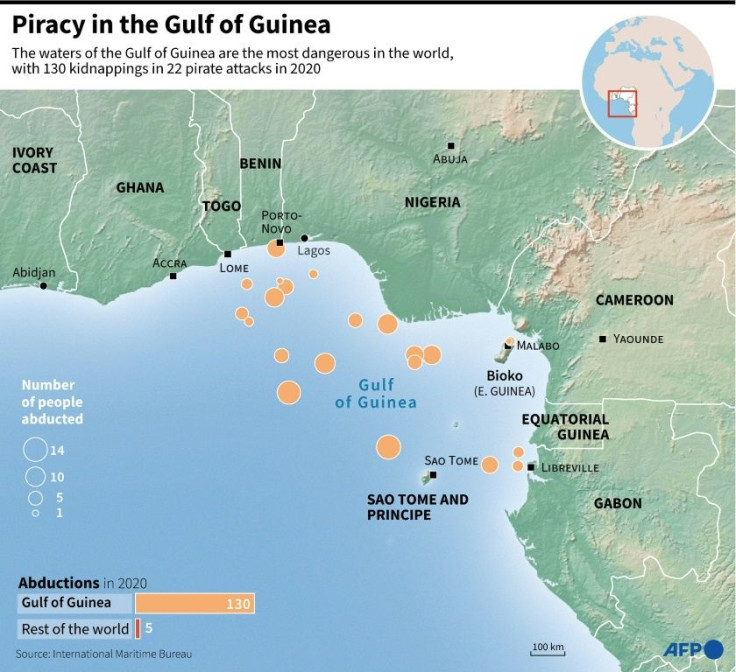

Gulf of Guinea accounted for more 95 percent of all maritime kidnappings last year -- 130 out of 135 cases, according to the International Maritime Bureau (IMB), which monitors security at sea.

Just this year has seen 16 acts of piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, according to Dryad Global maritime security consultancy.

Shippers and western military officials say increasingly pirates target a "soft spot" between Nigeria's naval capacity and the limited foreign presence beyond its waters, where gangs know a response is less likely.

The Mozart attack showed pirates could spend enough time onboard to breach the "citadel" and kidnap crews without fear of interdiction, said Dryad partner Munro Anderson.

"They worked to break the doors for six to seven hours," Turkish chief engineer Suha Tatligul told Turkey's maritime magazine after he escaped. "I hid in a dark area. They opened fire as soon as they broke inside."

The Turkish sailors were released over the weekend after three weeks in captivity.

Nigerian pirates this month briefly used a hijacked Chinese fishing vessel as "mother ship" to stay out to sea longer and carry out a spat of attacks off Sao Tome, Dryad said.

Shippers want change quick. Since December, the Danish, Indian, Cypriot shipping lobbies have all called for action.

Denmark's industry, with an average 30 to 40 vessels in the Gulf of Guinea a day, is lobbying for "coalition of the willing" to operate a naval deterrent while helping local forces build capacity.

"These pirates are professional, they have the best equipment, they are dressed in military uniforms and they attack our ships far out," one shipping source said. "We need to do something else here."

Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea has its roots in Nigeria's Niger Delta where oil wealth has failed to reach local populations and deep poverty has stoked militancy and armed unrest.

Gangs speed out from swamps to raid passing vessels, snatch crews and spirit them back to Nigeria's shores.

Nigeria has spent nearly $200 million on its naval Deep Blue project, investing in surveillance equipment, vessels and aircraft to better secure its waters.

Nigeria's maritime agency NIMASA chief Bashir Jamoh expects the system to be operating next month and wants more regional cooperation.

"Our solution to the insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea must be homegrown by cooperating among ourselves," Jomah told a virtual summit.

Last year, Nigeria also carried out its first ever trial under a new piracy law.

Newly appointed naval chief of staff Rear Admiral Awwal Zubairu Gambo has called on commanders to clear pirate bases, while demanding a crackdown on corrupt navy officials working with gangs.

Just in January, a Nigerian patrol helped rescue a Maersk container ship boarded off the coast.

"They are better than the rest of the region, but they are not quite there yet," one Western military source said of Nigeria's capacity.

EU nations like the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Portugal and France often have naval vessels operating in the Gulf -- two or three ships are present a day.

In November, the Danish vessel TORM Alexandra was boarded in an early morning raid while nearly 200 miles off Nigeria.

A nearby Italian frigate managed to dispatch its helicopter to fly over, sending the pirates fleeing in their boat.

But the Gulf of Guinea may be less of a priority for a costly long-term foreign naval presence as in the Horn of Africa or the key oil route of the Straits of Hormuz.

Local reactions to more foreign naval presence may also be key.

"They may be reducing piracy, but they will also be interfering in sovereign nations," said Max Williams at Africa Risk Compliance maritime security agency specialising in West Africa. "They also will not be addressing the root causes."

Nigeria's Niger Delta is a combustible mix to solve -- ex-militants, illegal oil trade, illicit fishing and poverty combining in an underdeveloped region.

"No jobs, no money, no hope," said Fegalo Nsuke, a Niger Delta community leader. "The youths see piracy as a way out."

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.