How To Sleep Better? Go Camping; Deprivation Affects Memory Formation, Learning

All of us sleep, and yet, sleeping is still a largely mysterious phenomenon that philosophers of old and scientists in modern times have tried to understand. It has been compared to death in the Bible in times past, in contrast to which science has shown the amount of energy used by the body during sleep is not much lower than in waking hours.

We feel physically rested after a good night’s sleep, and are often irritable in the morning if we slept badly. The immune system is also strengthened when we sleep. But what else is sleep actually needed for?

Two separate studies, both published Friday in the journal Science, examined mice brains and how they function during sleep. And they both found that the brain recalibrates and resets itself while we are in the land of dreams, so it can be prepared to learn new things and form new memories the next day.

Researchers from John Hopkins University in Baltimore published a summary of their findings in the journal under the title “Homer1a drives homeostatic scaling-down of excitatory synapses during sleep.” In it, they said the synapses in the brain (they are the structures that connect neurons, allowing them to transmit information between themselves) recalibrate themselves during sleep so that the mice could retain information they learnt during their waking hours for later use.

They also found that it is not just sleep deprivation and other sleeping disorders that interfere with the process of recalibration, but that sleeping pills to get a sound sleep can have a similar effect.

Graham Diering, a postdoctoral fellow at John Hopkins who led the study, said in a statement: “Our findings solidly advance the idea that the mouse and presumably the human brain can only store so much information before it needs to recalibrate. Without sleep and the recalibration that goes on during sleep, memories are in danger of being lost.”

The researchers also identified important molecules that govern the process of recalibration of the brain cells.

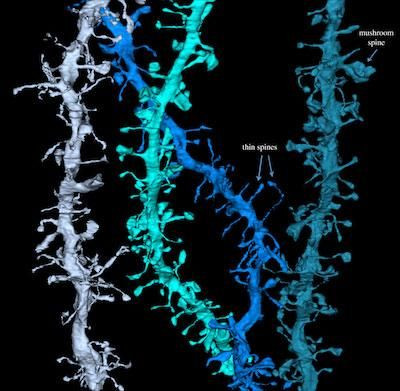

Another study by scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW) and the University of California-San Diego looked at the size of synapses, and how they change during sleeping and waking hours. Using a method called serial scanning 3D electron microscopy, the four-year study looked at two areas of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mice.

They found that synapses shrink about 20 percent when the mice had a few hours of sleep. They cited this as proof of the synaptic homeostasis hypothesis, which says sleep is the price animals pay to keep learning new things.

Synapses grow when we are awake, becoming stronger and more effective, and shrink and become weaker when we sleep. This is necessary in order to not overburden the brain, according to the hypothesis.

“This shows, in unequivocal ultrastructural terms, that the balance of synaptic size and strength is upset by wake and restored by sleep. It is remarkable that the vast majority of synapses in the cortex undergo such a large change in size over just a few hours of wake and sleep,” Chiara Cirelli of UW said in a statement.

The study was published under the title “Ultrastructural evidence for synaptic scaling across the wake/sleep cycle.”

So what do you do if you are an insomniac, or affected by one of the many sleeping disorders that plague our species? Well, research suggests a solution to that too: go camping.

The leading causes for sleep troubles is the lack of natural light during the day and perfect darkness during the night, scientists from the University of Colorado, Boulder, studied the circadian rhythms of campers in the Colorado wilderness. Specifically, they measured their levels of melatonin, a hormone responsible for promoting sleep and preparing the body physiologically for nighttime, and compared it with melatonin levels with volunteers who stayed in their urban homes.

They found that even a weekend away from city lights brought forward the rise in melatonin levels by 1.4 hours in the summer, and by 2.6 hours in the winter. With no artificial lights to hamper the body’s natural circadian rhythm, it was better aligned with the seasons, which is how it works with many animals.

“These studies suggest that our internal clock responds strongly and quite rapidly to the natural light-dark cycle. Living in our modern environments can significantly delay our circadian timing and late circadian timing is associated with many health consequences. But as little as a weekend camping trip can reset it,” Kenneth Wright, integrative physiology professor at the university and lead author of a paper on the subject, said in a statement.

The paper, titled “Circadian Entrainment to the Natural Light-Dark Cycle across Seasons and the Weekend,” was based on two studies (one from the summer and the other from winter), was published Wednesday in the journal Current Biology.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.