Emissions Fell Record 7 Percent In 2020: Study

Carbon emissions fell a record seven percent in 2020 as countries imposed lockdowns and restrictions on movement during the Covid-19 pandemic, the Global Carbon Project said Friday in its annual assessment.

The fall of an estimated 2.4 billion tonnes is considerably larger than previous annual record declines, such as 0.9 billion tonnes at the end of World War II or 0.5 billion tonnes in 2009 at the height of the financial crisis.

The international team of researchers behind the report said emissions from fossil fuels and industry would be around 34 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent this year -- still a significant chunk of Earth's remaining "carbon budget".

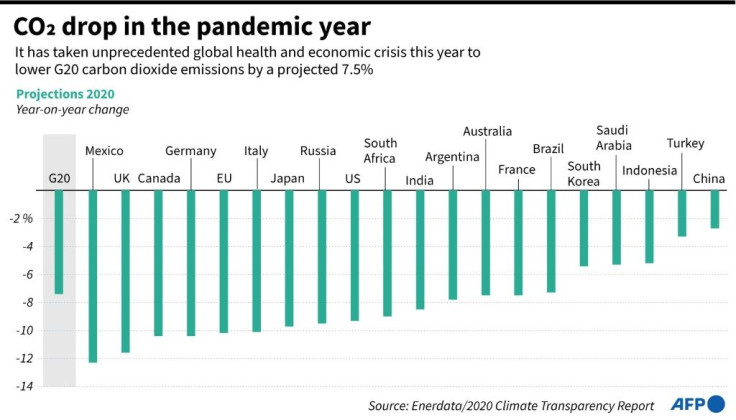

Emissions reductions were most pronounced in the United States (down 12 percent) and the European Union (down 11 percent), the Global Carbon Project said.

In China, however, it said emissions would likely fall in 2020 just 1.7 percent as Beijing superpowered its economic recovery.

By sector, emissions from transport accounted for the largest share of the global decrease, with emissions from car journeys falling by roughly half at the peak of the first Covid-19 wave in April.

By December emissions from road transport had fallen 10 percent year-on-year and emissions from aviation were down 40 percent.

Emissions from industry -- 22 percent of the global total -- were down 30 percent in some countries with the strongest lockdown measures.

The research, normally presented during United Nations climate talks which where delayed this year until 2021 due to the pandemic, said growth in global carbon emissions had started to falter.

Experts warned however that it was too early to say how quickly emissions will rebound in 2021 and beyond.

Long-term emissions trends would be heavily influenced by how countries power their Covid-19 recovery plans, they said.

"All elements are not yet in place for sustained decreases in global emissions, and emissions are slowly edging back to 2019 levels," said Corinne Le Quere, a climatologist at Britain's University of East Anglia.

Under the Paris climate deal, struck among nations five years ago to the day, emissions cuts of around 1 to 2 billion tonnes are needed annually this decade to limit temperature rises to "well below" 2C (3.6 Farenheit).

The UN warned this week that 2020's unprecedented emissions falls would have a "negligible" effect on long-term warming trends without a global switch to green energy.

Philippe Ciais, a researcher at France's Laboratory of Climate and Environment Sciences, said that without the pandemic it is likely that the carbon footprint of big emitters such as China would have continued to grow in 2020.

"It's a temporary respite," he told reporters via video-link.

"The way to mitigate climate change is not to stop activity but rather to speed up the transition to low-carbon energy."

And 2020's emissions fall has not translated into a reduction in the levels of carbon pollution in Earth's atmosphere, Ciais added.

"What we really need to know is if investments linked to economic recoveries are going to create proper growth in low-carbon technologies and a tangible fall in emissions."

Earth's remaining carbon budget is the estimated amount of emissions the atmosphere can take before the Paris climate goals are rendered obsolete.

2020 aside, emissions have grown each year since the landmark 2015 accord, and the UN says they must fall 7.6 percent annually by 2030 to reach the more ambitious Paris temperature cap of 1.5C.

"Put simply, global emissions of carbon (even this year) continue to outstrip nature's ability to lock it up," said Grant Allen, professor of Atmospheric Physics at the University of Manchester, who was not involved in Friday's research.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.