Do Octopuses Have Dreams? Tiny Ones, Probably

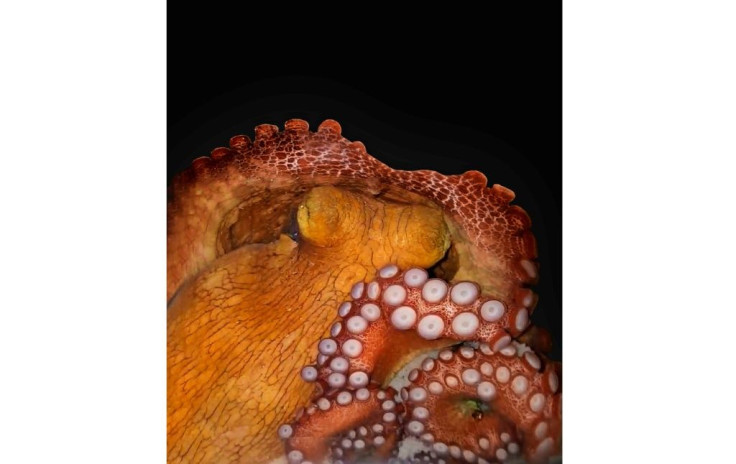

An octopus named Marshmallow lies at rest at the bottom of her tank, suddenly shifting in color from a pale white-green to brown and then orange, as her muscles twitch, suckers contract and her closed eyes shift around.

This moment was captured in remarkable footage shot by scientists in Brazil, who published a new study in the journal iScience on Thursday that says the sophisticated cephalopods experience at least two different types of sleep.

One of these states, which they dubbed "active sleep," is akin to rapid eye movement (REM) in mammals, birds and some reptiles -- raising the intriguing possibility that, like humans, octopuses experience dreams.

"Octopuses are unique in terms of their complexity, both behavioral and neural," senior author Sidarta Ribeiro of the Brain Institute of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil told AFP, noting they have the most complex brains of any invertebrates.

"But they're nevertheless very different from us."

To explore the question of octopus sleep patterns, the researchers continuously recorded four octopuses in their tanks over several days, then went back to analyze the footage.

They found during "quiet sleep," the animals were still, with pale skin and their pupils contracted to a slit. During "active sleep," however, they dynamically changed their skin color and texture, noticeably heaved and twitched, and their eyes moved around.

The pattern was cyclical, with the quiet period lasting around six or seven minutes and followed by an active cycle lasted about 40 seconds.

The cycle might then repeat, or the octopus could wake up, but usually fell back asleep 30 to 40 minutes later. All told, their slumbers take up a quarter of the day.

To establish whether these states really represented sleep, the researchers devised visual and tactile stimulation tests, the paper's first author, graduate student Sylvia Medeiros told AFP.

The first test involved playing a video of a crab on a screen that was placed next to the octopuses.

"When they are awake, because crab is a natural prey, they try to attack," she said. But they didn't try to pounce in the two states where they were presumed sleeping.

In the second test, they struck the octopus tanks with a rubber hammer, with the animals physically reacting and changing their color when awake, but not when asleep.

Learning more about what makes us similar to octopuses, whom our species diverged from 500 million years ago, can shed new insight into our distinct evolutionary paths, said Ribeiro.

"If we see a similar phenomenon, in this case, a sleep cycle comprising quiet sleep and then active, it's most likely due to convergent evolution," he said, meaning our two species independently evolved the same biological mechanisms.

That in turn sheds light on the evolutionary pressures that shaped this behavior.

For mammals, REM sleep represents a time of memory consolidation and triggers a variety of molecular mechanisms that have a restorative effect on brain health and cognition.

The authors think this could be the case for octopuses too.

Most human dreaming also comes during REM sleep -- so might this also be the case for the eight-limbed molluscs?

"We cannot affirm it for sure," said Medeiros.

But if they do, it's unlikely to be similar to the complex narratives we can experience, given how short the active phase is for octopuses, she added. "It should be more like small video clips, or even gifs."

The color patterns the octopuses form on their skins during sleep could offer a window into their minds, as they can mirror patterns they exhibit while they are awake.

For example, the "half and half," where they are black on one side and white on the other, is sometimes seen during courtship -- so might an octopus that displays this pattern during sleep be dreaming of romance?

Maybe, but it's too early to say, said Ribeiro, and the subject of future research.

The team next hopes to find ways to record octopuses' neural data -- a tricky proposition given they are moving around in water -- and to learn more about the role sleep plays for the animals' metabolism and cognition.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.