Hibernia Networks Bets Speed Of New Fiber Optic Cable Will Win Customers In Crowded North Atlantic Corridor

Two ships will soon meet in the middle of the North Atlantic, each carrying a line of cable that contains a thicket of long glass wires. The ships set sail from New York and London earlier this summer, and crews have been steadily unraveling these two threads from thick spools at the ships’ sterns and letting them fall to the ocean floor ever since. Now, all that’s left is to carefully splice the razor-thin fibers together into single strands contained within the reinforced cable, and light it up.

The builders promise the 2,800-mile cable will offer financial firms the fastest connection between Europe and North America to date when it comes online in September. They expect it to deliver information from one side of the ocean to the other in just under 60 milliseconds, which will be four to five milliseconds faster than their closest competition.

To save those precious milliseconds, the ships that laid the cable took small detours to the north or south to avoid underwater mountain ranges, which ultimately allowed them to shorten the cable's length.

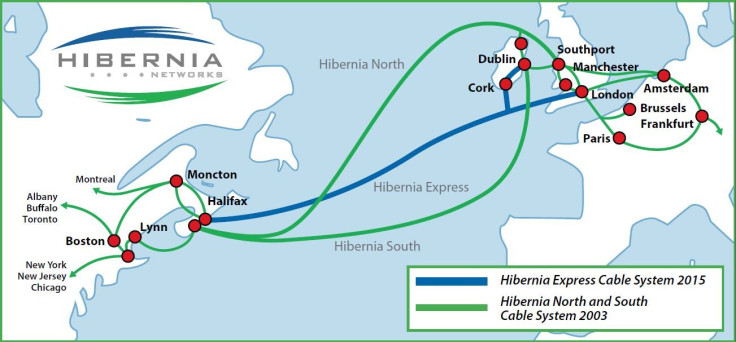

To some, the $300 million investment of the cable’s owner Hibernia Networks is a peculiar wager. Hibernia Express will be the first fiber optic cable installed in the North Atlantic in a dozen years. For over a decade, the world’s major telecom companies have struggled to find enough customers for the fiber optic cables they brought online long ago and shied away from installing new ones.

“It's hard for me to see the need for a new cable,” Andrew Odlyzko, a math professor and longtime internet scholar at University of Minnesota, says.

But Omar Altaji, chief commercial officer of Hibernia Networks, says the company has scrutinized demand along the crowded North American corridor, where it already operates two other cables, and believes that premium speeds and other features of the new project make this cable an exception that violates the rule.

“We saw a need to augment our own capacity but also saw all existing cable systems were reaching saturation points or coming very close to saturation points,” he says. “We made the decision to embark on this because we saw the increase in demand.”

Fiber optic cables transmit information through flashes of light along glass or plastic threads. This light moves much faster than signals carried on traditional copper wires. Together, the world’s 291 in-service fiber optic cables form the backbone of the Internet.

When the World Wide Web publicly debuted in 1991, no one could predict just how much capacity its users would need. At the time, telecom companies guessed that it would be a lot, so they began to install fiber optic cables at a rapid clip. At the height of the frenzy in 2001, $14 billion worth of fiber optic cables came online.

But the world’s Google searches didn’t immediately create enough demand to light up those fibers. And a technology called wavelength-division multiplexing enabled companies to cram more signals onto a single strand of fiber. New cable installations ground to a halt.

One of the places where this slowdown was most obvious was in the North Atlantic, where the dormant Hibernia Express lurks today in the watery depths. Between 1998 and 2003, companies laid 10 fiber optic cables worth $10 billion across the North Atlantic, says Alan Mauldin, research director at the telecommunications research firm TeleGeography. These cables built on a long and ambitious tradition of connecting North America with Europe, which dates all the way back to the first undersea cable installed in 1858, which took 17 hours and 40 minutes to transmit its first message.

But in the dozen years since the Apollo cable came online in 2003, not a single new cable was installed. And even those that were already in place did not operate at maximum capacity. Today, only about 20 percent of the potential capacity between New York and London is in use, according to Mauldin.

Altaji at Hibernia Networks is acutely aware of this shift. “The days of ‘build it, and they will come’ are no longer here,” he says.

But that hasn’t deterred Hibernia Networks, whose leaders believe that the speed of their latest connection will win contracts from a small but lucrative group of financial trading firms. Demand for faster transfer of information between the major financial centers of New York, London, Frankfurt and Chicago have driven telecom companies to install ultra-fast connections in recent years which may not have otherwise been feasible.

“To me, building general purpose internet connectivity across the North Atlantic along the route that Hibernia has selected is very questionable,” Odlyzko at University of Minnesota says. “For the financial industry, I can see saving a few milliseconds might potentially be worth it, but I think that's the only justification I can see.”

Since Hibernia Express will serve such a specialized customer base, its debut does not necessarily mean that new cables will begin to pop up at the frequency of the early 2000s. Overall, the growth of the Internet has begun to slow -- despite the rising popularity of video, which now makes up about 64 percent of Internet traffic.

At the height of the Internet’s growth, the web was expanding by as much as 1,000 percent a year. But total internet traffic rises at a much slower pace these days, from 31 percent in 2012 to 21 percent in 2014, according to the latest Internet report by Mary Meeker of the venture capital firm Kleiner, Perkins Caulfield and Buers.

“Internet traffic is growing, but it's growth rate is slowing down, and it's actually slowing down quite substantially,” Odlyzko says. “I don't think you really need new cables across the Atlantic to handle the volume of traffic.”

Instead of building en masse, telecom companies have lately placed careful bets on cables that will serve new areas or a lucrative client group. For example, demand has grown in Asia and Africa over the past three years, and more than $1 billion of new cables are currently slated to come online in Latin America and between Asia and Europe by 2016.

Today, Mauldin estimates that between $1 and $3 billion worth of cables come online each year around the world, which is far from the record-setting $14 billion in 2001. There are currently more than 30 planned cables around the world.

He also points out that eventually, the cables installed during the rush of the early 2000s will need to be replaced. Since most of those original cables were built on technology with a 25-year lifespan, the next big wave of cable installations may be just over the horizon.

“I think the industry is still ticking,” Mauldin says. “There's still demand for new cables.”

Hibernia Networks plans to hedge its bets slightly by not relying solely on customers from major financial firms. On Monday, Hibernia Networks announced that a spinoff of the main cable had hit the shore of Cork, Ireland. Hibernia Express will bring faster access for major content producers that have recently opened data centers there, such as Microsoft, Apple and Google.

In May, Hibernia Networks announced that Microsoft had already signed on as a customer. On Wednesday, Hibernia Networks issued a press release inviting other potential clients with major data centers in Ireland to come aboard.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.