Ceres: NASA’s Dawn Spacecraft Closes In On Dwarf Planet, Photographs Strange Crater

After spending more than three years in the vicinity of Ceres, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft shifted to a new orbit, one that brings the probe closer than ever to the dwarf planet and provides an unprecedented opportunity to observe and understand strange features seen on the distant body.

Ever since approaching Ceres, Dawn has relayed a massive chunk of scientific data and images showcasing the dwarf planet in its full glow. The photographs revealed strange bright spots on the surface, which drew immediate attention from the scientific community.

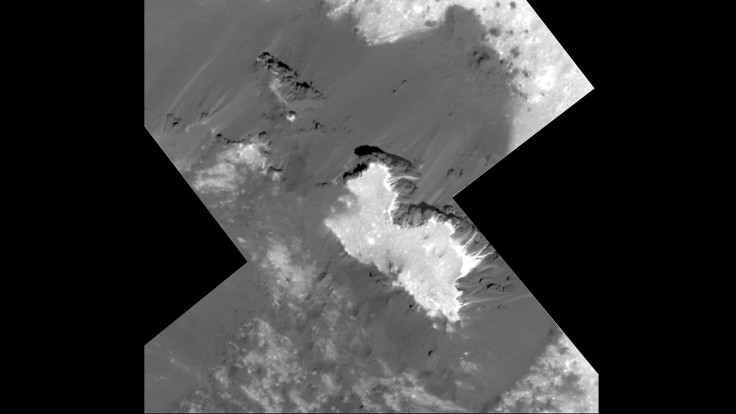

NASA scientists have been analyzing the data to delve into these features, but when Dawn reached its new orbit on June 6, coming just 35 kilometers (22 miles) above surface, the agency got a chance to take a better, closer look at a 90km-wide crater called Occator – one of the sites where the bright deposits were seen.

“Acquiring these spectacular pictures has been one of the greatest challenges in Dawn's extraordinary extraterrestrial expedition, and the results are better than we had ever hoped,” Marc Rayman, Dawn’s chief engineer and project manager, said in a NASA statement. “Dawn is like a master artist, adding rich details to the otherworldly beauty in its intimate portrait of Ceres.”

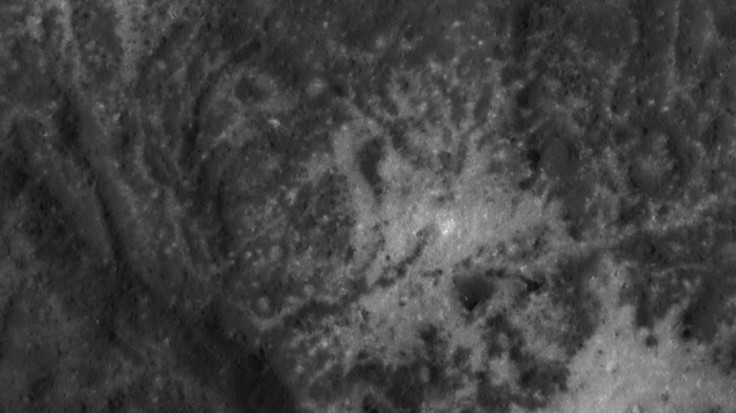

The images taken from the lower-than-ever orbit brought the crater into sharper focus, particularly the deposit called Cerealia Facula near its center. Previous observations from the spacecraft’s visible and infrared mapping spectrometer revealed that these deposits, featured in a pronounced depression, are made up from sodium carbonate. These are just like the deposits seen on Earth and possibly the largest outside our planet, too.

However, the origin of the material is still a matter of debate with two theories in consideration. One suggests that the material was exposed to the surface from a shallow, sub-surface reservoir of mineral-laden water, while the other indicates that salt-rich liquid water from deeper parts of the planet emerged through vents and evaporate, leaving just the bright carbonate deposits behind.

The eastern side of the crater also features similar bright speckles, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany stated while revealing different sections of the crater. The institute, which provided framing cameras for Dawn, also showcased signs of landslides from the northern and eastern rim of the crater. This, as the team said, suggests that some material has been moving down the slopes, while the rest remains stuck in between.

That said, scientists hope that future shots delivered by Dawn will provide more insight into these deposits and how they came to be. The findings might even provide crucial details regarding the composition and sub-surface of the small planet.

"We now hope to understand how the bright deposits outside the crater center came about - and what they tell us about Ceres' interior," Andreas Nathues from the institute stated in another statement.

The complete catalog of images taken by Dawn from its new orbit is also available online.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.