Dehydration By Not Drinking Enough Water Affects Brain, Performance At Work

Dehydration — the situation where the amount of water in the body goes way below required levels — is known to create a lot of trouble, including problems like weakness, tiredness, and headache. It leads to several physical and mental effects, but if a new study is anything to go by, staying dehydrated at work can swell an individual’s parts of the brain and endanger his/her occupational safety.

Be it a regular desk-based job, manual labor around heavy machines, or competitive sports, people often forget to drink water. This results in dehydration, which can then impact their work performance. Researchers from Georgia Institute of Technology conducted an experiment with 13 participants to better understand how the performance falls in such cases as well as any neural changes related to the same.

As part of the project, the volunteers were asked to perform a simple repetitive exercise for 20 minutes, one in which they had to punch a button every time a yellow-colored square appeared on the screen. However, they had to perform the monotonous task while being subjected to different conditions — with variable levels of heat-stress, exertion combined proper hydration or the lack of it.

"We wanted to tease out whether exercise and heat stress alone have an impact on your cognitive function and study the effect of dehydration on top of that," Mindy Millard-Stafford, the principal investigator of the experiment, said in a statement.

The findings of the work revealed that the work performance of a subject, who was relaxed and hydrated declined after 20 minutes, while those who were subjected to heat and exertion alone demonstrated a much quicker decline in performance. The case worsened as the dent in performance was twice as deep when the subjects were under the impact of all stressors, including dehydration.

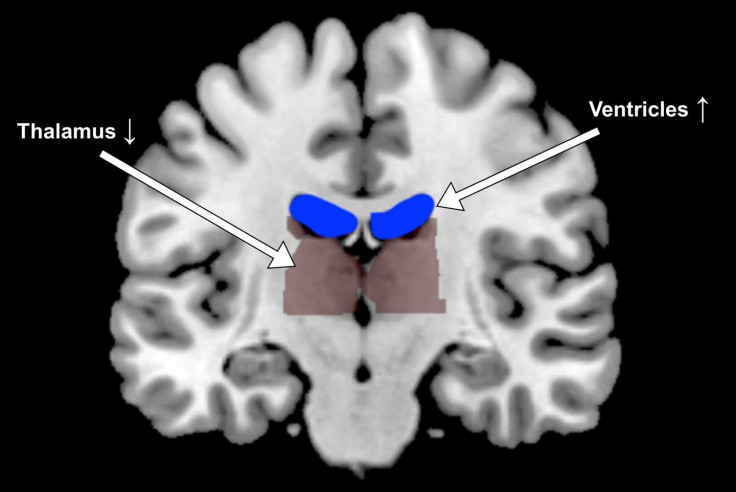

But that wasn’t the only finding. In the scans of the subjects, the team noted some changes in neural activity and parts of the brain. Essentially, when the subjects performed a range of exercises under the impact of heat to gear up for the monotonous button-pressing task, the structure of fluid-filled spaces called ventricles at the center of their brains changed.

When the exertion was combined with proper water support, the ventricles contracted, but when the subjects were dehydrated and there was no water to drink, the ventricles expanded.

"The structural changes were remarkably consistent across individuals," Millard-Stafford added. "But performance differences in the tasks could not be explained by changes in the size of those brain areas."

Among other things, the researchers also noted changes in the firing of neurons. "The areas in the brain required for doing the task appeared to activate more intensely than before, and also, areas lit up that were not necessarily involved in completing the task," first author Matt Wittbrodt said. "We think the latter may be in response to the physiological state: the body signaling, 'I'm dehydrated'."

This, as the researchers described, highlights the risk of being dehydrated at work or while performing at competitive sports. Moving ahead, the team hopes to gain more insight into the effectiveness of electrolyte drinks for preventing dehydration in hot settings and maintaining occupational safety, particularly around heavy machines.

The study was published Aug. 20 in the journal Physiological Reports.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.