Exelon Corp. (EXC) Nuclear Plant Closures Point To Wider Challenges Facing US Nuclear Sector

Exelon Corp.’s announcement this week that it plans to shutter two Illinois nuclear plants comes at a harrowing time for the U.S. nuclear power sector. Amid fierce competition from cheap natural gas and withering support from state policymakers, utilities are increasingly struggling to keep the aging, hulking power plants in operation.

Chicago-based Exelon (NYSE:EXC), which owns utilities serving Chicago, Philadelphia and Baltimore plus many power plants, said it will close its Clinton plant in mid-2017 and the Quad Cities plant in mid-2018. The nuclear stations lost a combined $800 million in the past seven years, despite being two of the company’s best-performing plants, Exelon said Thursday.

The power company had been waiting on Illinois policymakers to adopt measures to reward nuclear plants and other carbon-free power sources that help the state meet its climate change targets. The legislation included other provisions that would have slapped new charges on consumer energy bills. The policies are entangled in a broader budget war between Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner and House Speaker Michael Madigan, a Chicago Democrat.

Exelon said the measures would have allowed it to find “a sustainable path forward” in an era of plunging electricity prices and rising maintenance costs. After the Illinois Legislature adjourned Tuesday without taking action, Exelon said it was now “forced” to retire the two nuclear plants, the company said in a statement.

However, that decision isn’t necessarily permanent, the Chicago Tribune reported. “The decision can be reversed, but only in narrow circumstances, and as weeks pass a reversal becomes more and more difficult,” Exelon spokesman Paul Adams told the newspaper.

Other utilities — including New Orleans-based Entergy Corp. and Dominion Resources Inc. in Richmond Virginia — had previously announced nuclear closures for financial reasons. Wholesale electricity recently hit a 15-year low, pushed down by the glut of natural gas from the rise in fracking and an overall slowdown in demand for electricity.

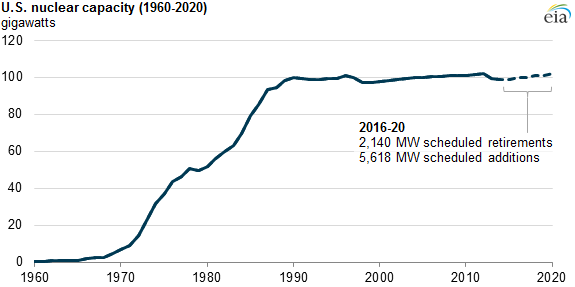

Wholesale prices are likely to remain low in the next few years, which could spell a death sentence for aging plants in need of costly upgrades and lengthy repairs. The majority of the country’s 99 nuclear reactors are more than 30 years old and could operate potentially for as long as 80 years — but only if utilities can afford to keep them running.

Between 15 and 20 nuclear reactors are considered at risk of premature closure within the next five to 10 years, the Nuclear Energy Institute, a trade group, has estimated.

Opponents of nuclear power say that may be a good thing, given the longstanding concerns over radioactive waste disposal and the looming threat of a meltdown, particularly in the wake of the 2011 disaster in Fukushima, Japan. An Associated Press investigation that year found that radioactive tritium has leaked from three-quarters of U.S. nuclear power sites and in some cases contaminated the drinking wells of nearby homes.

Entergy’s Indian Point nuclear plant, which sits just 25 miles north of New York City, has faced a series of mishaps in the last year, including a power failure in the reactor core, an alarm failure and the escape of radiated water into groundwater. Federal officials with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission are now investigating the degradation of critical stainless steel baffle bolts in one of the plant’s nuclear reactors.

“This aging nuclear power plant is becoming increasingly unreliable and puts the welfare of 20 million people at risk every day,” Paul Gallay, president of the citizen group Riverkeeper, which opposes Indian Point, said in a recent opinion piece.

But nuclear power’s supporters say that’s precisely why policymakers and regulators should give utilities the financial support to upgrade and maintain older reactors. Without these plants, proponents argue, the U.S. would lose a critical power source and its largest single source of carbon-free electricity.

Even as utilities install record numbers of wind turbines and solar panels across the country, nuclear plants still provide nearly 60 percent of emissions-free power, followed by hydroelectric plants at around 18 percent, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Unlike renewables, which depend on steady winds and sunbeams to operate, nuclear reactors can produce power on demand and around the clock.

Declining nuclear power could make it harder for the U.S. to reach its climate change goals, U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz, a nuclear physicist, recently said. The Obama administration has committed the U.S. to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by as much as 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. Under the Clean Power Plan, which targets electricity in particular, states must curb carbon emissions from power plants by 32 percent by 2030.

“The idea is we are supposed to be adding zero-carbon sources, not subtracting or simply replacing by building to just kind of tread water,” Moniz said at a May symposium the department organized to discuss the industry’s economic prospects. “I think very few understand that nothing else comes close [to nuclear],” he added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.